Frank_for-distribution - The Institute on Medicine as a Profession

advertisement

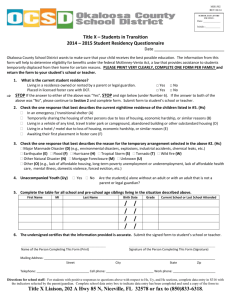

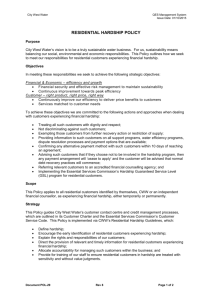

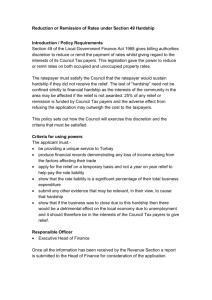

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE AS A PROFESSION: Physician Advocacy Conference November 18-19, 2010 Dr. Deborah A. Frank Professor of Pediatrics, Boston University School of Medicine Founder and Principal Investigator, Children’s HealthWatch Founder and Director, Grow Clinic for Children, Boston Medical Center WE SIT BESIDE THE GIANTS ON WHOSE SHOULDERS WE STAND How Did I Get Here? 3 4 You were Either Hospital or Orphanage 5 6 7 How Did I Get Here? 8 Riding Two Advocacy Horses 9 Trouble with Women is They Take Everything Personally! Children’s HealthWatch Collect data in five urban, safety-net hospitals Produce scientific research that is original and timely Share evidence with state and national partners to inform policy choices Children’s HealthWatch • • • • • • • • • • • • • Deborah A. Frank, MD (Boston) Maureen Black, PhD (Baltimore) John Cook, PhD (Boston) Mariana Chilton, PhD (Philadelphia) Carol Berkowitz, MD (Los Angeles) Patrick Casey, MD, MPH (Little Rock) Diana Cutts, MD (Minneapolis) Alan Meyers, MD, MPH (Boston) Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, MPH (Boston) Timothy Heeren, PhD (Boston) Sharon Coleman MPH (Boston) Megan Sandel MD (Boston) Zhaoyan Yang, MS (Boston) Why Watch Children Birth to 3? Official Poverty Rates by Age Group 25% 22% 20% 18% 14% 15% 10% 5% 0% Chi l dr en Under A ge 6 Chi l dr en A ge 6 or Ol der A dul t s 18-64 Data Supports Sensitive Period Hypothesis Sensitive Period Hypothesis: Insult during brain growth spurt most likely to be irreversible Poverty in early childhood has more severe and lasting effects on later health, cognition, and behavior than poverty at later ages (Duncan,Ziol-Guest,Kalil, Child Development,2010) Food Insecurity Limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways Source: USDA Help Connect the Dots 18 FOOD INSECURITY, HUNGER, AND MALNUTRITION ARE ALL – – – – – – Child Health Issues Adult Health Issues Mental Health Issues Educational Issues Political Issues Moral Issues 19 CHANGES IN FAMILY SURVIVAL RESOURCES RAPIDLY REFLECTED IN HEALTH, LEARNING, AND GROWTH OF YOUNG CHILDREN 20 The Problem to Address: Food Insecurity: Highest Since 1995 Overall, households with children (<18) had nearly twice the rate of food insecurity (21.3 percent) as those without children (11.3 percent). Families with the youngest children are most at risk for food insecurity. 25.4 percent of households with children under six are food insecure in the U.S. That translates to 9, 647. 000 American kindergarteners, preschoolers, toddlers, and infants. (USDA data,2009) Puzzle of Poverty and Obesity • Cyclical food deprivation/overeating • Need to minimize per calorie cost • Lack of access to fruits and vegetables in low income neighborhoods • Lack of opportunity for safe exercise in low income neighborhoods • ? Stress hormones Real Cost of a Healthy Diet Can parents afford to purchase healthy food? $1.33 880 calories $2.79 880 calories Stop and Shop Price Check Sept 2010 Drewnowski 2004 Tight budgets limit food choices; cheap calories provide little nutritional value. 25 The cheap foods that make adults fat starve children of absolutely essential nutrients. Children who do not receive protein and other nutrients during early development are damaged for the rest of their lives. Dr. Margaret Chan WHO GROWN UP BRAINS NEED NUTRIENTS TOO brain Help Connect the Dots 29 Energy Insecurity and the Heat or Eat Dilemma Limited or uncertain access to home heating or electricity Moderately energy insecure: received a letter threatening utility shut-off in the last year Severely energy insecure: actual utility shut-off, at least one day with no energy for heating or cooling, or have used a cooking stove as a heating source in the last year Effects of Energy Insecurity Compared with infants and toddlers in households that were energy secure, those in households with just moderate energy insecurity were: • More than twice as likely to