EDWARD VI - CLIO History Journal

advertisement

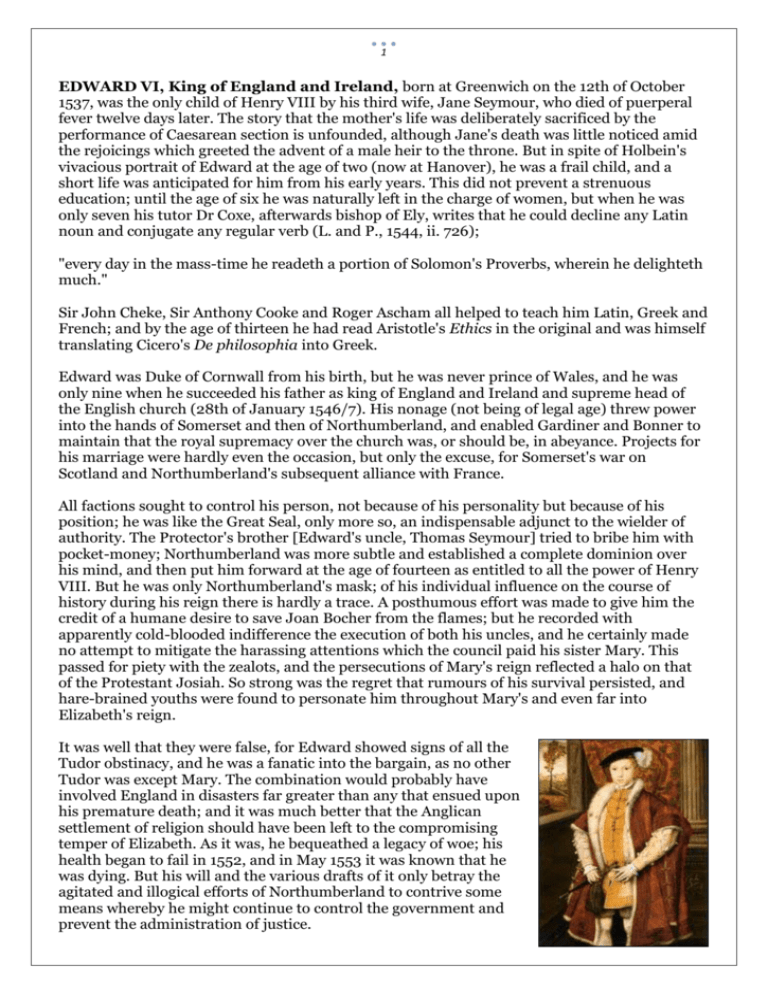

1 EDWARD VI, King of England and Ireland, born at Greenwich on the 12th of October 1537, was the only child of Henry VIII by his third wife, Jane Seymour, who died of puerperal fever twelve days later. The story that the mother's life was deliberately sacrificed by the performance of Caesarean section is unfounded, although Jane's death was little noticed amid the rejoicings which greeted the advent of a male heir to the throne. But in spite of Holbein's vivacious portrait of Edward at the age of two (now at Hanover), he was a frail child, and a short life was anticipated for him from his early years. This did not prevent a strenuous education; until the age of six he was naturally left in the charge of women, but when he was only seven his tutor Dr Coxe, afterwards bishop of Ely, writes that he could decline any Latin noun and conjugate any regular verb (L. and P., 1544, ii. 726); "every day in the mass-time he readeth a portion of Solomon's Proverbs, wherein he delighteth much." Sir John Cheke, Sir Anthony Cooke and Roger Ascham all helped to teach him Latin, Greek and French; and by the age of thirteen he had read Aristotle's Ethics in the original and was himself translating Cicero's De philosophia into Greek. Edward was Duke of Cornwall from his birth, but he was never prince of Wales, and he was only nine when he succeeded his father as king of England and Ireland and supreme head of the English church (28th of January 1546/7). His nonage (not being of legal age) threw power into the hands of Somerset and then of Northumberland, and enabled Gardiner and Bonner to maintain that the royal supremacy over the church was, or should be, in abeyance. Projects for his marriage were hardly even the occasion, but only the excuse, for Somerset's war on Scotland and Northumberland's subsequent alliance with France. All factions sought to control his person, not because of his personality but because of his position; he was like the Great Seal, only more so, an indispensable adjunct to the wielder of authority. The Protector's brother [Edward's uncle, Thomas Seymour] tried to bribe him with pocket-money; Northumberland was more subtle and established a complete dominion over his mind, and then put him forward at the age of fourteen as entitled to all the power of Henry VIII. But he was only Northumberland's mask; of his individual influence on the course of history during his reign there is hardly a trace. A posthumous effort was made to give him the credit of a humane desire to save Joan Bocher from the flames; but he recorded with apparently cold-blooded indifference the execution of both his uncles, and he certainly made no attempt to mitigate the harassing attentions which the council paid his sister Mary. This passed for piety with the zealots, and the persecutions of Mary's reign reflected a halo on that of the Protestant Josiah. So strong was the regret that rumours of his survival persisted, and hare-brained youths were found to personate him throughout Mary's and even far into Elizabeth's reign. It was well that they were false, for Edward showed signs of all the Tudor obstinacy, and he was a fanatic into the bargain, as no other Tudor was except Mary. The combination would probably have involved England in disasters far greater than any that ensued upon his premature death; and it was much better that the Anglican settlement of religion should have been left to the compromising temper of Elizabeth. As it was, he bequeathed a legacy of woe; his health began to fail in 1552, and in May 1553 it was known that he was dying. But his will and the various drafts of it only betray the agitated and illogical efforts of Northumberland to contrive some means whereby he might continue to control the government and prevent the administration of justice. 