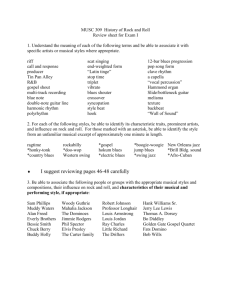

Women and Music: A historiography

advertisement

Introduction 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM Scope of Course 1. Women and Music: Three Approaches Women’s Music-Making in Society: A global view Herstory: Women in Western Art Music to 1900 Women in 20th Century and Contemporary Music 2. Music Written by Women We will be studying music composed by women, whether songs by Joan Baes or symphonies by Louise Farrenc. We will be examining the parameters, constraints and opportunities for women creators, and study the interplay between social context and musical creation. 3. Music Performed by Women Not all of women’s music was written by women. Some were written by men for men, but appropriated by women; some were written specifically for women performers; this is valid in both art music and popular music, and we will be studying what it means if a woman appropriates a male-gendered voice, and – on the other side – how women perform music gendered female composed by men. Two music examples: The Argentinian singer, Mercedes Sosa and Violeta Parra’s song: “Gracias a la vida” Jazz diva, Ella Fitzgerald, performs Cole Porter’s “You’d be so nice to come home to” Uncovering Women’s Music 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM A historical and critical perspective Women and Music: A historiography Early Key Texts in the Historiography of Women Musicians September, 1847 o Maurice Bourges: “Des femmes-compositeurs,” Revue et Gazette musical de Paris First article series dedicated to women composers as a distinct group of musical creators 1876 o Fanny Ritter: Woman as a Musician: an Art-historical Study A study sponsored by the Association for the Advancement of Women 1888 o A.T. Michaelis, Frauen als schaffende Tonkunstler: ein biographisches Lexikon A 55-page dictionary of women composers, probably the first dictionary dedicated to women composers 1895 o Eugene de Soleniere: La Femme compositeur A 57-page book written by the French librettist, poet and music critic. It contains an introductory text, biographic sketches of contemporary women composers and a short dictionary of women composers. The author planned to write a more substantial history of women composers, but died at age 31 in 1904, during his research on the book. He described his new project on women composers as “a critical and documentary study, followed by a biographical and bibliographical dictionary of women’s composition from Antiquity to today.” 1902 o Otto Ebel, Women Composers: A Biographical Handbook of Women’s Work in Music First major dictionary dedicated to women musicians, with more than 750 entries. It is translated into French in 1908 as Les Femmes compositeurs de musique. 1903 o Arthur Elson: Women’s Work in Music A history of women’s roles in music, from antiquity to the beginning of the twentieth century. Women as muses, performers and composers. 1917 o Kathi Meyer, Der chorische Gesang der Frauen: Teil 1: Bis zur Zeit um 1800 One of the key early 20th-century study of female musical groups 1948 o Sophie Drinker. Music and Women: The Story of Women in Their Relation to Music First large-scale feminist study devoted to women in music Topical and multicultural approach, using anthropological, iconographical, mythological, and historical sources Signal Texts in the Launch of Women’s and Gender Studies in Music 1979 o Catherine Clement, L’Opera ou la defaite des femmes The first feminist engagement with music under the umbrella of gender representation in opera, written by a psychoanalyst A signal work with major repercussions, including her influence on the American musicologist, Susan McClary 1981 o Eva Rieger, Frau, Musik & Mannerherrschaft First major feminist study of women and music, a very self-consciously political book, influenced by feminism and post-1968 politics 1986 o Jane M. Bowers and Judith Tick, eds., Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950 First major historical survey in English on women’s music A collection of essays from some of the leading scholars in the field Essays bring some major creators to the attention of discipline 1987 o Ellen Koskoff, ed., Women and Music in Cross-Cultural Perspective First major collection of essays in ethnomusicology which focuses on women’s roles in traditional musics 1990 o Susan McClary, Feminine Endings: Music, Gender and Sexuality First major feminist study in the U.S. engaging with both the general musical repertoire and contemporary women’s music Focuses on gender studies, keeps distance from historical work on women composers 1993 o Marcia J. Citron: Gender and the Musical Canon A study which engages not only with women musicians and their contributions to music history, but also asks questions about the exclusion of women from musicological and historical discourse Major monograph that explored the ideology of gender in women’s creations since the 19th century and its impact on the formation of the musical canon 