live in a food-insecure household • 79% more likely to be child food insecure • 34% more likely to be reported in fair or poor health • 22% more likely to have been hospitalized since birth Housing Insecurity Household is overcrowded, doubled up with another family and/or has moved twice or more in the last year Effects of Housing Insecurity Compared to children in families that are stably housed, children in families who are housing insecure are more likely to be: • Food Insecure • In poor health • At risk for developmental delays Economic Hardship Housing Insecurity Food Insecurity Energy Insecurity Scoring: Cumulative Hardship Index • Score of 0, 1, or 2 for each hardship 0= Secure 1= Moderately insecure 2= Severely insecure • Total possible score of 6 0= No Hardship 1-3= Moderate Hardship 4-6= Severe Hardship Majority of Families Experience Hardship (N=7,141) • 37% (N=2,640) No hardship • 57% (N=4,075) Moderate hardship • 6% (N=426) Severe hardship • Increasing scores on the cumulative hardship index, indicating worsening material conditions What Do We Mean by Child Wellness? • Good or excellent health • No hospitalizations • Not at developmental risk • Not overweight or underweight Results: Bivariate (N=7,141) Hardship and Wellness Outcome No Moderate Severe Hardship Hardship Hardship (N=2640) (N=4075) (N=426) Wellness 46% 42% 35% (N=1209) (N=1712) (N=148) (p<0.0001) Multivariate Logistic Regression I Children with severe vs. no hardship had AOR 0.66 (95% CI 0.52, 0.84, p=.001) of “wellness” after controlling for covariates Multivariate Logistic Regression II Children with severe vs. moderate hardship had AOR 0.74 (95% CI =0.59, 0.93, p=.01) of “wellness” after controlling for covariates Multivariate Logistic Regression III Children with moderate vs. no hardship had AOR 0. 89 (95% CI =0. 80,0.99, p=.01) of “wellness” after controlling for covariates Can We Fix It? Emergency Fixes EMERGENCY FOOD NETWORK Is That All That Can Be Done? Fixing Hunger and Hardship Long-Term is a Political Issue Which Programs Promote Healthy Height and Weight? • • • • WIC CHILDCARE FEEDING LIHEAP HOUSING SUBSIDY Which Programs Decrease Poor Health/Hospitalizations? • • • • WIC SNAP LIHEAP CHILDCARE FEEDING Which Programs Decrease Developmental Risk? • SNAP • WIC • HOUSING SUBSIDIES Riding Two Advocacy Horses 50 PERINATAL EFFECTS I • Fetal Hypoxia • Increased risk spontaneous abortion and still birth PERINATAL EFFECTS II • Low Apgars • Depressed – Birth Weight – Head Circumference – Length • ? Congenital Abnormalities POSTNATAL EFFECTS • • • • Increased risk SIDS Attention Deficits Lower IQ Increased risk exposed child will grow up to be adult addict • Sleep problems Stone et. al. Behav Sleep Med 7:196-207, 2009 Buka et. al. Am J Psychiatry 160:1978-84, 2003 South Carolina Judges Speak • “Now this little baby is born with crack, when he is seven year old, they have an attention span that long. They can’t run. They just run around in class like a little rat. Not just black ones. White ones too.” (State v. Collins Pickens County 1991) • “Sick and tired of these girls having these bastard babies on crack cocaine.” (State v. Crawley 1994) Buying Into Stigma Jeopardizes Mothers and Children atlanta meeting FERGUSON V CITY OF CHARLESTON • Health professionals selectively screened urine of medically indigent obstetric for cocaine • Reported positive results to police • Pregnant and post-partum women (all but one African American) arrested for possession of an illegal drug, delivery of drugs to a minor, or child abuse 63 FERGUSON VS CITY OF CHARLESTON SUPREME COURT RULED POLICY UNCONSTITUTIONAL 6-3 IN MARCH 2001 65 BUT NOW THERE ARE 40 NEW PROSECUTIONS IN ALABAMA ALONE 67 Prevalence of Food Insecurity in the United States, 1999–2008. Seligman HK, Schillinger D. N Engl J Med 2010;363:6-9. Children’s Share of Domestic Federal Spending From 1960 to 2008 children’s share of federal domestic spending declined from 20% to 15% WHY BOTHER? When You Can’t Do Anything Else: Document! 72 Thank You! www.childrenshealthwatch.org 73 88 E. Newton Street | Vose Hall 4th Floor | Boston, MA 02118 | tel: 617.414.6366 | info@childrenshealthwatch.org