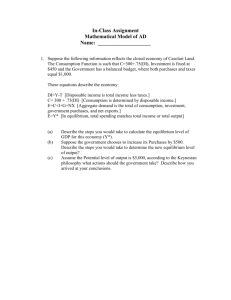

Chapter 12

Consumption,

Real GDP, and

the Multiplier

Copyright © 2012 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved.

Introduction

During the Great Recession of the late 2000s, inflation

adjusted spending on goods and services by U.S.

household declined by 2 percent, while the levels of

wealth, indebtedness and income of households fell

significantly.

Why and how was the decrease in U.S. consumption

spending related to the declines in household wealth,

debts and income?

Reading this chapter will help you answer this question.

Learning Objectives

• Distinguish between saving and savings and

explain how consumption and saving are

related

• Explain the key determinants of consumption

and saving in the Keynesian model

• Identify the primary determinants of planned

investment

Learning Objectives (cont'd)

• Describe how equilibrium real GDP is

established in the Keynesian model

• Evaluate why autonomous changes in total

planned expenditures have a multiplier effect

on equilibrium real GDP

• Understand the relationship between total

planned expenditures and the aggregate

demand curve

Chapter Outline

• Some Simplifying Assumptions in a Keynesian

Model

• Determinants of Planned Consumption and

Planned Saving

• Determinants of Investment

• Determining Equilibrium Real GDP

Chapter Outline (cont'd)

• Keynesian Equilibrium with Government and

the Foreign Sector Added

• The Multiplier

• How a Change in Real Autonomous Spending

Affects Real GDP When the Price Level Can

Change

• The Relationship Between Aggregate Demand

and the C + I + G + X Curve

Did You Know That ...

• At various times from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s,

the U.S. saving rate—the ratio of the flow of real, inflationadjusted saving to real GDP—was negative?

• In this chapter, you will learn how an understanding of

households’ real saving and real consumption spending can

help you evaluate fluctuations in a national’s real GDP.

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model

• To simplify the income determination model,

let’s assume:

1. Businesses pay no indirect taxes (sales tax)

2. Businesses distribute all profits to shareholders

3. There is no depreciation

4. The economy is closed; no foreign trade

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model (cont'd)

• Real Disposable Income

– Real GDP minus net taxes, or after-tax real income

• Consumption

– Spending on new goods and services out of a

household’s current income

– Whatever is not consumed is saved

– Consumption includes such things as buying food

and going to a concert

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model (cont'd)

• Saving

– The act of not consuming all of one’s current

income

– Whatever is not consumed out of spendable

income is, by definition, saved

– Saving is an action measured over time (a flow)

– Savings are a stock, an accumulation resulting

from the act of saving in the past

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model (cont'd)

• Consumption Goods

– Goods bought by households to use up, such as

food and movies

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model (cont'd)

• Accounting identity:

Consumption + saving disposable income

Saving disposable income – consumption

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model (cont'd)

• Investment

– Spending by businesses on things such as

machines and buildings, which can be used to

produce goods and services in the future

– The investment part of real GDP is the portion

that will be used in the process of producing

goods in the future

Some Simplifying Assumptions in a

Keynesian Model (cont'd)

• Capital Goods

– Producer durables; nonconsumable goods that

firms use to make other goods

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned

Saving

• In the classical model, the supply of saving

was determined by the rate of interest

– The higher the rate, the more people wanted to

save, and the less they wanted to consume

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Keynes argued that:

– The interest rate is not the most important

determinant of individual’s real saving and

consumption decisions

– Real saving and consumption decisions depend

primarily on a household’s real disposable income

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Keynes was concerned with changes in AD

AD = C + I + G + X

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Consumption Function

– The relationship between amount consumed and

disposable income

– A consumption function tells us how much people

plan to consume at various levels of disposable

income

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Dissaving

– Negative saving; a situation in which spending

exceeds income

– Dissaving can occur when a household is able to

borrow or use up existing assets

Table 12-1 Real Consumption and Saving Schedules: A

Hypothetical Case

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• 45-Degree Reference Line

– The line along which planned real expenditures

equal real GDP per year

Figure 12-1

The Consumption and

Saving Functions

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Autonomous Consumption

– The part of consumption that is independent of

the level of disposable income

– Changes in autonomous consumption shift the

consumption function

Policy Example: Why Knowing Consumer Sentiment Aids

Consumption Forecasts

• Government economists use the University of Michigan’s

Index of Consumer Sentiment to help forecast total U.S.

consumption spending over the coming weeks and months.

• That Index is based on answers to questions about how

confident people are about their future disposable income.

• Household’s confidence about future disposable income

affects their autonomous consumption.

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Average Propensity to Consume (APC)

– Real consumption divided by real disposable

income

– The proportion of total disposable income that is

consumed

Real consumption

APC =

Real disposable income

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Average Propensity to Save (APS)

– Real saving divided by real disposable income (DI)

– Saved proportion of real DI

Real saving

APS =

Real disposable income

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC)

– The ratio of the change in real consumption to the

change in real disposable income

MPC =

Change in real consumption

Change in real disposable income

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS)

– The ratio of the change in saving to the change in

disposable income

MPS =

Change in real saving

Change in real disposable income

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Example

– Income = $54,000

– C = $49,200

– S = $4,800

• What is the APC?