1994 o Philip Brett, Elizabeth Wood and Gary C. Thomas, eds., Queering the Pitch: The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology (NY and London) First important collection of essays which brought gay and lesbian musicology into the main stream Developments in the Study of Women’s Music Since the 1970s 1. Making available women’s music The emergence of publishers and record companies dedicated to women’s music (ex. Furore Verlag) The publication of anthologies of women’s music. One of the earliest was the Historical Anthology of Music by Women, edited by James Briscoe (Bloomington, 1987), which came with a recording that allowed us to listen to music by women for the first time. Increasingly broader catalogue of recordings, especially when more and more scores became available With the edition of Louise Farrenc’s collected works, begun in 1982, the first female composer has received the same scholarly attention to her compositional work that is usually still reserved to male composers 2. The historical study of women’s music and biography Collections of essays were dedicated to women’s music The biographies of individual composers and performers are uncovered in articles and monographs Several dictionaries and databases dedicated to women musicians make names, dates, etc. available as a starting point into research Music in female institutions such as convents become the topic of scholarly studies Studies also focus on groups of performers (ex. Women pianists, women jazz players, women saxophone players, etc.) 3. Feminist Approaches to Women’s and Men’s Music In addition to the “compensatory” history of women’s music, scholars have engaged with critical approaches towards women’s music Approaches reach from sociological to anthropological enquiries, from cultural histories to feminist analysis of music. Topics embrace anything from sexually and gender performance to class and biography. Women and Music: Critical Perspectives 1. Major issues addressed in the “Introduction,” in Textbook need for an interpretation of materials about women’s musicmaking unearthed in historical and ethnographic enquiry this led to enquiries about social and cultural contexts: class, status and power of women 1980s introduces questions about the construction of gender and sexuality, in particular the binary construction of gender. Suzanne Cusick proposes to embrace an “eclectic multiplicity” (where inquiries into sexuality, race, ethnicity and class intersect with feminist musicology) 1990s bring focus on performance/performativity of gender in the context of music 2. Women’s Studies verses Gender Studies in music? The Difference Dilemma “The body of knowledge about women musicians has continued to grow and flourish, and its importance for the feminist goal of a fully representative music scholarship is immeasurable, but its relationship to what may be referred to as feminism proper varies with the degree to which each project makes use of interdisciplinary feminist theory and methods.” – Ruth A. Solie, “Feminism” “By 1990 women’s history in music had developed within three interlocking categories – repertory, social process and ideology… The process of integrating women’s history into mainstream narrative texts, and into the methodology of historiography itself, remains a profoundly important challenge. Nevertheless, the study of gender in music from various perspectives and through diverse approaches is now more widely countenanced.” – Judith Tick, “Women in Music” “Most persistently debated are the opposed feminist positions that have been taken with regard to “the difference dilemma’, a primarily strategic disagreement about whether the similarities between the sexes, or their differences, should underlie feminist argument. Put differently: since the category ‘women’ has been so burdened with historical and cultural resonance, as well as unjust laws and unfavorable material conditions, there is intense and continuing discussion of the extent to which it can be recuperated either for the celebration of achievement or for the exploration of women’s particular experience. An equally energetic argument asserts that the unitary category ‘women’ inappropriately obscures differences in race, class and other aspects of social identity which, like gender, distribute power and authority differently within different social contexts.” – Ruth A. Solie, “Feminism” Women’s Lives 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM Motherhood and Music Are women’s musical roles gender specific? In many societies, women and men do appear to occupy separate spheres, creating not necessarily two separate and self-contained music cultures, but rather two differentiated yet complementary halves of culture Reference to women’s music and musical practices are not uncommon in ethno-musicological literature When ethnographies focus on female initiation rites, birth, or child care, women’s musical activities associated with such events are frequently noted Music