2 Mary and Elizabeth were to be excluded from the throne, as not sufficiently pliant instruments; Mary Stuart was ignored as being under Scottish, Catholic and French influence; the duchess of Suffolk, Lady Jane Grey's mother, was excluded because she was married, and the duke her husband might claim the crown matrimonial. In fact, all females were excluded, except Jane, on the ground that no woman could reign; even she was excluded in the first draft, and the crown was left to "the Lady Jane's heirs male." But this draft was manipulated so as to read "the Lady Jane and her heirs male." That Edward himself was responsible for these delirious provisions is improbable. But he had been so impregnated with the divine right of kings and the divine truth of Protestantism that he thought he was entitled and bound to override the succession as established by law and exclude a Catholic from the throne; and his last recorded words were vehement injunctions to Cranmer to sign the will. He died at Greenwich on the 6th of July 1553, and was buried in Henry VII's chapel by Cranmer with Protestant rites on the 8th of August, while Mary had Mass said for his soul in the Tower. Above excerpted from: Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol VIII Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 997. Edward VI became king at the age of nine upon the death of his father, Henry VIII, and a Regency was created. Although he was intellectually precocious (fluent in Greek and Latin, he kept a full journal of his reign), he was not, however, physically robust. His short reign was dominated by nobles using the Regency to strengthen their own positions. The King's Council, previously dominated by Henry, succumbed to existing factionalism. On Henry's death, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford and soon to be Duke of Somerset, the new King's eldest uncle, became Protector. Seymour was an able soldier; he led a punitive expedition against the Scots, for their failure to fulfil their promise to betroth Mary, Queen of Scots to Edward, which led to Seymour's victory at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547 - although he failed to follow this up with satisfactory peace terms. During Edward's reign, the Church of England became more explicitly Protestant - Edward himself was fiercely so. The Book of Common Prayer was introduced in 1549, aspects of Roman Catholic practices (including statues and stained glass) were eradicated and the marriage of clergy allowed. The imposition of the Prayer Book (which replaced Latin services with English) led to rebellions in Cornwall and Devon. 3 Despite his military ability, Seymour was too liberal to deal effectively with Kett's rebellion against land enclosures in Norfolk. Seymour was left isolated in the Council and the Duke of Northumberland subsequently overthrew him in 1551. Seymour was executed in 1552, an event which was only briefly mentioned by Edward in his diary: 'Today, the Duke of Somerset had his head cut off on Tower Hill.' Northumberland took greater trouble to charm and influence Edward; his powerful position as Lord President of the Council was based on his personal ascendancy over the King. However, the young king was ailing. Northumberland hurriedly married his son Lord Guilford Dudley to Lady Jane Grey, one of Henry VIII's great-nieces and a claimant to the throne. Edward accepted Jane as his heir and, on his death from tuberculosis in 1553, Jane assumed the throne. http://www.royal.gov.uk/historyofthemonarchy/kingsandqueensofengland/thetudors/edwardvi.aspx In the first journal entry to the right Edward VI records the results of an unsuccessful war in Scotland, civil disturbances in England and the execution of the Protector's brother who was also the king's uncle. It ends with the Protector's fall from power. In the second journal entry Edward discusses a religious dispute with his older half-sister Princess Mary. She was under renewed pressure to end the illegal Mass in her household. 