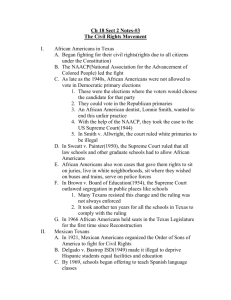

U.S. Supreme Court, Brown v. Board of Education

advertisement

U.S. Supreme Court, Brown v.

Board of Education (1954)

Charles Houston

Thurgood Marshall

Earl Warren

Background

Charles Houston

• Attended Amherst College and Harvard Law

School.

• He became the first African‐American member

of the Harvard Law Review in 1921.

• Joined the law faculty at Howard University in

1924, where he was academic dean from 1929

to 1935.

• Was head of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund

from 1933 until his death in 1950.

Background: Thurgood Marshall

• Born July 2, 1908 in Baltimore, MD.

• Received his B.A. degree from Lincoln University

in 1930.

• Studied under Charles Houston and graduated

first in his class from Howard Law School in

1933.

• He was enlisted to help with the civil rights battles being

waged by the NAACP after graduation.

• Took over the Legal Defense Fund, after Houston’s death in

1950.

• Argued the Brown v. BOE case for the first time in 1952.

• A divided court asked to have the case reargued in October

1953.

• On May 17, 1954, the court unanimously ruled in favor of

Brown.

Chief Justice Fred Vinson

President Dwight Eisenhower

Chief Justice Earl Warren

Background: Chief Justice Earl Warren

• Republican attorney, who served as governor of California from 1943-1953.

• Warren lost the presidential nomination in 1952 to Eisenhower.

• President Eisenhower nominated Warren for the Supreme Court and was sworn in

as Chief Justice on October 5, 1953.

• Eisenhower later regretted his choice. He had hoped to appoint a moderate

conservative, but Warren proved to be an unabashed liberal.

Historical Background

• Linda Brown was a young black girl that was a student in a

segregated school. She had to cross railroad tracks and ride

a school bus twenty-one blocks to a black school, even

though there was a white school only five blocks away. The

attorneys forced the court to answer why African

Americans were singled out for different treatment. The

attorneys also made the point that racial segregation

deprives students of important interaction with others that

enhances learning on May 17, 1954. The courts ruled in

favor of desegregation on the grounds that separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal since they

deprive minority student’s equal educational opportunities

essential to their success in life.

THE ISSUE OF SEGREGATION OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOCUSED ON THE

AFRICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY.

THE INTEGRATION OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS MET STRONG WHITE OPPOSITION.

“Americans had always believed that the public schools were agents for social

advancement, and the possibility of integration conjured up white persons’

fears of interracial marriages, moral decay, and collapsing academic standards.

Besides, for most white Texans, segregated public institutions validated the

presumed inferiority of black persons.” (p. 370)

Calvert, De León, Cantrell, p. 370.

SWEATT v. PAINTER: Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP argued that lawsuits

forcing black enrollment in professional and graduate schools would least

antagonize whites. The NAACP decided to sue the University of Texas for the

admission of a black student to its school of law on the grounds that no school

in Texas offered black people a law education. Heman Marion Sweatt, a

Houston post office employee, agreed to become the plaintiff and seek

admittance to U.T.’s law school. The conservative leadership in the state

attempted to thwart the suit by broadening educational programs at Prairie

View State Norman and Industrial College and changing the name of that

institution to Prairie View University, incorporating Texas Southern University

into the state system, and establishing an all-black law school in the basement

of the state capitol.

Calvert, De León, Cantrell, pp. 370-371.

In response, NAACP attorneys

changed their strategy to one

that argued that the University

of Texas’s excellent reputation

in law meant that any rival

segregated institution

necessarily offered an inferior

degree. The Supreme Court

agreed in the 1950 Sweatt v.

Painter decision and ordered

the integration of U.T.’s law

school.

Thurgood Marshall with

James Nabrit Jr. and George

E.C. Hayes after their victory

in the Brown v. Board of

Education case before the

Supreme Court, May 17,

1954.

The Fiftieth Legislature established

Texas Southern University and

expanded graduate education at Prairie

View A&M in an attempt to thwart

Heman Sweatt's application to enter

the University of Texas.

In Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (1954), the

Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were

inherently unequal and thus unconstitutional.

A public opinion poll reported in 1955 that white Texans

opposed integration by four to one, whereas black

Texans supported desegregation by two to one.

Court Decision: “We conclude that, in the field of public

education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no

place. Separate educational facilities are inherently

unequal.”

Calvert, De León, Cantrell, p. 372.

Linda Brown and her new class mates after the Supreme

Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

NAACP lawyers congratulate each

other on the decision in Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka

(1954). Attorney Thurgood

Marshall, center, was later named

the first African American justice

of the Supreme Court.

Case Background

• The case of Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, Kansas combined four cases challenging

racial segregation in public schools. In addition to

Topeka, districts in Delaware, South Carolina, and

Virginia participated in the lawsuit.

• In Brown v. Board, 13 parents of 20 students filed

suit in the U.S District Court of Kansas to

challenge the 1896 ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson,

which made racial segregation legal through its

"separate but equal" clause.