as an global expression Lullabies: Music is embedded in our memories from the earliest moments of childhood and is strongly connected to many moments – insignificant and important – in the life cycle Hearing a lullaby before sleep is one of the first musical experience Common features o Repetition: engaging to children since babies wake up to new sound; as a calming and soothing agent o Tight/narrow range of sound: not something to catch attention o Vocal: higher pitch as in baby talk; women solo; intimate o Lyric: teaches value in that society; or just nonsense syllables, the sound effects of the lullaby take precedence over meaning Bengali Lullaby: o Moderate pace, low volume, and extensive repetition with both instrumental and vocal parts o Refrain: recurring line o Interaction of the instruments: echoes and then repetitive o Ostinato: four-beat drum rhythm, descending melody, two strokes of the small brass bells; mimic the rocking motion o Culture representative o Soothing, not very fast o Repetitive o Complex lyrics o Flexible with multiple repetition Hebrew Lullaby o Only sung to baby girls o Identify origin and date o Feminine o Use of images: grape is perceived as feminine o Rhythm emphasized is unrelated to the word but the melody o Secular, no religious content o Only sing in private to sooth Kiowa Lullaby American Lullaby: “Hush, Little Baby” Summary o Flexible form o Rocking motion o In all societies, children are particularly attentive to the gestures and postures which, in their eyes, express everything that goes to make an accomplished adult – a way of walking, a tilt of the head, facial expressions, ways of sitting and of using implements, always associated with a tone of voice, a style of speech, and a certain subjective experience “Gender” is socially constructed opposed to “sex”. We inscribe different characteristics which overlap with our gender. “Feminine”: can be very problematic within contexts Men are not comfortable crying in public: gender construct Music can be powerful acting as a drive National Anthem at international events Music has to be regulated since it can be problematic when associated with different situations Lullabies can be soothing, but it would not fit into any sorrowful situation, like funerals. This is why we need laments. Women’s Lives 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM Women as mediators of grief Laments in Antiquity Women are considered the one who lament opposed to men are not supposed to. The assertion that weeping is for women does not merely express machismo in either its Spanish or its English sense; it is a cultural fact of the Mediterranean tradition, just one manifestation of the principle that the uninhibited expression of emotion belongs to women and not to men. In Greek tragedies, full-scale ‘monodies’ sung by individual characters are largely characteristic of women, above all in Euripides, the tragedian par excellence from his death till the Romantic era, whose female characters articulate emotions (and frequently in song) with a clarity that astounded his early audiences, but who never assigns a monody to a mature Greek male. The vivid representation of female emotion continued in Hellenistic literature, most notably in the passionate Medea of Appolonius’ Argonautica, one of Virgil’s models for his Dido, but also in laments put in the mouth of a women scorned or abandoned by the man she loves. – Leofranc Holford-Strevens As the voice of lament, women’s ritual chanting is ancient Greek society’s instrument for expressing sorrow at the deaths of kings and heroes in epic and for effecting the separation between the living and the dead that is one of the functions of funerary ritual. In both activities, it has a dangerous side and awakens ambivalence in the male-dominated society of early Greece, in part because women are associated with pollution, corruption, decay, and disorder. – Charles Segal The Sound of Lamenting Female lamenters often serve as intermediaries, making public the private grief of an individual. In so doing, they turn personal mourning into a communal experience. In some cultures, they take on magico-religious powers, where their musical performances act as a link between the living and the spiritual world of the dead. Though lament traditions vary widely around the world, they exhibit certain striking similarities in vocal expression and melodic construction. In many cases, the prominence of intermediary sounds, such as cries and wails, blur the boundaries between speech and song. More melodic than speech-like, the lament is punctuated with sobbing and shouts to express grief. Often the melody hovers within a limited range of a fifth or less. The songs generally consist of a series of improvised variations on a pattern of narrow melodic intervals that begin on a high pitch and cascade downwards three or four notes, as seen in the ritual wailing called sa-yalab sung by women of the Kaluli people in the rain forest of Papua, New