Theories of Morality - Fort Thomas Independent Schools

advertisement

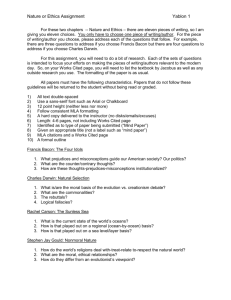

Theories of Morality Kant Bentham Aristotle Morality Morality: Action for the sake of principle Guides our beliefs about right and wrong Sets limits on desires and actions Where does Morality get its Authority? (1) God (2) Parents (i.e., commands, threats, modeling) (3) Society (i.e., laws, mores, folkways) Common Considerations in Morality Should we follow rules/laws when it conflicts with our conscience? Ought we follow our conscience? Why/Why Not? Should we emphasize rules/principles or character/virtue? What makes a law/principle moral? 3 Key Groups of Moral Theory: 1). Duty-Defined Moralities (Immanuel Kant) Based on Authority The principle itself that ought to be obeyed 2). Consequentialist Moralities (J. Bentham) Based on the results of actions Principle/Authority holds no moral weight 3). Virtue Ethics (Aristotle) Based in Authority & results of actions Virtues benefit the overall community & individual One should avoid excess and deficiency Immanuel Kant’s Categorical Imperative Categorical: Without Qualification Imperative: Command/Order Kant believed that our actions were not as important as our intentions in morality Kant also believed all humans were capable, through reason, of figuring out right/wrong. Reason is an authority ‘in’ us but it transcends us Why be Moral?: “It is the rationale thing to do.” Kant’s Categorical Imperative 1). Act only on that maxim [intention] whereby you can at the same time will that is/should be a universal law. 2). Act as if the maxim of your action were to become by your will a universal law of nature 3). Always act so as to treat humanity, whether in yourself or others, as an end in itself, never merely as a means 4). Always act as if to bring about, and as a member of, a Kingdom of Ends (that is, an ideal community) The Utility Principle: “Always act for the greatest good for the greatest number of people.” Places all emphasis on the actual consequences and insists morality is only justified by positive effects (how happy they make us) For Bentham (pictured above) one shouldn’t ask the Kantian question: “What if everyone lied?” but instead: “What would be the actual consequences of me lying?” Duty-defined makes no appeal to happiness/actual consequences (usually intended consequences) Key Difference between Bentham & Mill: Quantity vs. Quality For Bentham factors include: length, intensity, certainty of result, speed of result, number of people affected, mixture of pleasure/pain For Mill: He insisted that there are different qualities of pleasure and pain as well as different quantities. It is better to be satisfied with a lower amount of a higher pleasure. I.E.: “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.” pg.265 Aristotle: Virtue Ethics & The Doctrine of the Mean Virtue: Morally good habits needs teaching & repetition Why be moral? So our lives go well (achieve Eudemonia) Usually we think of this as a selfish want, but Aristotle points out that people only think of their life as going well when the one’s they care about are also doing well. Are you happy when ________ is upset? Morals must be habituated (made habit) through practice What does this say about “Protecting our children from tough material?” The Virtues of Living Aristotle tries to create a list of universal virtues that any human needs to ensure their life goes well (achieves Eudemonia). He attempts to use only those which are fundamental, universal facts about human nature. Courage, Temperance, Generosity, Self-control, Honesty, Sociability, Modesty, Fairness (Justice) Character plays a large role in Aristotle’s model as well. It ties into habit. Our character is what we repeatedly do (e.g. I am a thief because I often steal). Character is built up in our actions whenever we choose between what we would like to do and what we should do The Doctrine of the Mean Each of the virtues lies at a mean between two extremes (excess or deficiency). Courage, therefore, lies at the mean before the excess (rashness) and deficiency (cowardice). This is not a mathematical system. If eating 100 apples is too many and eating 0 apples is too few, that does NOT mean that eating 50 apples is the mean. Instead, mean is determined rationally (“as a prudent man would determine it”) Thus, the proper mean is relative to the individual, not the situation. “In this way, then, every knowledgeable person avoids excess and deficiency, but looks for the mean and chooses it”