Literature Search and Terms

Shaman in America

A literature search was conducted using the

following databases: CINAHL PubMed, and

Google using the following terms; culture, culture

shock, cultural competence, culture and

healthcare, South East Asian and culture, Hmong

and culture, Mien and culture, culture and

disparities, and shaman. Several selected articles

are discussed and the following terms are

provided as important concepts that are related to

our topic on the South East Asian culture.

Culture

Culture is defined as the totality of socially

transmitted behavioral patterns, beliefs, values,

customs, lifeway, arts, and all other products of

human work and thought characteristics of a

population of people that guide their world view

and decision-making (Prunell, 2009, p. 1).

Culture Shock

Culture shock refers to feelings of

bewilderment, confusion, disorganization,

frustration, and stupidity, and the inability to

adapt to the differences in language and word

meaning, activities, time, and customs, that are a

part of the new culture (Murray, Zentner &

Yakimo, 2009 p. 135).

Cultural Competence

Cultural competence is the ability of the health

care provider, agency, or system to acknowledge

the importance of culture on all levels (client,

provider, administration, and policy) for

incorporation into health care (Murray et al., 2009

p. 140).

Conceptual Framework

The Roy Adaption Model (RAM) has been selected to

guide our presentation. The RAM views the individual

as a adaptive system in constant interaction with an

internal and external environment. The environment

exposes the individual to a variety of stimuli that

threaten or promote one’s unique wholeness

(Alligood, 2010, p. 310). For example, healthcare

professionals that take the opportunity to consider

there own, as well as their patients’, cultural beliefs,

practices and communication styles can positively

impact their patients’ ability to adapt.

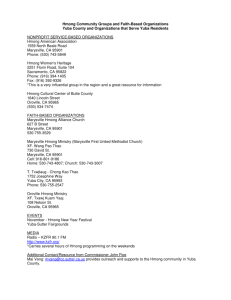

Background:

South East Asians Uprooted to America

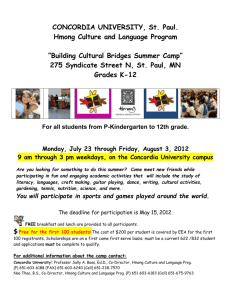

In the early 1980’s the Hmong and Mien

began to immigrate to the United States with

preferred refugee status after the Vietnam war

where they fought along side the CIA blocking

arms importation into Vietnam . Many of the

older adults, who fled Laos after the war, lived

much of their lives in refugee camps in Thailand

separated from their community and social

supports (Cobb, 2010) .

Although they brought with them their

language, social structure, customs, religious

and health beliefs, young and old, arrived in

the United States where the culture, language

and socioeconomics were very different (Cobb,

2010) . One could easily conclude the myth that

adversity came to a miraculous end once

refugees of the South East Asian conflict

arrived in the United States. However, the sense

of loneliness, loss, and shame became

magnified amongst refugees relocated to the

United States (Sheng-Mei Ma, 2005).

Hmong shown here playing the Qeej , a

bamboo pipe instrument known worldwide as the

cultural identifier for Hmong people. Hundreds of

years old, it plays a pivotal role at Hmong

funerals, as the sound of its chords are thought by

Hmong to call the soul out of the body and into

the afterworld.

In keeping with Roy’s Adaption

Model we will explore cultural

disparities and venture into a

variety of South East Asian

cultures to gain understanding of

the population that entered the

“great American melting pot” with

a unique story. The culture shock

that is often experienced by

immigrants entering the United

States will be analyzed with the

focus on the elderly population.

Cultural barriers that exist in

providing care to Mien and Hmong

Americans will be reviewed, and

strategies to provide cultural

competent care specific to this

population will be shared.

The Big Transition

As the Southeast Asians entered the United States,

they entered a world that was starkly different from their

previous home. They lived in mountainous areas and were

an agrarian society (Prunell, 2009).

Both Mien and Hmong have experienced a series of

traumatic events: the war in Laos, the Pathet Lao takeover

and subsequent Hmong persecution (including the threat

of genocide), the harrowing nighttime escapes through

jungles and across the Mekong River, the hardships of

refugee camps in Thailand, and finally resettlement in the

United States, with not only housing, income, language,

and employment concerns, but also the separation of

families and clans, inability to practice traditional religion,

hasty conversion to Christianity, and the breakdown of the

gender hierarchy, among many others (Sheng-mei Ma,

2005).

Many lacked formal education; were predominantly

illiterate, lived in primitive circumstances, and had no

contact with the modern world. One journalist has

facetiously characterized Hmong refugees’ transition from

Southeast Asia to the West as moving "from the Stone Age

to the Space Age“(Sheng-mei Ma, 2005).

Acclimating to

America

The documentary movie “The Split Horn”

depicts a Hmong shaman, Paja Thao, as he

struggles to maintain ancient traditions while

his children embrace the American culture.

Paja sees his children adapting to American

society more willingly than his generation.

His children are learning the English

language, achieving an education, and

marrying Americans outside their culture.