Guinea. Uncovering Women’s Blues in Rural America During the early period of blues recordings, female vocalists like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith were active in urban areas, while singers recorded from the rural South were largely male. The perspective of rural blues is usually male, and when I asked James Thomas where blues comes from, he replied: ”Where they come from? They come from men, all I know.” - William Ferris Although many histories of the blues hardly mention the contribution of women, the music was central to their experience. If not in the fields, they often worked alone – … - and blues were the lullabies they sang, standards rooted in tribal memory, or songs as slow articulation of their own lives. Evidence of this is reflected in the recorded subject-matter of female blues artists – not only do they sing about their relationships, but they also use the domestic imagery of cooking (as Memphic Minnie’s ‘I’m Gonna Bake My Biscuits’) growing plants, making honey or keeping hens. Blues told their story just as accurately as it did that of a the male sharecropper. – Lucy O’Brien Since the early 1920s, there has been a fascination with black rural practices, especially the blues. The result is a vast literature that documents the early blues, mainly from the point of view of the southern black male experience. Only during the past decade has much attention been paid to female blues singers. Scholars have focused on the life experiences and songs of woman who sang the urban, classic blues in the 1920s and early 1930s. Through their readings of song texts, they have placed classic blues at the center of black feminism in early twentieth-century America. While these analyses provided depth and dimension to the blues discourse, there is still a facet of the blues tradition that scholars have ignored: the role women played in the antecedents of the classic blues, most specifically the rural blues tradition. – Kernodle Musical Structure of the Blues As the blues was created largely by musicians who had little education and scarcely any of whom could read music, improvisation, both verbal and musical, was an essential part of it, though not to the extent that it was in jazz. To facilitate improvisation a number of patterns evolved, of which the most familiar is the 12-bar blues. Apparently this form crystallized in the first decade of the 20th century as a three-line stanza in which the second line repeated the first, thus enabling the blues singer to improvise a third, rhyming ling while sing the second. This structure was supported by a fixed harmonic progression, which all blues performers knew: it consists of four bars on the tonic, of which two might accompany singing and the fourth might introduce a flattened seventh; two bars on the subdominant, usually accompanying singing, followed by two further bars on the tonic; two bars on the dominant seventh, accompanying the rhyming line of the vocal part; and two concluding bars on the tonic. Such a progression could be played in any key, though blues guitarists favored E or A and jazz musicians B. Many variants exist, but this pattern is so widely known that ‘playing the blues’ generally presupposes the use of it. – Paul Olivier Music Example from W.Africa West-African Yoruba Chorus o Expressiveness o Interactions between the drum and the vocal o Get-togethers Traditional West-African Folk Story Bessie Tucker: Rural Texas Blues Penitentiary The high-pitched opening moaning (holler tradition) that segues into the first phrase of the chorus The echoing of the vocal lines in the piano which begins to imitate rural guitar playing The increasingly improvisatory performance style of Tucker The shift in Tuckers performance in the last verse from moaning to a type of crying-singing Work with texts to express emotion, different stresses/emphasis Memphis Minnie: Rural Blues Becomes Classic Biography Hustling’ Woman’s Blues o Her own experience as a prostitute in the South Blues as Black Women’s Lament In 1930, Memphis Minnie recorded “Memphis Minnie-Jitis Blues,” which recalls her infection with bacterial meningitis and the substandard medical care more received. Despite the humorous pun in the title, the song tackles a tragic topic. Bacterial meningitis was fatal in the 1920s and 1930s, and lower classes in the ghettos were especially vulnerable to the disease. Strugglin’ Woman’s Blues – Clara Smith Outdoor Blues – Memphis Minnie Women’s Voices 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM Seduction and Sexuality Music are said to have magical powers: Women are constrained where, when and to whom they can perform Society pressure regulates Sirens Sirens feature in ancient legends throughout the world and have repeatedly been associated with the enchanting, inspirational and prophetic quality of music. Sirens are related also to knowledge, seduction and danger, most famously in Homer’s Odyssey. o Clog their ears o Tied to the pole o However, seduced when he