APC =

$49,200

= .911

$54,000

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Example

– Income increases by $6,000 to $60,000

– C = $54,000

– S = $6,000

• What is the APC?

APC =

$54,000

= .90

$60,000

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Some relationships

APC + APS 1

MPC + MPS 1

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Causes of shifts in the consumption function

– A change besides real disposable income will

cause the consumption function to shift

– Non-income determinants of consumption

• Population

• Wealth

Determinants of Planned Consumption and Planned Saving

(cont'd)

• Net wealth

– The stock of assets owned by a person,

household, firm or nation (net of any debts owed)

– For a household, wealth can consist of a house,

cars, personal belongings, stocks, bonds, bank

accounts, and cash (minus any debts owed)

Why Not … help the economy by taking from the rich and

giving to the poor?

• Redistributing wealth from high-income households to lowerincome households would cause the autonomous

consumption of lower-income households to rise but the

autonomous consumption of high-income households to fall.

• On net, total household wealth would be unaffected by the

redistribution and thus aggregate autonomous consumption

would be almost unchanged.

Determinants of Investment

• Investment, you will remember, consists of

expenditures on new buildings and equipment

– Gross private domestic investment has been

volatile

– Consider the planned investment function, and

shifts in the function

Figure 12-2 Planned Real Investment,

Panel (a)

Figure 12-2 Planned Real Investment,

Panel (b)

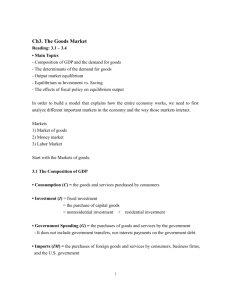

Determining Equilibrium Real GDP

• We are interested in determining the

equilibrium level of real GDP per year

– Consumption as a function of real GDP

– The 45-degree reference line

Figure 12-3 Consumption as a

Function of Real GDP

Determining Equilibrium Real GDP

(cont'd)

• Adding the investment function

AD = C + I + G + X

Figure 12-4 Combining Consumption

and Investment

Determining Equilibrium Real GDP

(cont'd)

• Saving and investment: planned versus actual

– Only at equilibrium real GDP will planned saving

equal actual saving

– Planned investment equals actual investment

– Hence planned saving is equal to planned

investment

Figure 12-5 Planned and Actual Rates

of Saving and Investment

Determining Equilibrium Real GDP

(cont'd)

• Unplanned increases in business inventories

– Consumers purchase fewer goods and services

than anticipated

– This leaves firms with unsold products and

inventories will rise

– Businesses respond by cutting back production

and reducing employment

Determining Equilibrium Real GDP

(cont'd)

• Unplanned decreases in business inventories

– Business will increase production of goods and

services and increase employment

– Ultimately there will be an increase in real GDP

Example: A Great Inventory Buildup During the Great Recession

• For 10 months following the officially designated start of the

Great Recession in December 2007, business inventories

shrank as U.S. firms managed inventories at relatively low

levels.

• During the last few weeks of 2008, however, unsold business

inventories suddenly jumped by nearly $70 billion because of

a decline in household spending by a similar amount.

Keynesian Equilibrium with Government and the Foreign

Sector Added

• To this point we have ignored the role of

government in our model

• We also left out the foreign sector of the

economy in our model

• Let’s think about what happens when we add

these elements

Keynesian Equilibrium with Government and the Foreign

Sector Added (cont'd)

• Government (G): C + I + G

– Federal, state, and local

• Does not include transfer payments

• Is autonomous

• Lump-sum taxes = G

• Lump-Sum Tax

– A tax that does not depend on income or the

circumstances of the taxpayer

Keynesian Equilibrium with Government and the Foreign

Sector Added (cont'd)

• The Foreign Sector: C + I + G + X

– Net exports (X) equals exports minus imports

– Depends on international economic conditions

– Autonomous—independent of real national

income

Table 12-2 The Determination of Equilibrium Real GDP with

Government and Net Exports Added

Keynesian Equilibrium with Government and the Foreign Sector

Added (cont'd)

• Determining the equilibrium level of GDP per

year

– We are now in a position to determine the

equilibrium level of real GDP per year

– Remember that equilibrium always occurs when

total planned real expenditures equal real GDP

Figure 12-6 The Equilibrium Level of Real GDP

Keynesian Equilibrium with Government and the Foreign

Sector Added (cont'd)

The Equilibrium Level of Real GDP

• Observations

– If C + I + G + X = Y

• Equilibrium GDP

– If C + I + G + X > Y

• Unplanned decrease in inventories

• Businesses raise output

• Y returns to equilibrium

– If C + I + G + X < Y

• Unplanned increase in inventories

• Businesses reduce output

• Y returns to equilibrium

The Multiplier

• Multiplier

– The ratio of the change in the equilibrium level of

real national income to the change in autonomous

expenditures

– The number by which a change in autonomous

real investment or autonomous real consumption

is multiplied to get the change in equilibrium real

GDP

The Multiplier (cont'd)

• Question

– How can a $100 billion increase in investment

generate a $500 billion increase in equilibrium real

GDP?

