Why the ICGG is critical

advertisement

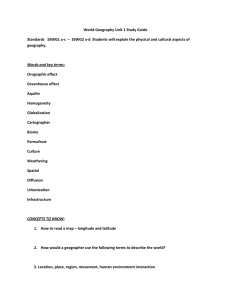

Radical school geography: retrospect and prospect 1983 2023 2003 Geographical Education will help practicing teachers take a critical look at geography in secondary schools. After an account of recent curriculum change, it introduces the emerging humanistic and radical forms of geographical education which, it is argued, will allow geography teachers to make a constructive contribution to human development and social justice. Chapter 3 Behavioural geography Chapter 4 Humanistic geography Chapter 5 Geography through art Chapter 6 Welfare approaches to geography Chapter 7 Radical geography Chapter 8 Political education Chapter 9 Development education Chapter 10 Environmental education Chapter 11 Urban Studies Three steps in my argument: • a look back at developments in geography, education and school geography over the past 20 years; • an assessment of what these developments now offer school geography in relation to teaching and learning about space, place and nature; and • an illustration of how this potential might be realised within KS3 curriculum units. Forms of school geography and ideological traditions • Geography as skills • Geography as cultural heritage • Geography as personal growth • Geography as critical literacy • Utilitarian/informational • Cultural restorationism • Liberal humanist (classical humanist) • Progressive (child centred) • Reconstructionist (radical) • Vocationalist (industrial trainer) Morgan, 2002 Rawling, 2001 Radical school geography: an initial orientation School geography as critical literacy is assertive, class-conscious and political in content. Social issues are addressed head on. The stance is oppositional, collective aspirations and criticisms become the basis for action. Pupils are taught how to read and write the world. After John Morgan, 2002, 56 Urgent questions . . geographical responses For the questions that radical geography was founded to confront are present still in mutated, far more powerful and dangerous, social and cultural forms . . . the terrible injuries visited still on the world's most vulnerable peoples, the formation of global structures far beyond human control, the transformation of material into virtual reality, and the consequence of all these and more in the massive destruction of nature Richard Peet, 1999 Some of the biggest and most pressing issues of our era are, not solely but none the less absolutely inherently geographical. Whether it be globalization, the rapidly shifting mappings between society and place, or the relationship between society and nature. Space, place and nature. Each of them is at the heart of major questions of our time and each of them is in need of, and indeed is in the process of, being reimagined. Doreen Massey, 2001 Geography at Key Stage 3 However, there continues to be more unsatisfactory teaching in geography than in most other subjects. OFSTED, 2001/2 • narrow range of teaching approaches • over-reliance on a single text book or photocopied worksheets • teachers’ low expectations • recording rather than applying information • lack of differentiation • teaching that is competent but ‘largely cheerless’ From radical to critical geography Richard Peet on the development of radical geography 1. Rediscovery of classics of Marxism. A phase of rediscovery. 2. Movement through structuralism, structuration and realism to emerge in more diverse forms such as regulation theory. A phase of breakdown in political solidarity. 3. Entry of poststructural and postmodern philosophies and a more deeply theorized feminism. Some Marxist geographers appropriate and synthesise the new ideas. A phase of eclecticism and antagonisms. 4. Consolidation of realistic and profound theories, rooted in the material and able to confront cultural technologies that incorporate resistance. A phase of reconciliation and mutual respect Critical human geography Critical human geography is now a diverse set of ideas and practices linked by a ‘shared commitment to emancipatory politics within and beyond the discipline, to the promotion of progressive social change and to the development of a broad range of critical theories and their application in geographical research and political (Johnston, Gregory and Smith, 1994, 126). It is characterised by internal specialization and philosophical pluralism and includes geographies of gender, disability, sexuality, environment, youth, sub-cultures, fundamentalisms, and more. The so-called ‘cultural turn’ is thoroughly evident in critical geography for intellectual shifts attendant upon the transition from modernity to postmodernity have heightened the significance of culture, identity and consumption and lessened the significance of economics, social class and production. Why the ICGG is critical . . We are CRITICAL because we demand and fight for social change aimed at dismantling prevalent systems of capitalist exploitation; oppression on the basis of gender, race and sexual preference; imperialism, neo-liberalism, national aggression and environmental destruction. We are CRITICAL because we refuse the self-imposed isolation of much