heard the singing o By telling the story, we realize how powerful the music is As a result of the nineteenth century's fascination with sexuality, nature and culture, the siren became a trope for the alluring threat of female seduction, in particular the femme fatale. Countless paintings show beautiful women holding a lyre and singing. Their victims either are the spectator or painter lured into the scene, or are represented as doomed or already dead male bodies. It is not surprising that the mechanical sound that warns us from danger-the siren-takes the name of its female embodiment. Definitions of a Siren a woman-like creature who caused the wreck of ships and death of men by the use of their sweet singing and instrumental playing a dangerous beautiful woman Greek root meaning to bind or attach Something which makes a loud warning sound often found on police cars, ambulances and fire trucks Sirens are often associated with water. They don’t physically kill the men, rather lure them into extremely dangerous situations. Marilyn Monroe as Loreley Lee: An American Siren Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, with Jane Russell Soft voice, which would make “victims” more vulnerable Rather than doing the dance numbers, she sang with a more breathy voice Curtain: blue and sparkles, making the scene of water Dress: long slit and red sparkling, how sirens are portrayed in public culture Blonde Contrast from the other performers The Siren of “Lurley Rock” Loreley, the siren of the river Rhine, is rather young for a mythical creature. We even know her year of birth, 1802, and her genealogy as the main character in a long ballad by Clemens Brentano, included in his novel Godwi, which told the transformation out of betrayed love of a beautiful young fisherman's daughter into the sorceress Loreley. Loreley was named after the "Lurley" or "Lorle" mountain, a rock formation above the Rhine near Goarshausen, which had featured in various texts about the Rhine valley and its geography since the thirteenth century. The presence of a "spirit" in the rock was first mentioned in the early seventeenth century in Origines palatinae, and by the mideighteenth century, local folklore started gendering the spirit as female. The first literary text that turned the spirit into a woman and thus fixed the local narratives into a quickly and widely accepted pan-German legend was, however, Brentano's Lorelei ballad. Through it, the modern Rhine siren was born, and the landscape transformed into its female embodiment by naming the siren after the rock. Within a short span of time, Loreley became a widely appropriated legend, and her transformations—of which Marilyn Monroe's Lorelei Lee is but one of the more recent—provide a fascinating case-study of the cultural tropes involving the alluring but ultimately fatal seduction attributed to sirens in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Loreley: The German Siren The Loreley myth played an important role in forging of German national identity in the 19th century, particularly through Friedrich Silcher’s 1837 setting of Heinrich Heine’s Loreley. The strophic song in a lilting 6/8 barcarole rhythm was conceived as a melody in the folk-tone, appropriate for a poem that depicted an “old fairy tale.” Silcher’s version acquired the status of a popular national hymn, which travelled with immigrants to the shores of the U.S.A. and to the German colonies in S.W. Africa. The iconic power of the Silcher song becomes evident at the beginning of the 1979 TV drama Holocaust, when a wedding party, comprising a wide range of the political and religious strands of 1930s Germany, unites in singing. Loreley had become the symbol for German “Rheinromantik”, invoking patriotic nostalgia and nationalism. Representing Loreley An English Traveller Robert Schumann, 1840 Lied Music of poetry, transform music into lyrical Conversational Descriptive not only in words, but in the music o Riding horse, rhythmically decisive, sharp, o Excited when saw the women/siren o Seductive singing when singing in drawn-out style, hypnotizing Women’s Voices 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM Dance as a Female Voice in Japan Main issues in Text: Nihon buyo is a genre dominated by women, while kabuki remains an all-male genre While kabuki theater began with onna kabuki, women were banned from performing on kabuki stages in 1629. Public private Women studied dance and music o Geisha o Middle class studied as part of basic etiquette training o During the 18th century, wealthy merchant class studied in hope for employment in samurai households Traditions and embodiment of cultural knowledge o Concept of shifting sense of self What is nihon buyo? o A genre primarily based on a narrative o Dancers tell the story with their bodies; while a vocalist narrates the plot in song, including the voices of all the various characters o In some dance pieces, performers assume single role; in others, they take on multiple roles. Learning