Principles of dualism

Cognitive Computing

2012

The computer and the mind

DUALISM

Professor Mark Bishop

On metaphysics

The Cognitive Computing MSC is not a philosophy degree ..

.. however, as basic philosophical notions infuse cognitive science, some familiarity with a few basic concepts from philosophy is essential.

Metaphysics is not – as is commonly thought – the “science of the immaterial ”.

In philosophy metaphysics is concerned with examining the fundamental nature of “being and the world”.

In metaphysics the different kinds [or ways] of being are called

“ categories of being ”, or simply categories .

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 2

On ontology

Ontology fundamentally concerns the “study of being and existence ”.

Ontology enquires if some ‘categories of being’ are fundamental.

and, if so, in what sense the items in those categories can be said to “be”.

Ontology is the inquiry into being in so much as it is being ( “being qua being ”) or into beings insofar as they exist (“being qua existence ”) and not the particular facts that can be obtained about “beings insofar as they exist ” them or the particular properties of them.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 3

Dualism

Dualism was an early metaphysical attempt to provide answers to questions of the form:

What kind of thing is mind (if anything)?

How is the mind (the mental) related to the body and the world?

What characterizes the mental?

Most generally, dualism expresses the view that, ‘ reality consists of two fundamentally disparate parts ’.

More specifically in the philosophy of mind it is the belief that, “the mental and physical are ontologically distinct ” (fundamentally different in kind; different categories of being);

thus the mental is [at very least] not identical with the physical.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 4

Causation and dualism

Interactionist dualism

Mental phenomena and material entities comprise two distinct ‘categories of being’;

Each can have causal effects on the other.

Epiphenomenal dualism

Mental phenomena and material entities comprise two distinct ‘categories of being’;

But ‘mental phenomena’ do not cause material effects

- despite widespread belief that they appear to.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 5

Types of dualism

Substance dualism (from Descartes)

The view that the mental and the physical are ontologically distinct :

The mental and the physical comprise two different categories of being: mind-stuff and body-stuff.

Property dualism

The view that the mental and the physical comprise two fundamentally distinct ‘ classes of property ’ that are coinstantiated in the same objects (e.g. brains).

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 6

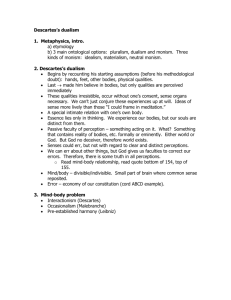

Substance dualism (1)

Mind-stuff and body-stuff are two categories of being:

‘ Res cogitans ’ : an immaterial substance without spatial dimensions whose essence is to think.

‘ Res extensa ’ : a physical substance that has extension and location in space. It is incapable of thought. Its essence is ‘to fill space’.

Hence the perceiving subject is ontologically distinct (and separated) from the perceived object. I.e. Mental items represent things, ‘distinct from themselves’.

Perception, in contrast to naïve realism, is thus indirect ; the mind access representation of things not the things in themself.

The brain (res extensa) sends signals to mind (res cogitans) which invokes the

‘mental items’ used in perception and cognition.

Conversely ‘mental items’ can invoke brain states which translate to motor events.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 7

Dualism as a ‘representational theory of mind ’

In representational theories of mind cognitive states are relations to mental representations which have content .

A ‘cognitive state’ is a state (of mind) denoting knowledge; understanding; belief etc.

‘ Cognitive processes ’ are mental operations on mental representations .

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 8

Substance dualism: the argument from skeptical doubt

“Mind or any mental state could exist whether or not (and however) any bodies (material things) exist ”

See Descartes ’ Second Meditation, “ Cogito, ergo sum ”

I can doubt that the material human being Mark Bishop exists.

Descartes and the evil demon…

But I cannot doubt that I exist.

… I cannot doubt that I am doubting.

