yom kippur 5776 learning from our students

advertisement

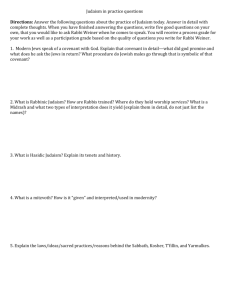

YOM KIPPUR 5776 LEARNING FROM OUR STUDENTS “Who is wise? The one who learns from all people.” These High Holidays we have learned from a plumber on Erev Rosh Hashana, from the synagogue’s custodians Joe, Dennis, and Gilbert on Rosh Hashana Day, from Jack Coulter and the greatest generation on Rosh Hashana, and last night on Kol Nidre we got into an imaginary time machine and learned from the clergy that served this congregation in the 1960s, Rabbi Harold Schulweis and Cantor Simon Cohen. It is only fitting that the last sermon of the High Holidays looks not back to the past, but forward to the future. Today we will have the opportunity to learn from some of our students in consonance with a different quotation from the Talmud. In tractate Taanit 7a, Rabbi Chanina says: “I have learned much wisdom from my teachers and even more from my colleagues. However, from my students I have learned most of all.” So today we will focus on some teaching by our own Temple Beth Abraham students, specifically our Confirmation students from last year. Before we do that, though, it is important to set the context. It is especially appropriate to quote the tractate Taanit during the Yom Kippur fast, since Taanit means fasts, and this entire tractate is devoted to the laws surrounding fasting. The specific context of the quotation is a discussion about fasting for rain, the subject of my sermon last year, and the rabbinic sages say that the day of fasting for rain is as important as the day of matan Torah, the day of the giving of Torah. While on that subject, they compare the Torah to a tree, an etz chaim, a tree of life. And Rabbi Nachman bar Isaac says that the reason the words of Torah are likened to a tree is to teach us that “just as a small tree may set on fire a bigger tree, so too it is with scholars, the younger sharpen the minds of the older.” And then he quotes Rabbi Chanina about learning most of all from his students. The metaphor of the trees on fire is especially resonant with me. Teaching children provides the very fuel that makes my rabbinate burn. One of the main reasons I became a rabbi was the opportunity to work with children of all ages: preschool, Bet Sefer, Bar/Bat Mitzvah, and Confirmation. There is a Midrash I often tell at baby namings, how when God sought someone from the Jewish people to guarantee the covenant at Mount Sinai, Moses, Aaron, and the elders offered up themselves as surety but God told them that none of them were good enough. Who, then, could guarantee the covenant, which is essentially a contract 2 between God and the Jewish people if not Moses, Aaron, or the elders? The answer: Only the children were good enough to make that guarantee. And we know this to be true. It’s why educating our children is such a point of emphasis here at Temple Beth Abraham, from preschool through Confirmation, and having the students continue through Confirmation is both the goal and the expectation here. I have essentially three goals for our students. By the time they leave our community, I hope they leave here with three things. The first is synagogue skills. It’s why we emphasize learning prayers, davening, learning to decode Hebrew reading. I want our children to be able to go to any synagogue in the world of any denomination and feel comfortable. Secondly, I hope they leave with a positive Jewish identity. This is a little more difficult to measure and define, since it means different things to different people. Some identify with the social action aspect, others with the life cycle, others with the peoplehood, others with a connection to the land of Israel. Whatever the “hook” may be, we hope our students develop this positive sense of Jewish identity. Finally, we hope they leave here with friends. It’s why we have Share-a-Shabbat dinners when they are young, why we insist that every Bar/Bat Mitzvah student invite their entire class not only to their service but to their party, and why we offer such strong support to our youth groups Oakland BBG and Dreidel AZA. They are not as synagogue centered or religious as I would like them to be, but dayenu. It’s Jewish kids getting together and building lifelong friendships. All of the teachers here hope that at least a few sparks have been lit in your children by our teachings here at Temple Beth Abraham. Once in a while, you get to see flashes of those sparks, and one such moment is during the late Spring every year on a Friday night near the holiday of Shavuot where we hold our Confirmation services. Every year I am moved by these drashot or “speeches,” but this year I was especially moved, because the five students who volunteered to speak, all of them female, interestingly enough (that’s a subject for another time, perhaps) really captured the essence of