through example: Ame no shiki (Raining in the four seasons) o A male traveler encountering seasonal rains in Edo (Tokyo) o Numerous contrasting roles to illustrate his journey o Use of kimono supports character shifts Codeswitching: enculturated behavior and speech in Japan; mirrors a social coordination of self with clear among people o Shifting notions of self that are relational o Surface (omote) and inner (ura) self do not need to correspond o Shifting as “meta-level” knowledge about social relations and interactions o Codeswitching relies on shared modes of communication within a subculture Interpreting multiplicity in relation to notions of female self (fragmentation or empowerment). In the safe environment of dance lessons, role playing can offer an emotional outlet as well as an expanded vocabulary of identity. Ame no shiki Opening scene Entering, with three-stringed lute; very slow lyrical melody, male vocalist; masculine position, shielding his face from the rain with the fan as a straw hat Japanese music often indicates atmospheric changes. Rain stops: faster pulse, bells, flutes and drums, chorus singers. What he sees: birds, musicians, a mother with a child The mother with child: feminine movements; slower tempo, higher range, lilting melody Buddhist temple, candy peddler, four fruit peddlers Women’s Theatrical Embodiment of Male Characters in Other Cultures: Indrani: Kuchipudi Javanese: sword fight Giuditta Pasta in the role of the warrior Tancredi in Rossini’s eponymous opera Class Discussion Whose voice is it anyway? The singer’s voice or the listener’s? The author’s or the singer’s? To what extent do these voices embody and/or transgress the gender boundaries of their societies? Women’s Voices 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM Umm Kulthum, the Voice of Egypt We hear our own stories in her song. She is a vessel of her voice. She is a transmitter, at the same time, this is very gendered as women are the ones who give birth. Umm Kulthum became a powerful symbol, first of the aspirations of her country, Egypt, and then of the entire Arab world. Music Examples: El Hob Kollo (“All the Love”) o Music by Baligh Hamdy, who worked with Baligh from 1957 to 1974 Rich voice, authoritative performance Her voice and the music switch in domination Uses male pronoun in the text One big opponent was a male performer: traditional vs. modern (Western); had and sing-off, a concert with the two, and after two hours, she declared winning o Lyric by Ahmad Shafiq Amel, text is Egyptian Colloquial Al Atlal Virginia Danielson on Umm’s Impact Most famous singer in the 20th century Arab world Performed over 50 years, 1910 (wedding and special occasions with her father) to 1973 (her final illness) 300 songs, one of the first recording artists Monthly, she broadcasted her concert over radio waves, and became one of the first radio artists People gathered to listen to the broadcast When she died in 1975, her funeral was described as bigger than that of President Jamal ‘Abd al Nasir. She was the voice and face of Egypt From extracts Sang in universities, motivated the revolution in years following Even as a high class woman, she could blend in with students Her voice was super powerful and confident Never planned on becoming the “voice of Egypt”, but how she presented her music lead her into what has become Where does she come from? o Rural Egypt o Purity o Authenticity of traditional singing Professional Women 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM European Courtesans The tradition of the Courtesans Music in entertainment at royal court Institutionalized in many art traditions of Asia and N. Africa, and Europe, eg. Moorish Spain and 15th century Venice Powerful men restricted their own wives and daughters Women who are wives and daughters who were planned to be married were put aside from public performance, dancing or singing A small fraction of women from the lower socioeconomic class, or even slaves, were considered performers, courtesans, dancers, prostitution and so forth Women performing in public are not considered good women Using her voice as a method of seduction while performing in public Concerto delle Donne: Professionalization of the Female Musician Courtesan Concert of women Ferrara, N. Italy in the late 16th century: famous for music for about 100 years, splendid music, musical center Patrons: Alfonso and Margherita d’Este Aristocratic marriageable women played chamber music in the original concerti di donne at Ferrara, lower-born women has ambiguous status Object of Envy: The Concerto delle Donne. It complemented the "public" splendor of the court chapel with a sublime musical group to whose performances only selected members of the court and only specially chosen guests were admitted. Access to exclusive pleasure instead of more widely accessible festivities are the supreme distinction for a person at court. New musical group that performed in private apartments of the ruling couple Later