academic research, believing that social science belongs to the people and not the increasingly corporate universities. We are CRITICAL because we seek to build a society that exalts differences, and yet does not limit social and economic prospects on the basis of them. We are CRITICAL because in opposing existing systems that defy human rights, we join with existing social movements outside the academy that are aimed at social change. http://econgeog.misc.hit-u.ac.jp/icgg/ The social construction of space, place and nature The case for border geography • • • • • Only a minority of critical geographers seek to marry research and teaching with social and political activism – geography fails to ‘make a difference’ Changes in how academic labour is valued since the early 1980s have allowed CG to flourish because it can be abstracted into the ‘contentless currency’ of RAE/QAA culture The forces that allow CG to blossom are also those that label such activities as working with school teachers as non-academic and invaluable Time for CGs to debate the moral and political economy of the academy; rethink the role of transformative intellectual; and devote more effort to a border geography that can transcend the divide between academic and non-academic communities Action research offers a way of doing geography that connects with the marginalized – of geographers occupying a ‘third space’ of critical engagement between the academy and the activist (see K&H, 1999 for case studies) Kitchen & Hubbard, 1999, Castree, 2002 From radical to critical education Critical pedagogy 1: education as praxis All knowledge starts from activity in the material world and returns to it dialectically. Theory is a guide to practice and practice a test of theory. Critical pedagogy claims that knowledge and truth should not be products to be transmitted to students, but practical questions to be addressed as students and teachers create and re-create knowledge by reflecting and acting on significant events and issues that affect their everyday lives. Four principles of dialectics: - Totality - Movement - Qualitative change - Contradiction Critical pedagogy 2: students as researchers • • • • • • Pupils are active in the learning process and much learning is experiential Pupils are taught to think critically as they investigate issues relevant to their present and future lives Pupils develop a critical understanding of their own histories and futures Pupils learn about existing social and cultural structures and processes and more democratic alternatives Pupils clarify and develop values Pupils develop the knowledge, skills and values required by active and critical citizens Critical pedagogy 3: teachers as facilitators • Teachers are co-researchers with pupils into the structures and processes that prevent/encourage social justice and sustainability • Teachers share their aims and theory with their pupils • Teachers organise democratic, informal yet intellectually disciplined classrooms • Teachers encourage students to see themselves not as consumers but as producers of knowledge • Teachers relinquish their authority as truth providers and assume the authority of facilitators. State restructuring of education NC, SATS, league tables, Ofsted, TTA. Intensification of treachers’ work. Criticism of ‘trendy’ teachers and teacher educators. Part time contracts. Performance related pay. Classroom assistants. General Teaching Council. Increased managerialism.Requirements of QTS. Attacks on comprehensive principle. Specialist schools. Marginalisation of theory in teacher education and CPD. Erosion of space for critical reflection and autonomy of teachers and teacher educators. PFI and corporate funding of schools. Differentiation and increased marketisation of schooling. Classroom assistants. See Hill, 2001 Re-imagining space Space and society – the dialectic • • • • • Empty space as a container of human activity Space is unproblematic – where things happen An a-political space, serving as ideology by neutralising existing spatial arrangements Still accepted in school geography but not in the parent discipline Space as HOMOGENEOUS, CONTINUOUS, OBJECTIVE, CARTESIAN AND KNOWABLE • • • • Produced space, a medium through which social relations are produced and reproduced Neglected in social theory compared to time – “geography matters” – history is made on, rather than in or through, space In PM society, multiple spaces and identities form the basis for new forms of politics Space as FRAGMENTED, IMAGINATIVE, SUBJECTIVE AND UNKNOWABLE Morgan, 2000 A critical pedagogy of space 1 Pupils should learn how space is: • enabling and constraining: • filled with power and ideology at all scales • structured, contested and argued over with multiple points of resistance – although class may still be ‘key’ • medium for identity formation and experimentation with alternative lifestyles and communities • made and can be remade in more sustainable forms Morgan, 2000 A critical pedagogy of space 2 Globalisation: • leads to feelings of dislocation and disorientation – increased reflexivity an opportunity for CP • challenges modern education’s spaces of enclosure – eg. the subject, the