Paja’s children talk about the guilt and

distress of living in two worlds. They enjoy

the America they have come to know while

attempting to please older generations by

honoring the culture and tradition of the

homeland (Taggart, 2001).

Cause and Effect Conceptual Inventory on Cultural Shock

Causes

Language and

Word

Meaning

Differences

Differences in

Cultural

Practices

Differences in

Health

Practices

Differences in

Social

Structure

Culture Shock

Loneliness

Depression

Confusion

Isolation

Frustration

Effects

Virginia Carrier-Kohlman, V., Lindsey, A.M., West, C., (2003)

Phases of Culture

Shock

Unpleasant feelings often associated with culture shock

occur in stages and can be magnified when one moves to a

culture that is very different from their own. Brink and

Sanders, as cited by, Murray et al., 2009, describe four

phases associated with culture shock.

Honeymoon phase: This stage is characterized by

excitement, exploration, and pleasure. This phase may be

experienced by a short-term visitor to a new area, by a

geographic move to a different location, or during initial

employment in a different health care area.

Disenchanted phase: Person feels stuck, depressed,

irritated, and that the environment is unpredictable and no

longer exotic. The normal cues for social intercourse are

absent and the person is cut adrift. The person may become

physically ill.

Beginning resolution phase: New cultural behavior patterns

are adopted. Friends are found. Life becomes easier and

more predictable.

Effective function phase: The person has become almost

bicultural and may experience reverse culture shock on

return home after living abroad or when transferring to a

different health care agency.

(Murray, et al., 2009, p.135-136).

Shaman

Societal Perfectives on the Elderly South East Asians

Cultural implication of the southeast Asian culture, ethnicity, and socioeconomic level

influence the role of the older adult in family relationships and determine health practices.

Elderly Southeast Asians often state the most stressful of all adaptations to the American

culture is “role loss” which may be the most corrosive to the ego. Southeast elderly Asians who

were well respected and held jobs of honor such as colonels and military communications

specialist are now janitors and chicken processors. Many southeast Asians state, “We have

become children in this country” ( Fadiman, 1997, p. 206).

In addition, Southeast elderly Asians feel that their children have assumed some of the power

that once to belong to them. The elders have taken this especially hard as the their identity has

always hinged on tradition. “We have lost all control. Our children do not respect us. One of the

hardest things for me is when I tell my children things and they say, “I already know that”

(Fadiman, 1997, p. 207).

Although the Hmong elders state Americanization may bring certain benefits such as job

opportunities, more money and less cultural dislocation; Hmong parents are likely to view any

earmarks of assimilation as an insult and a threat ( Fadiman, 1997, p. 207).

Religious Beliefs and Healthcare

Traditional Hmong believe in animism, the belief in the spirit world and it’s link to all

living things. They believe that illness can be the effect of physical and spiritual factors.

Hmong believe in order to maintain good health a balance between the body and the spirit

must be maintained. They also believe if their ancestors are offended illness or disease

may ensue.

A phenomenon called Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome (SUNDS)

which in the 1970s and 80s mysteriously struck Hmong and other Southeast Asian male

refugees in their sleep. Some survivors claimed the attack of a Kingstonian "Sitting Ghost"

(The Woman Warrior 81) on their chests, pressing air out of their lungs. Western doctors

could do no more than attributing the cases to cardiac arrest in otherwise perfectly healthy

men, a great number of whom reported depression

and ill-adjustment to the U.S. (Munger, 1987).

Health conditions common to Hmong include depression, anxiety, suicide and

post traumatic stress disorder. As a result

of experiences during the Vietnamese war,

there flight to safety and culture stressors

many Hmong continue to have nightmares

and flashbacks related to the terrors they

experienced in Laos. Unemployment and

reversal of family roles have created

additional cultural stressors.

This You Tube video illustrated the culture shock encountered by Hmong males

and the stress they encounter while attempting to adapt to American life.

South East Asian

Culture and Healthcare

The diversity of the United States population

has resulted in the “great American melting

pot”, which has brought about a need for

culturally competent healthcare. Because

culture has a powerful influence on health and

illness, health-care providers must recognize,

respect, and integrate patients’ cultural beliefs

in their practice (Prunell, 2009 p.1).

Literature suggests that disparities in

healthcare among ethnic, social, and

economic groups show that healthcare

providers need to be attentive to cultural

diversity. In a 2010 study, several barriers to

providing healthcare to Hmong were

enumerated. This study revealed barriers that

resulted in misunderstanding and

misinterpretation between the healthcare

provider and South East Asian Americans

stemmed from differences in language,

religion, culture and social organizations

(Cobb, 2010, p. 82).

Research Bridging Cultural Barriers

In 2008 study, joint endeavors between researchers and the Hmong community

came together to develop and test the quality of a hypertension care survey

instrument. In-depth interviews were undertaken with Hmong community leaders

and hypertensive patients to enrich the understanding of quality of care from the

Hmong socio-cultural perspective. The goal of this study was to develop a quality care

survey that would assist in yielding information to help provide culturally appropriate

care to the Hmong American population. The collaborative effort at all levels within

the community helped researchers and the community members to test survey

instruments that was more culturally, linguistically, and socially appropriate. In

addition this study, provided the means through which the Hmong population could

voice their own health care needs that could be used in future research (Wong,

Mouanoutoua, Chen, 2008).