on, the concerto delle donne was part of courtly life; every princely household had to have at least one Beginnings 1580 with one male singer (Giulio Cesare Bancaccio) and three women musicians (Laura, Anna, and Livia) The women appear in the court-rolls as ladies-in-waiting to the duchess Torquinia joined in 1583 These four women were brought in and paid richly by the court because of the beauty of their voices, and they sing regularly on demand Peverara, beautiful, virtue of singing, playing excellently, became the prima donna of the group Singers The Women singers o Upper middle class, artists or merchants o Musical education: talent and careers Laura Peverara o Mantuan merchant o Education for being groomed for courtly society Anna Guarini o Poet and court secretary Money o Musical education Tarquinia Molza o Poet o Educated o Poetess and singer Livia d’Arco o Minor Mantuan nobleman o Without a noble woman’s education o Two years of guidance before singing publicly Cesare Brancaccio o Hired as a musician, fired because he refused to sing once o Musica secreta Highly paid Brancaccio: 400 scudi per year, house, and horses Peverara: 300 scudi per year, married, house furnished Molza: 300 scudi per year, rooms Luzzasco Luzzaschi:135 scudi per year, rooms and a farm Music Madrigals: songs for several singers, often love poetry The Composer Luzzasco Luzzaschi o Singer at court o Organist and keyboard player o Musica secreta o Publish music after the death of the duke Music Examples Cantate ninfe o Repeated verses, top level singers, word emphasizing o Singing nymphs o Male singing started at second line o Sound mimic for joking and laughing, male voice missing, gender difference O dolvezz’ amarissime T’amo mia vita The imitators Northern Italy Composer, singer, courtesan? Barbara Strozzi, La Virtuossissima Cantatrice Biography Daughter of a poet Celebrated for her singing, published compositions, cultivated Suspect of prostitution, not a professional musician Compositions Le tre grazie a Venere o Consort of Musicke o Settings in her lyric o Turning the female body into a musical piece o Music are highly sexualized in Venice o Eroticize the piece o Writing her own music and her own poems Amor dormiglione Professional Women 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM India’s Public Dancers Nacnis Female dancers who perform in public Sexually active yet free, one of the rasikas is her partner Bound to her keeper by love and art Out-caste Associated with fertility Master of musical activities that are considered male Couples They are more integrated into the patriarchal world Mardana or Men’s Jhumar Gendered Drums with a clear and loud sound A duple division of the beat Bouncing and jumping Sexual allusions in texts Ex. Kistomani dancing mardana jhumar, musical gathering in Sanga Village Janani or Women’s Jhumar Without drums or softer and more diffuse sound Lilting triple subdivision Uniform Co-ordinated, swaying, hip-to-hip and in line Texts are about women Ex. Janani Jhumar at Brown University The voice of the Nacni Accommodations to the men’s style ultimately reconcile the gender difference Refashion her vocal technique, lower her range Hard to distinguish voices in singing The nacni along makes the accommodation, in effect capitulating to a man’s timbral world, following his lead. Pancpargania Style Rasika leads his nacni Link arms for long periods of time to enact their romantic union In Nagpuri style, a nacni daces independently Quiz Review Review Introduction History dates: overlap to the intro from book Developments since the 1970s Lullaby Laments: not very detailed Styles Sirens Marilyn Monroe Blondes Nihon Buyo Video Dance Props Code switching Ame no shiki Umm Kulthum Webpage Courtesan Concerto delle Donne Geishas Jhumar Gendered difference Social role of nacni Listening (2,10] 2 min top per piece name the piece while listening Cantate ninfe o Concerto delle Donne o Coming from the rural countryside o Natural Penitentiary o Bessie Tucker 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM o Field holler o Coming from Africa, AA women stick with their cultural heritage o 20th century Blues "Come O Sleep" Bengali Lullaby Dorothy Whitehorse Delauny "There's a little bunny swimming" Kiowa Lullaby Hebrew folksong "Hush now, go to sleep" Noumi, noumi, yaldati American folksong "Hush little Baby" Hush little Baby 1580 Luca Marenzio (1553–99): First Book of Madrigals, Cantate ninfe 1644 Barbara Strozzi First Book of Madrigals Le tre Grazie a Venere 1840 Robert Liederkreis op. 39. no. Schumann 3 Waldesgespräch (Conversation oin the Forest) 1928 Bessie Tucker: Penitentiary 1930 Memphis Minnie Memphis Minnie-Jitis Blues, 1950s Umm Kuthum "All the love," music by Baligh Hamdy, lyrics by El Hob Kolloh (extract) Ahmad Shafiq Amel. Short Answers and MC’s Be aware of multiple answers Marilyn Monroe o Breathy o Seductive o Siren o Costume o Stage décor Barbara Strozzi Sophie Drinker Eva Rieger Marcia Citron 1/12/2012 5:09:00 AM