Early Years of the New Government, 1789

advertisement

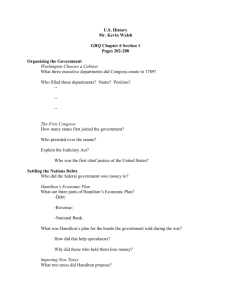

Early Years of the New Government, 1789-1800 Launching the New Ship of State Washington for President Washington was unanimously elected as president by the Electoral College in 1789. He is the only president elected unanimously in our nation’s history. He was also probably the only candidate who did not angle for the office. He commanded his followers by strength of character rather than by politics. Washington’s journey from Mt. Vernon to New York City (the capital) took many days. Not because the distance was great but rather because Washington did not wish to appear too eager to assume office and power. He took the oath of office on April 30, 1789. Washington For President Washington put his stamp on the presidency and the government quickly by establishing the cabinet. The Constitution does not mention a cabinet but the system it put in place for the president to deal with the heads of the departments of the executive branch was cumbersome. The first three cabinet positions were Secretary of State (Jefferson) Secretary of the Treasury (Hamilton) and Secretary of War (Henry Knox). Shortly after these, the Attorney General was added to the cabinet also in 1789. The Bill of Rights The first issue to face the first Congress in 1789 was the drafting of the Bill of Rights to amend the Constitution. James Madison drafted the amendments and skillfully guided them through Congress. These first ten amendments were ratified by the states in 1791. The first Congress also created effective federal courts under the Judiciary Act of 1789. The act organized the Supreme Court, with a chief justice and five associate justices as well as federal district and circuit courts and established the office of attorney general. John Jay became the first chief justice of the Supreme Court. Hamilton and Public Credit The key figure in the new government was Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was a genius and regarded himself as a kind of prime minister in Washington’s cabinet and often got into the affairs of other departments, including Jefferson’s State Department. Hamilton set out immediately to fix the economic problems that had crippled the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton’s plan was to shape fiscal policies that would favor the wealthier groups. They in turn would gratefully lend the new government monetary and political support. Then the new government would thrive and the prosperity would trickle down to the masses. Hamilton and Public Credit Hamilton boldly urged the Congress to fund the entire national debt “at par” and to assume completely the debts incurred by the states during the Rev. War. Funding at par meant that the federal government would pay off its debts at face value, plus accumulated interest totaling more than $54 million. Foremost in Hamilton’s thinking was the belief that assumption would chain the states more tightly to the federal government. Hamilton’s plan would move wealthy creditors from the states to the federal government. States with heavy debts like Massachusetts loved Hamilton’s plan. States with small debts like Virginia were less enthused. Virginia did not want the state debts assumed but it did want the new federal district (new capitol), the District of Columbia, to be located on the Potomac River. If this happened,Virginia would gain in commerce and prestige. Hamilton persuaded Jefferson to line up enough votes to pass his plan through Congress and in return the District of Columbia would be built on the Potomac. The bargain passed in 1790. Customs Duties and Excise Taxes The national debt quickly swelled to $75 million but Hamilton was not greatly worried. He reasoned that the more creditors to whom the government owed money, the more people there would be with a personal stake in the success of his ambitious enterprise. The money to pay the interest on the debt and run the government was to come from two main sources. The first was customs duties (import taxes) derived from a tariff. Tariff revenues, in turn, depended on a vigorous foreign trade. The second source of income for the government would come from an excise tax (sales tax) on a few domestic products, most notably whiskey. This tax on whiskey was seven cents a gallon. In the backcountry, whiskey was so available that it served as money in many places. Hamilton and the Bank of the United States The cap to Hamilton’s program was a proposed Bank of the United States. He modeled this bank on the Bank of England. He said that the government would be the major stockholder and that the bank would provide a place for the federal government to deposit its surplus monies. The bank would also print badly needed paper currency and thus provide a stable and sound national currency. The biggest question about the bank was its constitutionality. Jefferson argued strongly against the bank. He insisted that there was no specific authorization in the Constitution for a national bank. He was convinced that all powers not specifically granted to the federal government were reserved to the states. Jefferson believed that the Constitution should be interpreted “literally” or “strictly.”