Case Background Cont.

• A Kansas statute allowed cities with populations of

over 15,000 to provide separate schools for AfricanAmerican and white students. These 13 parents were

urged by the NAACP to enroll their children in

neighborhood schools, rather than allow them to be

bussed to one of the four African-American schools.

Each of the students was denied enrollment.

• When heard in the U.S District Court, the court

concurred that segregation was harmful to the AfricanAmerican students. However, the ruling itself favored

the school board, and enrollment for these students

was denied.

Main Points

• Separate is inherently unequal.

“The plaintiffs contend that segregated public

schools are not “equal” and cannot be made

“equal,” and that hence they are deprived of the

equal protection of the laws…”

“We conclude that in the field of public education

the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently

unequal.”

Main Points Cont.

• Education is a right, not a privilege.

"In these days, it is doubtful that any child

may reasonably be expected to succeed in life

if he (or she) is denied the opportunity of an

education. Such an opportunity, where the

state has undertaken to provide it, is a right

which must be made available to all on equal

terms."

Main Points Cont.

• Segregation is a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

because it denied people equal protection of the law.

“In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back

to 1868 when the Amendment was adopted, or even to

1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson was written.”

“Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly

situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by

reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment.”

“This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion

whether such segregation also violates the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment…”

After the Courts Ruling

• Massive resistance followed the decision. Rather than desegregate

as ordered by the U. S. Supreme Court, some state governments

defied the Court

• National Guard troops were called out to escort African American

students into formerly all white schools.

• Freedom of Choice schemes were used to circumvent

desegregation. New York Times reporter Adam Cohen in his

January 18 article "The Supreme Struggle" said "Southern states

adopted legal tactics to stall integration, notably "freedom of

choice" plans. In theory, freedom of choice allowed blacks to

attend any school in a district, but black parents were threatened

with losing their jobs and homes – and having crosses burned on

their property – if they tried to send their children to white

schools."

Governor Allan Shivers Opposed Desegregation: “Governor Shivers was a staunch advocate of

states rights, and believed that Texas should resist any federal attempts to integrate the public

schools. Many white Texans agreed with him, and his mailbag was flooded with letters, many of

them unprintable, opposing integration. In 1956, the Mansfield school district near Fort Worth

was the first in Texas to be ordered to desegregate. An angry mob prevented three black

students from entering the high school. Shivers ordered the Texas Rangers to the town to

protect the mob and prevent the students from attending school. The Eisenhower

administration, in the middle of a reelection campaign, did not intervene. Shivers' example

inspired Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus the next year in his resistance to the desegregation of

Central High in Little Rock. In that case, the federal government sent in the Army and enforced

the law of the land. In the years that followed, many Texas school districts willingly

desegregated, but others held out until 1965, when the federal government threatened to

withdraw funds.”

DOCUMENT: Levelland constituent V. McMurry

urges the governor to continue his fight to

maintain segregated schools and to keep the

tidelands in state control.

SOURCE: V. McMurry to Shivers, January 10, 1955,

Records of Allan Shivers, Texas Office of the Governor,

Archives and Information Services Division, Texas

State Library and Archives Commission.

http://www.tsl.state.tx.us/governors/modern/shiversmcmurry.html

Desegregating University of North Texas

In December 1955, U.S. District Judge Joe Sheehy issued an injunction prohibiting North Texas from denying admission on

the basis of race. Atkins already had enrolled at Texas Western in El Paso, but the door he opened led to the arrival of North

Texas' first African American undergraduates and master's students in 1956.

Irma E.L. Sephas began classes with little notice in February 1956, the same day a screaming, rock-throwing mob threatened

Autherine Lucy as she entered the University of Alabama. After three days of violent rioting, the university expelled Lucy,

saying it was for her own safety.

Determined to prevent similar scenes in Denton, Matthews ordered a virtual news blackout and kept television cameras out

of classrooms. He even refused to brag about North Texas' peaceful desegregation.

"President Matthews' primary concern was that to point to the fact that nobody was

throwing rocks at Sephas was to invite somebody to come and throw rocks at her,"

said James Rogers in a 1980 oral history interview. Rogers, now a Professor Emeritus

of journalism, was university news director when Sephas arrived.

Yet, there were ugly incidents, Matthews said. Racial epithets were chalked on

sidewalks, but crews were out before classes began to scrub them off. Crosses were

burned in front of the administration building and at Matthews' home, but they

were extinguished without publicity.

The freshman class: That summer saw several more African American students at

North Texas, and in Fall 1956, the first group of freshmen enrolled. Among them

were two young athletes, Leon King ('62. '72 M.S.) and Abner Haynes ('62), who

integrated the North Texas freshman football team 10 years before an African

American played in the Southwest Conference.

Source: The North Texan Online

http://www.unt.edu/northtexan/archives/s04/history.htm

Above: North Texas students Bettye

Morgan ('60), second from left, and

from right, Burlyce Sherrill Logan,

Floydell Barton Hall ('60) and

Barbara Beverly Kincaide ('57) pose

with friends on campus in 1956.