Therefore it is possible that ‘I’ could exist and the ‘material human being Mark Bishop ’ not exist.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 9

Substance dualism: the argument from clear and distinct ideas

I can ‘clearly and distinctly’ perceive the mind apart from the body.

Therefore ‘the mind’ and ‘the body’ must be distinct.

But are we really aware of everything in ones mind (all the mind stuff) or in ones body (all the body stuff)?

If not, how can we be sure we ‘ clearly and distinctly ’ perceive the mind apart from the body?

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 10

Substance dualism: the argument from divisibility

Matter (e.g. my body) is divisible ;

it must be as it is extended in space.

The mind is NOT divisible ; it is a ‘ category mistake ’ to apply the property of ‘divisibility’ to ‘mental properties’.

A category mistake, or category error is a semantic or ontological error by which a property is ascribed to a thing that could not possibly have that property, (Ryle, G, (1949), ‘The Concept of Mind’).

Therefore the mind is not material!

But is it a ‘category mistake’ to consider splitting the mind in two?

It is certainly at least conceivable to envisage two half-minds (split temporally or by content) each containing half of all experience and knowledge..

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 11

The causal interaction argument against substance dualism

Casual Interaction: we need a plausible account of the interaction between mind & body.

Any adequate metaphysics of human beings as a union of two things (mind

+ body) must provide a plausible account of their interaction.

A-priori substance dualism entails that ‘mental substance’ has no properties in common with ‘physical substance’.

‘Acts of thinking’ need no material thing to have them.

‘Acts of thinking’ need none of the properties of material things: spatial extension, position etc.

Yet causation entails at least some similarity between cause & effect.

Hence SD cannot account for causal interaction and hence does not provide an adequate metaphysics of mind.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 12

Property dualism

The view that the mental and the physical comprise two different

‘classes of property’ that are co-instantiated in the same objects (e.g. brains).

One aspect of mind is material;

as it is instantiated by the brain and

‘the world’ constitutes the ‘mental properties’ of the brain.

But another aspect of mind ‘ mental properties ’ - are non-physical:

Mental properties are in some sense emergent on brain states;

And co-occurrent with

‘brain properties’.

However we can never simply reduce ‘mental properties’ to ‘brain properties ’.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 13

On the ‘ wetness of water ’

An analogy to the ‘property dualism of the mental ’ is the phenomenal feel of ‘the wetness of water ’.

The wetness of water is real and co-occurrent with specific properties of hydrogen & water.

However we can ’t reduce the ‘wetness of water’ to the physical properties of hydrogen & oxygen;

Contrast the ‘hardness of diamond’ which can be deduced from the physical properties of carbon molecules.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 14

Property dualism: the argument from reduction

Brain states are material and casually linked to subjective experience.

But subjective experience {e.g. the wetness of water} cannot be deduced from, reduced to, or identified with, brain states

as brain states have irreducibly material not mental properties

{e.g. ‘hydrogen and oxygen’ and ‘the wetness of water’}.

Hence mental properties are not reducible to material properties.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 15

Property dualism: the argument from introspection

1.

The mental contents of subjective experiences are knowable to me by introspection.

2.

‘Properties of my brain states’ are not knowable to me be introspection.

3.

Hence the mental contents of subjective experiences are not properties of brain states.

But does [2] presupposes what [3] is meant to establish;

‘begging the question’?

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 16

Property dualism: the argument from knowledge

Frank Jackson - The ‘ epistemic argument ’ Mary the colour blind neuroscientist ..

Suppose Mary knows everything about brain states and their properties, (there exists a ‘complete neuroscience’).

Suppose Mary doesn ‘t know everything about sensations and their properties, (she has lived all her life in a grey room), but she has read up all about the brain states of seeing, say, a red tomato, (though she doesn ‘t know what it is like to SEE a red tomato).

Hence sensations (& their properties) are not reducible to brain states (& their properties).

i.e. Psychology cannot be reduced to neuroscience.

10/04/2020 (c) Bishop: An introduction to Cognitive Science 17