Bone Formation, Growth, Remodeling Repair of Bone

advertisement

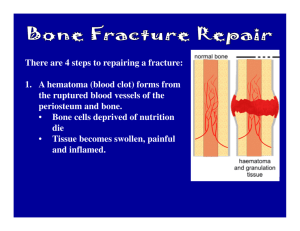

Bone Formation, Growth, Remodeling Repair of Bone Fractures Page 121 to 124 Connective Tissues Cartilage Embryos: hyaline cartilage Young child: cartilage replaced by bone except bridge of nose, parts of ribs, and joints. Bone Ossification: bone formation Bone Formation Hyaline cartilage is covered with bone matrix by osteoblasts (bone forming cells). The enclosed hyaline cartilage is digested away, opening up a medullary cavity within the newly formed bone. Bone Formation By birth, most hyaline cartilage have been converted to bone except for two regions Articular cartilages Epiphyseal plates Articular Cartilage Persist for life. Reduces friction at the joint surfaces. Epiphyseal plates Provide longitudinal growth of the long bones during childhood. Growth controlled by growth hormones and sex hormones (during puberty). Completely converted to bone during adolescence. Bone is an active tissue. Responds to calcium levels. Pull of gravity and muscles. Calcium Levels Decrease parathyroid hormones (PTH) are released Activates osteoclasts (giant bone-destroying cells. Increase (hypercalcemia) Calcium from the blood is deposited in the bone matrix as hard calcium salts. May cause renal or bladder stones May be a sign of other diseases Pull of gravity and muscles Bones where bulky muscles are attached become thicker and form large projections. Inactivity causes loss of mass and atrophy in bones due to lack of stress. Repair of Bone Fractures Hematoma (blood-filled swelling) is formed. The break is splinted by a fibrocartilage callus (mass of repair tissue). The bony callus (made of spongy bone) is formed. Bony callus is remodeled in response to the mechanical stresses placed on it, so that it forms a strong permanent “patch” at the fracture site.