• Answer

– The multiplier process

Table 12-3 The Multiplier Process

The Multiplier (cont'd)

• The multiplier formula

1

1

Multiplier =

=

1 - MPC

MPS

The Multiplier (cont'd)

• By taking a few numerical examples, you can

demonstrate to yourself an important

property of the multiplier

– The smaller the MPS, the larger the multiplier

– The larger the MPC, the larger the multiplier

The Multiplier (cont'd)

• Examples

MPC =

4

5

MPS =

1

5

Multiplier =

1

=5

1/5

MPC =

3

5

MPS =

2

5

Multiplier =

1

= 2.5

2/5

The Multiplier (cont'd)

• Measuring the change in equilibrium income

from a change in autonomous spending

Change in equilibrium real GDP =

Multiplier x Change in autonomous spending

The Multiplier (cont'd)

• Significance of the multiplier

– It is possible that a relatively small change in

consumption or investment can trigger a much

larger change in real GDP

How a Change in Real Autonomous Spending Affects Real GDP

When

the Price Level Can Change

• So far our examination of how changes in real autonomous

spending affects equilibrium real GDP has considered a

situation in which the price level remains unchanged

• Our equilibrium analysis has only considered how AD shifts in

response to investment, government spending, net exports

How a Change in Real Autonomous Spending Affects Real

GDP When the Price Level Can Change (cont'd)

• When we take into account the aggregate supply curve, we

must also consider responses of the equilibrium price level to

a multiplier-induced change in AD

Figure 12-7 Effect of a Rise in Autonomous Spending on

Equilibrium Real GDP

The Relationship Between Aggregate Demand and the

C + I + G + X Curve

• Aggregate demand consists of:

– Consumption

– Investment

– Government

– Foreign sector

The Relationship Between Aggregate Demand and the C + I

+ G + X Curve (cont'd)

• There is a major difference between the two:

– C + I + G + X curve drawn with price level constant

– AD curve drawn with the price level changing

• To derive the aggregate demand curve from

the C + I + G + X curve, we must now allow the

price level to change

The Relationship Between Aggregate Demand and the C + I

+ G + X Curve (cont'd)

• What are some of the effects of a price level

increase?

– Real balance effect

– Interest rate effect

– The open economy effect

Figure 12-8

The Relationship

Between AD and the C +

I + G + X Curve

You Are There: In Boise, Idaho, Inventories Accumulate as

Desired Saving Rises

• In the late 2008 and early 2009, Noreen and Rick Capp of

Boise, Idaho, began to consume less and save more in order to

pay off their credit card debt.

• The decisions of the Capps and other Boise families to increase

planned saving were transmitted to businesses as unplanned

inventory buildups.

Issues & Applications: Why U.S. Consumption Spending Dropped in the

Late 2000s

• Between the end of 2007 and mid-2009, aggregate U.S. real

consumption spending declined by about $175 billion.

• Figure 12-9 shows that declines in real disposable income and

real household wealth led to a drop in real consumption

expenditures.

Figure 12-9 Real Household Debt, Housing Wealth, Disposable

Income, and Stock Wealth Indexes Since 1960

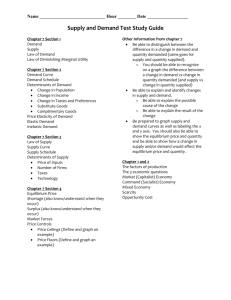

Summary Discussion of Learning

Objectives

• The difference between saving and savings

and the relationship between saving and

consumption

– Saving is a flow over time while savings is a stock

– Consumption plus saving equals disposable

income

Summary Discussion of Learning

Objectives (cont'd)

• Key determinants of consumption and saving

in the Keynesian model

– In the classical model, the interest rate is the

fundamental determinant of saving

– In the Keynesian model, the primary determinant

is disposable income

– DI increases, so does C

Summary Discussion of Learning

Objectives (cont'd)

• The key determinants of planned investment

– The interest rate, business expectations,

productive technology, and business taxes

Summary Discussion of Learning

Objectives (cont'd)

• How equilibrium real GDP is established in the

Keynesian model

– Equilibrium national income occurs where the C +

I + G + X schedule crosses the 45-degree line

Summary Discussion of Learning

Objectives (cont'd)

• Why autonomous changes in total planned

expenditures have a multiplier effect on

equilibrium real GDP

– As consumption increases, so does real GDP,

which induces further consumption spending

– The ultimate expansion of real GDP is equal to

the multiplier times the increase in autonomous

expenditures

Summary Discussion of Learning

Objectives (cont'd)

• The relationship between total planned

expenditures and the aggregate demand curve

– AD consists of consumption, investment, and

government purchases, plus the foreign sector

– Difference

• C + I + G + X curve drawn with price level constant

• AD with the price level changing

Figure C-1 Graphing the Multiplier