what it is we are trying to teach them about Judaism—the struggle, the theology, the action, it was all in there. What is Confirmation? You may have seen the photos on the walls. Essentially, it’s a class for 10th graders that meets on Wednesday evenings from January through May, and even students we haven’t seen since Bar/Bat Mitzvah days usually come back for the class. The class itself is called the “Bible Meets Modernity,” and each week we take a different book of the Bible as well as a contemporary issue which is addressed or hinted at in that book. For instance, week one is Genesis and God, week two Exodus and Abortion, and there 3 is a lesson for every book in the entire Tanach. The assignment in the drash was to give a two-four minute speech about what in Judaism is meaningful or significant to them, utilizing something they learned in the class. I want to share excerpts from the five incredible students who chose to speak. Sonia Aronson talked openly about her struggles of what it means to be Jewish. Being Jewish has always been very confusing for me because I felt I never knew what being Jewish truly meant. There were, and are, so many aspects that contradict each other. When I started elementary and later middle school, where I was one of the only Jewish kids. I looked up to my school friends and wanted to be like them, and resented being Jewish because it made me different. However, as I got older I began to appreciate my Judaism more because it set me apart from my friends, and, in general, allowed me to do different things and meet more people. In Confirmation, we discussed similarities that as Jewish teens we all share. But most of us all differed in some way—whether it was how we connect with God, how our families view interfaith marriage, or even which Jewish activities we participate in –which led me to realize that everyone has a different relationship to Judaism and that our connections to the religion will constantly change and develop. Sonia has named the struggle that so many of us have with Judaism, and this idea of struggle is so Jewish in itself. After all, our name Yisrael literally means to struggle with God. Judaism really does contradict itself in many ways. Many of us struggle with our beliefs, our level of observance, how assimilated we want to be or how much we want to turn inward in our Jewishness. Thank you Sonia, for your honesty and openness in addressing what so many of us face. Despite the fact that Judaism can be a struggle and can contradict itself, Sophie Govert reminded us that Judaism is not a “whatever you want it to be” religion either. Here are her words: One of the most important things I learned in confirmation wasn’t exactly in a lesson plan. It was said in passing, by Rabbi Bloom. It was something like, “Judaism isn’t whatever you want it to be.” And then something else about “but hey, don’t’ worry, because there is a lot up for interpretation.” Sophie then talked about how she had been treating Judaism as whatever she wanted it to be for most of her life, making it convenient for herself instead of asking the tough questions. And many of us do the same. We simply state our beliefs, whatever they are, and say “that’s the Jewish view.” Writers and Jewish 4 leaders do this all the time as well. Read Tablet or Ha’aretz or The Forward or the J. The writer will set out his or her political beliefs and then define them as “the Jewish view.” But Judaism isn’t all things to all people. It’s a religion based on mitzvoth, specific commandments, and middot, specific values. They are subject to a wide swath of interpretation, but they don’t simply go with whatever the prevailing social winds are. So Sophie said: But we did ask tough questions over the course of the class. How strongly do we believe in God, if we even believe in God at all? How important do we feel it is for each of us to raise Jewish children? How do we reconcile who Leviticus says we can’t be with who we are? So even if Judaism is not exactly what I want it to be, at least I’ll always be allowed—and encouraged—to ask why that is. Thank you Sophie. You captured exactly what I believe too, but you put it much better than I ever could. Speaking of tough questions, two of our students, Ruby Klein and Aviva Davis, grappled with one of the most difficult questions of all—God. But they addressed it head on, and they didn’t fall back upon a generic, God as some sort of higher power but I can’t say what/ Ruby went straight for one of the greatest Jewish theologians of all time, Maimonides. Here is what she said: Maimonides’ idea posited God as a unity that sent power through angels of pure intellect, which makes our role to strive to achieve intellectual perfection and share that knowledge with each other. We become God’s angels, which makes Judaism a vehicle to understand, to ask questions, and learn as much as