classroom • prompts education for global citizenship and PM forms of CP than can encourage discursive democracy via new modes of knowledge production (but note contradictions of cyberspace) • Requires pedagogies of (dis)location to make learners reflexively aware of forms of counter and disidentification and to develop awareness of shifting coalitions of resistance eg. anti-globalisation movement Edwards & Usher, 2000 Children and Identity • All of us come to be who we are (however ephemeral, multiple and changing) by being located or locating ouselves (usually unconsciously) in social narratives largely of our own making. • These narratives are spatially and temporally specific • Children are homogenised (by compartmentalisation, spatial segregation and familialisation) and at the same time individualised (by rights, commodification, consumption) • Children are ‘strung out’ between competing definitions of their ‘identity’ – between different structures of meaning – particularly within their peer culture with its power to include or exclude • School plays an important role in shaping children’s identities via for example the formal and informal worlds of the lunchbreak Space and identity in schools Here space is crucially important. A fractured geography of sites from the home and adult-regulated world of the dining hall to the diverse microgeographies of the lunch break underlie the processes through which children’s identities are taken up and contested. Notably the lack of adult regulation within the children’s lunch break world enables hegemonic groups of girls and boys to take up and occupy particular spaces in ways which reproduce their dominance and submerge other identities. The importance of these spaces in creating and sustaining a social order within the school suggests that there is a need for geographers interested in children and childhoods to pay more attention to exploring these neglected geographies. Gill Valentine, 2000, p. 266 QCA Unit 1 (Yr 7) Making connections The main purpose of this unit is to further develop pupils’ knowledge and understanding of places. Pupils investigate some of the features and characteristics of the area around their new school while also developing a range of geographical skills. Key aspects include: Pupils asking geographical questions Pupils describing and explaining human features Pupils exploring interdependence and global citizenship Where is our place and what is it like? map skills, concept of ‘our place’, characteristic features, field sketch, top 10 features from survey, persuasive writing about ‘our place’ Changing social practices and . narratives in the school dining hall. Food practices as a form of control Social and spatial divisions in the playground. Significance of the body – territories based on size and age – boundaries – toilet as an imagined space of becoming adult for Yr9 girls – Yr 9 boys and the off licence, the football field – different kinds of masculinity and femininity – loners. How is our place connected to other places? brainstorm connections and links, maps and diagrams, shopping survey, origins of building styles/materials/uses concepts of location, context, connection, pattern Links between food practices and culture in the school and those in the wider world. Constructing identity through diet – the role of advertising and peer pressure – eg what British Asians eat at home and school Influence of global youth and consumer culture on playground differentiation – fashion, music, computer games, brands – making the global local. What do we know, think and feel about other places? review KS2 contrasting localities, locate them, similarities and differences, places we would like to visit, different perceptions of these places How do children form identities in other parts of the world – what options do different spaces/places provide? How do children elsewhere cope with the tension between homogenisation and individualisation? Are spaces of childhood sexualisation, such as Girl Heaven, desirable? Re-imagining nature The social construction of nature • Modernity and society-nature dualism (human vs physical geography) S/N seen as fundamental, unquestionable. • But N is S and S is N. Nothing unnatural about humans or indeed cities. Counters ideologies of nature. • Focus shifts from N>S or S>N to who constructs what kinds of nature(s) to what ends and with what social and ecological effects. (Construction is both material and discursive) • Critical social theory reveals how natures are made and can be remade – allows new forms of nature/environmental politics • Two versions of SC argument: 1 nature can only be known through culture, 2 nature is increasingly engineered and produced for profit. • But nature not wholly social, biophysical processes at work Braun & Castree, 2001 Themes from political ecology • • • • • Political economy Environmental justice Gender and the household Environment and livelihood movements Environmental history (including ecological imperialism) • Ideology and scientific discourse • The body, identity and consumerism Unit 14 Can the earth cope? Ecosystems, population and resources This unit is in two parts: ecosystems, population and resources; and global futures/resource issues. Pupils investigate the global distribution of one or more selected biome, populations and the resources of food production. They find out about the relationships between these three themes and about resulting environmental issues/consequences. Key aspects include: Knowledge and understanding of patterns and processes through an exploration of ecosystems and resource issues Knowledge and understanding of environmental change and sustainable development How are population and resources interrelated? Arrive at an ‘appropriate’ definition of natural resources by discussion. Use thematic maps of the world to investigate pupils’ enquiry questions eg possible factors influencing population density (environmental determinism) Make a diagram summarising the interrelationships discovered Use an atlas for clues to match location cards to resource cards The social determination of resources. The role of land, labour and capital in different modes of production. Resources and the global economy – global flows of energy and materials ecological footprints. Population density and migration as a response to past and present levels of development and underdevelopment What are the effects on the environment of this resource issue? Choose a topical resource issue. Provide text based resources expressing arguments for and against Pupils highlight facts and opinions in different colours; identify interested parties, create a matrix. Plot resource issue locations on a world map. Debrief Is the war in Iraq a war about oil? See examples in next three slides Pupils engage in ideology critique. They seek to understand the power and interests shaping the views expressed in each text based resource. Bomb before you buy Naomi Klein, The Guardian, 14.4.03 So what is a recessionary, growth-addicted superpower to do? How about upgrading from Free Trade Lite which wrestles market access through backroom bullying at the WTO, to Free Trade Supercharged, which seizes new markets on the battlefields of preemptive wars? After all negotiations with sovereign countries can be hard. For easier to tear into the country, occupy it, then rebuild it the way you want. Bush hasn’t abandoned free trade, as some have claimed, he just has a new doctrine “Bomb before you buy”. . . . Investors are openly predicting that once privatisation takes root in Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait will be forced to compete by privatising their oil Its all about control, not the price of petrol Mark Almond, New Statesman, 7.4.03 • US strategists seek a monopoly of the global oil market as a means of disciplining potential future rivals • Doctrine of pre-emption carried out in Iraq implements a strategy designed to prevent challenges to US hegemony in the post cold war era. • Real targets are outside the Arab world – China and India – they could challenge US hegemony but are also dependent on oil imports as their economies and populations grow • US plans for post-war Iraq include privatisation of the oil industry • If Iran were to follow Iraq (and Central Asia) under a US sponsored regime, China could find its oil supplies controlled by Anglo-American companies. US could turn off Chinese economic boom. Causa Belli by Andrew Motion They read good books, and quote, but never learn a language other than the scream of rocket burn Our straighter talk is drowned but ironclad: elections, money, empire, oil and Dad In a World Gone Mad by the Beastie Boys First the “war on terror”, now war on Iraq We’re reaching a point where we can’t turn back Let’s lose the guns and let’s lose the bombs And stop the corporate contributions that they’re built upon Well, I’ll be sleeping on your speeches ‘til I start to snore Cause I won’t carry guns for an oil war Why should we study resource issues? Locate all resource issues studied on a world map Which issues have/will affect our lives? Introduce probable and preferable futures. Pupils draw a cartoon of their preferable future and write their own definition of sustainable development. • values and attitudes • global interdependence • citizenship Locate all past and potential future wars which may be about resources on a world map? Are resource wars likely to be more frequent in the future? Sustainable alternatives to oil based economies. In what ways can global governance (multilateralism) promote sustainable development and so lessen the likelihood of resource wars? Opportunities for critical school geography • The key stage 3 strategy in foundation subjects that seeks to improve motivation, engagement and thinking skills • The creativity initiative that seeks to engage, motivate and interest pupils - ‘be surprising, controversial, topical, and provocative’ • The geography and history curriculum project that seeks to make the subjects responsive to a changing world – critical approaches to knowledge; processes that shape economy, society and environment, critical engagement with issues, global citizenship, futures perspectives; relevance • The pilot GCSE to reflect changes in the subject • The geography matters strand on the QCA website. http://john.huckle.org.uk