1549 In the meantime in England rose great stirs, likely to increase much if it had not been well foreseen. The council, about nineteen of them, were gathered in London, thinking to meet with the Lord Protector and to make him amend some of his disorders. He, fearing his position, caused the secretary in my name to be sent to the lords to know for what cause they gathered their powers together and, if they meant to talk with him, to say that they should come in a peaceable manner. The next morning, being 6 October and Saturday, he commanded the armour to be brought out of the armoury of Hampton Court, about 500 harnesses, to arm both his and my men with it, the gates of the house to be fortified, and people to be raised. People came abundantly to the house. That night with all the people at nine or ten o'clock at night I went to Windsor, and there watch and ward was kept every night. The lords sat in the open places of London, calling gentlemen before them and declaring the causes of accusing the lord protector, and caused the same to be proclaimed. After which time few came to Windsor, but only the men of my own guard who the lords willed, fearing the rage of the people so lately quieted. Then the protector began to treat by letters, 4 sending Sir Philip Hoby, lately come from his embassy in Flanders to see his family, who brought on his return a very gentle letter to the protector which he delivered to him, another to me, another to my household, to declare his faults, ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars in my youth, negligence about Newhaven, enriching himself from my treasure, following his own opinions, and doing all by his own authority etc., which letters were openly read, and immediately the lords came to Windsor, took him and brought him through Holborn to the Tower. Afterwards I came to Hampton Court where they appointed by my consent six lords of the council to be attendant on me, at least two, and four knights. Lords - the marquis of Northampton, the earls of Warwick and Arundel, lords Russell, Sr John and Wentworth. Knights - Sir Andrew Dudley, Sir Edward Rogers, Sir Thomas Darcy, Sir Thomas Wroth. Afterwards I came through London to Westminster. Lord Warwick was made admiral of England. Sir Thomas Cheney was sent to the emperor for relief, which he could not obtain. Mr Nicholas Wootton was made secretary. The lord protector, by his own agreement and submission, lost his protectorship, treasureship, marshalship, all his movables and nearly 2,000 pds of lands, by act of Parliament. 1551 The lady Mary, my sister, came to me to Westminster, where after greetings she was called with my council into a chamber where it was declared how long I had suffered her mass, in hope of her reconciliation, and how now, there being no hope as I saw by her letters, unless I saw some speedy amendment I could not bear it. She answered that her soul was God's and her faith she would not change, nor hide her opinion with dissembled doings. It was said I did not constrain her faith but willed her only as a subject to obey. And that her example might lead to too much inconvenience. On 19 March the emperor's ambassador came with a short message from his master of threatened war, if I would not allow his cousin the princess to use her mass. No answer was given to this at the time. The following day the bishops of Canterbury, London and Rochester, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley and John Scory, concluded that to give licence to sin was sin; to allow and wink at it for a time might be born as long as all possible haste was used. http://englishhistory.net/tudor/ed1.html