we can through each other. In other words, by striving for knowledge and sharing that knowledge with one another, God’s holiness is present in our world. The discussion of Maimonides, Ruby said, transported her back to one of the times she felt closest to Judaism, which was during the congregational trip to Israel. Throughout the entirety of my time in Israel, I kept asking myself “Where is the holy in Israel? At which location am I closest to G-d? Is it the holy in the western wall or the synagogues or the beach?” I didn’t have my answer until one of the last days in Israel, when I concluded that the holy is within the people, and just as our words are G-d’s transcended power to Earth, the people that travel the streets of Israel carry its holiness. What beautiful, intellectually profound thoughts from Maimonides via Ruby. As Maimonides himself said in the Mishneh Torah, “let the honor of your students should be as dear to you as your own." Indeed it is Ruby. Aviva also dealt with one of the challenges many of us face regarding God. Referencing the Akeidah, the binding of Isaac which we read last week on the 2nd 5 day of Rosh Hashana and presents a very troubling view of God, to say the least, she asked: What do we do with God in the Torah who has the power to instill fear, anxiety and panic among us? She interviewed a number of her peers, and 3 out of 4 did not believe that God was present in their lives. She then added, perhaps a little tongue in cheek Why would they need to when they have parents to provide healthy, organic food, homes in the hills, and higher education? A decrease in blind faith might be a good thing, but for those of us whose needs are met, are there other ways to honor the mystery in our lives? I choose to honor God through observing Shabbat and communicating with other Jews. That kind of thinking honors both God and community, Aviva. Finally, Sarah Weintraub moved us from philosophy to action. It is not what one says but rather what one does, that makes all the difference in the world.” She then went on to talk about Tikkun Olam, not in the generic sense that it is often used today, but explaining the actual Kabbalistic, Jewish mystical view which presents an alternative view of the creation story. When God created the world on the first day of creation, there were these vessels of light that became so intense, they shattered into billions of pieces. It was a cosmic catastrophe. Our task, in partnership with God, is to pick up the sacred fragments by doing mitzvoth, whether we are talking about feeding the hungry or lighting Shabbat candles. The underlying meaning of this value is that the world we are living in today is imperfect and each of us, meaning you and me, are obligated to do something about this imperfectness. Sarah, thank you for picking up a fragment through your words. Five important lessons from five very special students, lessons that including naming our struggles, that Judaism is not whatever you want to be, but that there is much room for interpretation, that God is present when we share our deepest thoughts with one another, that concrete actions of Tikkun Olam are what each of us must do to make this world a better place. This is exactly what I want our students to take away from Temple Beth Abraham about Judaism, but it’s like a mirror. Here are the students reflecting our teaching back at us, but seen in a newer light, with their own relevance. In a few hours we will conclude Yom Kippur with our Neilah service. It opens with a piyut called “El Nora Alila,” written in the 11th Century by Abraham 6 ibn Ezra, sung here in a tune which I can’t hear without thinking of Sarah Sheidlower of blessed memory. The final stanza of this poem begins with the words Tizku l’shanim rabot habanim v’habanot, may we, your sons and daughters your children, be merited with length of days and with ditzah uvtzohola, joy and gladness. The joy of children begins our neilah service. Then, as we get to the end of Neilah, Avinu Malkeinu, one of the last lines is “chamol aleinu v’al olaleinu v’tapeinu, Merciful One, who gives us life, have compassion for us, our infants, and our children.” Before the gates close, we refer not to ourselves, but to our children, who are ultimately both the repository and the source of ultimate wisdom. And then, the very final line, after reciting the Shema and that Hashem is God seven times, the very final line is “l’shana haba’ah b’Yerushalayim, next year in Jerusalem.” Yes, it is a reference to the our sacred land at the crescendo of the service, an important lesson in and of itself, but I think it’s also symbolic—the idea that we must look not just to God but to the future itself, to next year, and to the only ones who can guarantee the covenant and future of the Jewish people—our children. And, thankfully, as you can see, our future is in excellent hands.