(Letter of the law) Hamilton and the Bank of the United States Hamilton believed that what the Constitution did not forbid it permitted (spirit of the law); Jefferson believed that what it did not permit it forbade. Hamilton invoked the clause in the Constitution that says Congress may pass any laws “necessary and proper” to carry out the business of government (Art. I section VIII). In short, Hamilton contended for a “loose” or “broad” interpretation of the Constitution. Hamilton’s views were persuasive and Washington signed the measure into law, creating the Bank of the United States in 1791. The bank was chartered for 20 years and was to be located in Philadelphia. The Whiskey Rebellion The Whiskey Rebellion broke out in western Pennsylvania in 1794 and was the first real test of the new federal government. Hamilton’s excise tax was considered by the farmers of this area as huge burden on an economic necessity and a medium of exchange. Defiant distillers raised the cry “Liberty and No Excise” and boldly tarred and feathered tax collectors bringing collections to a halt. The Whiskey Rebellion President Washington was alarmed by the events in Pennsylvania. With the encouragement of Hamilton, he summoned the militia of several states nearly 13,000 troops in total, and led the troops up to Pennsylvania. When the troops reached the area they found no insurrection. The distillers were overawed, dispersed, or captured quickly. Only three rebels were killed. Washington later pardoned the two people who were convicted in connection with the rebellion. The consequences of the Whiskey Rebellion were huge. It showed that the new federal government was strong and stable. Emergence of Political Parties National political parties as we know them today were unknown when Washington became president. The Founders at Philadelphia had not envisioned the existence of permanent political parties. Organized opposition to the government seemed tainted with disloyalty. When Jefferson and Madison first organized their Democratic - Republican Party opposing the Hamiltonian program, they confined their activities to Congress and did not anticipate creating a long-lived and popular party. The twoparty system has existed in the U.S. since that time. Their competition for power has proved to be an indispensable ingredient of a sound democracy. The party out of power plays the role of the balancing the government and ensuring that politics never drift too far away from the wishes of the people. Washington’s Neutrality The alliance that we had with France during the Revolutionary War stated that the alliance was to last “forever.” The French revolution had the potential to drag the young United States into a war that we did not want to be in. Britain was sure to exploit this time of French weakness and seize territories around the globe. Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans were in favor of honoring the alliance. They argued that America owed France its freedom and that now was the time to pay the debt. President Washington was not swayed by the Jeffersonian argument. He believed that war was to be awarded at all costs. He knew that the U.S. in 1793 was militarily weak, economically unstable, and politically disunited. Washington knew that solid foundations were being laid and that given enough time our population would be large enough and powerful enough to assert our rights and strength with success. Washington’s Neutrality Washington issued his Neutrality Proclamation in 1793, shortly after the outbreak of the feared war between Britain and France. The document not only proclaimed neutrality but warned American citizens to be impartial as well. This neutrality proclamation would prove to be a major justification for later isolationist policies of the U.S. government. Our neutrality policy was sorely tested by the British. For ten years they had been retaining a chain of northern frontier posts on U.S. soil in defiance of the Treaty of 1783. Britain was reluctant to give up the profitable fur trade in the Great Lakes region and also hoped to build up an Indian buffer state to contain America. British agents openly sold firearms and alcohol to the Indians of the Miami Confederacy, eight Indian nations who terrorized Americans invading their lands. Washington’s Neutrality In 1794, an American army commanded by “Mad Anthony” Wayne routed the Miami’s at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The British refused to shelter Indians fleeing from the battle and the Confederacy quickly agreed to terms of surrender with Wayne. The Treaty of Grenville (1795) the confederacy gave up large amounts of land in the Old Northwest, including most of Indiana and Ohio. Foreign Treaties and Washington’s Farewell In 1794, Washington decided to send Chief Justice John Jay to England to try to avert war. Jay won few concessions from the British. They did agree to evacuate the chain of military posts on U.S. soil and to pay damages for the recent seizures of American ships. They forced Jay to agree that the United States would pay all the debts still owed to British merchants on pre-revolutionary accounts. When word of Jay’s Treaty reached the United States, it became very unpopular. Jay’s Treaty did have some unforeseen consequences. Spain feared that this new treaty signaled the beginning of a new alliance between the U.S. and Great Britain and hastily agreed to a treaty with the U.S. Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795 granted the U.S. free navigation of the Mississippi as well as control of disputed land north of Florida. President Washington decided not to seek a third term in 1796 and retire from public life. In his Farewell Address to the nation in 1796, Washington strongly advised the avoidance of “permanent alliances.” Washington favored temporary alliances for “extraordinary emergencies.” John Adams for President After Washington’s retirement, the Federalists turned to Washington’s vice president John Adams to be their candidate for president. The Democratic-Republicans turned to Thomas Jefferson as their candidate. The campaign was heated and dirty. Cultured Federalists referred to their opponents as “fire-eating salamanders, poisonsucking toads.” As for the issues of the campaign, Jeffersonian assailed the crushing of the Whiskey Rebellion and the hated Jay’s Treaty while the Federalists supported them. Adams won by a narrow margin of 71 votes to 68 in the Electoral College. By coming in second, Jefferson became Adams’ vice president (changed by the 12th amendment in 1804). Adams was one of the ablest statesmen of his day. Adams impressed observers as a man of tough principles and stubborn devotion. He was also tactless and prickly. His biggest problem was that he had to step into Washington’s huge shoes which would never fit anyone. XYZ Affair and Unofficial Fighting with France The French were infuriated by Jay’s Treaty with England. They, like Spain, saw it as leading to an alliance with Great Britain and as a violation of the treaty of 1778. French warships began to seize defenseless American merchant vessels totaling 300 by mid1797. The French also refused to receive America’s newly appointed ambassador even threatening to arrest him. President Adams tried to reach an agreement with the French by appointing three men to try to negotiate again. The men hoped to meet with the French foreign minister but were secretly approached by three go-betweens, later referred to as X, Y, and Z in correspondence back to the U.S. These men demanded a loan for France of 32 million Francs and a bribe of $250,000 for the privilege of talking with the French foreign minister. XYZ Affair and Unofficial Fighting with France These terms were not acceptable to the envoys and negotiations quickly broke down. When word of the X,Y, and Z Affair reached the U. S. many citizens screamed for war with France. War preparations moved along at a feverish pace. The Navy Department was created and the three ship navy was expanded and the Marine Corps was reestablished. The fighting was confined to the seas and in two and a half years of undeclared war, U.S. forces captured over 80 French vessels though several hundred merchant vessels were lost to the French. The fighting ended in 1800 thanks in part to Napoleon Bonaparte seizing control of France and being eager to end the fighting with America so he could continue with conquering Europe without distractions. The Alien and Sedition Acts The Federalist Party capitalized on the anti-French sentiment to push through Congress in 1798 a set of laws aimed at minimizing their Jeffersonian foes. The first of these laws were aimed at supposedly pro-Jeffersonian “aliens.” Most European immigrants who lacked wealth were scorned by the Federalist Party and welcomed by the more democratic Jeffersonian. This first Alien Act raised the residence requirements for aliens (immigrants) who wanted to become citizens from five years to 14 years. Two later Alien Acts empowered the president to deport dangerous foreigners in time of peace and to deport or imprison them in time of hostilities. The Sedition Act said that anyone who impeded the policies of the government or falsely defamed its officials, including the president, would be given a large fine and imprisoned. This last act was a direct challenge to freedom of the press and freedom of speech. The Alien and Sedition Acts Many Jeffersonian editors were indicted under the Sedition Act. Ten were brought to trial and convicted, often by Federalist packed juries. The Sedition Act seemed to be in direct conflict with the Constitution but the Federalist dominated Supreme Court had no intention of striking down a Federalist law. The Federalists intentionally wrote the law to expire in 1801 so that it could not be used against them in the election. It did, however, win many converts for the Jeffersonian. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions Jeffersonian refused to accept the Alien and Sedition Laws. Jefferson himself feared that Federalists might even try to wipe out other precious Constitutional guarantees. Jefferson secretly authored a series of resolutions which the Kentucky legislature passed in 1798 and 1799. James Madison wrote a similar statement that was passed by the Virginia legislature in 1798. In their resolutions, both men stressed the compact theory. This meant that in creating the federal government, the 13 sovereign states had entered into a “compact” or contract regarding its jurisdiction. The national government was consequently the agent or creation of the states. They further argued that since the states created the federal government, the states should also have the final say on the constitutionality of the laws passed by the federal government. If the laws were not constitutional or if the federal government had overstepped its authority, the states could nullify or refuse to accept the laws passed by the federal government. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions Many Federalists argued that it was the people, not the states, who had made the original compact and that it was the Supreme Court, not the states, that determined constitutionality questions. The Virginia and Kentucky resolutions were a brilliant formulation of the extreme states rights view regarding the Union. They were later used by southerners to support nullification and ultimately secession. Neither Jefferson nor Madison had any intention of their theory being used to break up the Union.