In the book titled, “The Challenge of Cross-Cultural Competency in Social Work “,

written by Dr. Jean Schuldberg , a study conducted in 1993 refers to the

recommendations of the participants of the research study concluding that, “when

teaching cultural competency it is important for the teachers to name the injustices

the Southeast Asians experienced and highlight our rapidly changing global

community” (Schuldberg, 2005).

Cause and Effect Inventory for Cultural Competence

Cause

Overcome Language Barriers

Use of Interpreter

Cultural Awareness

Integrations of Cultural

Practices

Cultural

Competence

Establishment of Support

System

Reversal of Culture

Shock Symptoms

New Cultural Behavior

Patterns Adopted

Effect

Carrier-Kohlman et al. (2003)

Cultural Competent Care

•

Cultural competent healthcare practices include the consideration of others tradition,

magicoreligious or biomedical beliefs and practices, individual responsibility for health,

self-medicating practices and views on mental illness.

•

Hmong may seek westernized medical care, traditional healers or Shamans who

perform rituals for healing. They may seek herbalists and take multiple treatments for

the same condition. Some practice home remedies such as coining or cupping. Health

care workers should not confuse the patterns of coining or cupping for abuse.

•

Bruising may be seen along with coining and pricking the center of the bruise may be

done to release bad spirits; unsterilized sewing needles are generally used for this

purpose. Healthcare workers should always encourage education regarding the use of

sterilization of needles (Prunell, 2009, p. 213-214).

Cultural Competent Care Continued

•

Parents may tie strings around baby’s necks and older children and adults

may have strings tied around wrists, waists, or ankles

•

Necklaces and strings must remain on until they fall off naturally, removing

them too soon may result in soul loss

•

Healthcare worker should never remove strings, necklaces, or bracelets

without the parents’ or patient’s permission

•

Some Southeast Asians utilize herbs prescribed by a herbalist Studies have

indicated that these herbs may have pharmaceutical properties. Healthcare

workers must always ask patients about their use of herbs

(Prunell, 2009, p. 213-214)

Mey Chao-Lee

Mey Chao-Lee is a cultural competency coordinator for the

Shasta County Health and Human Services Agency. Mey ChaoLee fled Laos with her family as a young girl and later

immigrated to America. Recently she became the first Mien to

earn a master’s degree in social work from Chico State

University, and has dedicated her life to helping those who

share her culture. We are honored to have her here with us

today to learn more about her journey to America and her

Mein culture.

Video with Mey can be viewed on first power point submitted

using the instructions provided.

Sophia Questions

• If you were to be uprooted from America to

Laos what health practices would you want

to hold on to and why?

• Would you ask for a traditional American

doctor to treat you or would you be willing to

have a Shaman treat you?

• Would you be willing to take the South East

Asian traditional medications and

treatments?

• What could Shamans do to gain your trust?

• What do you think could help break through

the language barrier?

• Would you want to practice your religious

beliefs?

References

Alligood, M. R. (2010). Nursing Theory: Utilization & Application (4 ed.). Maryland Heights,

Missouri: Mosby Elsevier.1

Carrier-Kohlman, V., Lindsey, A. M., & West, C.M. (2003). Pathophysiological phenomena in

nursing: human responses to illness (3 ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier.

Cobb, T. (2010). Strategies for providing cultural competent health care for Hmong Americans.

Journal of Cultural Diversity, 17(3), 79-83. Retrieved February 10, 2011 from CINAHL

Fadiman, A. (1997). The spirit catches you and you fall down. New York, New York: Farrar,

Straus & Giroux.

Munger, R. (1987). Sudden death in sleep of Laotian-Hmong refugees in Thailand: A casecontrol study. American Journal of Public Health, 77, 1187-1190.

Murray, R. B., Proctor-Zentner, J., & Yakimo, R. (2009). Health promotions strategies through

the life span (8 ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Prunell, L. D. (2009). Guide to culturally competent health care (2 ed.). Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania: F.A. Davis Company.

Regan, K. (2009, November). Uniting cultures: May Chao-Lee culture competency coordinator.

Enjoy Magazine, 53-56.

Schuldberg, J. (2005). The challenge of cross-cultural competency in social work. New York,

New York: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Sheng-Mei, M. (2005). Hmong Refugee Death Fugue. Hmong Studies Journal, 6, 1-36.

Sudden Death Syndrome (2008), Retrieved February 8, 2011, from

http://www:youtube.com/with?v=8rAn2Tjlv4

Taggart, S. (2001). Split horn of a Hmong shaman in America [Motion Picture]. United States

Vimeo Mae Interview (2011), Retrieved February 8, 2011, from

http://.vimeo.com/20350433

Wong, C., Mouanoutoua, V., & Chen, M-J (2008). Engaging community in the quality of

hypertension care project with Hmong Americans. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 15(1),

30-36.