Chapter 17 Overview

advertisement

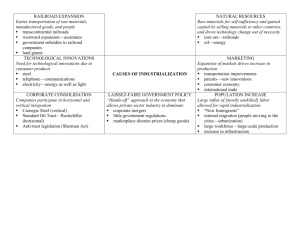

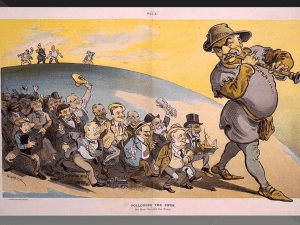

CHAPTER 17 An Industrial Giant CHAPTER OVERVIEW Essentials of Industrial Growth. American manufacturing flourished in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. New natural resources were discovered and exploited, creating opportunities that attracted the brightest and most energetic Americans. The national market grew, protected from foreign competition by tariffs, and foreign capital entered the market freely. European immigrants provided the additional labor needed for industrial expansion. Advances in science and technology created new machines and power sources, which increased productivity. Railroads: The First Big Business. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, railroads were probably the most significant element in American economic development. Important as an industry themselves, railroads also contributed to the growth and development of other industries. Railroads developed into larger and more integrated systems, and their executives, including Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould, became some of the most powerful and wealthiest people in the country. Railroad equipment became standardized, as did time zones. Land grant railroads helped to settle the West by selling their lands cheaply and on easy terms to settlers. New railroad technology, including the air brake and more powerful locomotives, made it possible for larger trains to travel at faster speeds. Iron, Oil, and Electricity. The transformation of iron manufacturing affected the United States almost as much as the development of railroads. New techniques, including the Bessemer process, made possible the mass production of steel. The huge supply of iron ore and coal in the United States allowed for the rapid growth of steel production. The Mesabi Range yielded enormous quantities of easily mined iron. Pittsburgh, surrounded by vast coal deposits, became the iron and steel center of the country. The petroleum industry expanded even more spectacularly than iron and steel. New refining techniques enabled refiners to increase the production of kerosene, which, until the development of the gasoline engine, was the most important petroleum product. Technological advances and the growth of an urban society led to the creation of new industries, such as the telephone and electric light businesses. Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876, and his invention quickly proved its practical value. Of all Edison’s many inventions, the most significant was the incandescent light bulb. The Edison Illuminating Company opened a power station in New York, and power stations began to appear everywhere. The substitution of electricity for steam power in factories had an impact comparable to the substitution of steam for water power before the Civil War. Competition and Monopoly: The Railroads. The growing importance of expensive machinery and economies of scale led to economic concentration. Deflationary pressures after 1873 led to falling prices and increased competition, which cut deeply into railroad profits. Railroads attempted to increase the volume of shipping by giving rebates, drawbacks, and other discounts to selected customers. Sometimes these discounts were far beyond what the economies of bulk shipment justified; in order to make up for these losses, railroads charged higher rates in areas where no competition existed. The combination of lost revenue from rate cutting and inflated debts forced several railroads into receivership in the 1870s. In the 1880s, the major railroads responded to those pressures by creating interregional systems. These became the first giant corporations. Competition and Monopoly: Steel. The iron and steel industry was also intensely competitive; production continued to increase, but demand varied erratically. Andrew Carnegie used his talents as a salesman and administrator, along with his belief in technological improvements, to create the Carnegie Steel Company, which dominated the industry. Alarmed by Carnegie’s control of the industry, makers of finished steel products considered combining their resources and making steel themselves. In response, Carnegie threatened to turn out finished products. J. P. Morgan averted a steel war by buying out Carnegie, his main competitor, and the main fabricators of finished products. The new combination, United States Steel, was the first billion-dollar corporation. Carnegie retired to devote his life to philanthropy. Competition and Monopoly: Oil. Intense competition among refiners led to combination and monopoly in the petroleum industry. John D. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company in 1870. He used technological advances and employed both fair and unfair means to destroy his competition or to persuade them to join forces with him. By 1879, Rockefeller controlled 90 percent of the nation’s oil refining capacity. To maintain his monopoly, Rockefeller developed a new type of business organization, the trust. Competition and Monopoly: Retailing and Utilities. Utilities, such as the telephone and electric lighting industries, also formed monopolies in order to prevent costly duplication of equipment and to protect patents. Bell and Edison fought lengthy and expensive court battles to defend their inventions from imitators and competitors. Competition between General Electric Company and Westinghouse dominated the electric lighting industry. The life insurance business expanded after the Civil War, and it, too, became dominated by a few large companies. In retailing, this period saw the emergence of urban department stores, including Wanamaker’s and Marshall Field. The department stores advertised heavily and stressed low prices, efficient service, and guaranteed products. American Ambivalence to Big Business. The expansion of industry and its concentration in fewer hands changed the way many people felt about the role of government in economic and social affairs. Americans professed to believe that the government should not intervene in the economy, a policy known as laissez-faire. Certain intellectual currents encouraged this approach. By the 1870s, Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species and its theory of natural selection exercised a powerful influence on American public opinion. Some theorists, such as William Graham Sumner of Yale, applied Darwin’s theory to social and economic interactions. Although Americans disliked powerful government and strict regulation of the economy, they did not object to all involvement by the government in the economic sphere. The growth of huge industrial and financial organizations frightened many people. At the same time, people wanted the goods and services that big business produced. The public worried that monopolists would raise prices; still more significant was the fear that monopolies would destroy economic opportunity and threaten democratic institutions. Reformers: George, Bellamy, Lloyd. The popularity of several reformers reflected the growing concern over the unequal distribution of wealth and the power of corporations. In Progress and Poverty (1879), Henry George argued that labor was the only true source of capital. He proposed a “single tax” on wealth produced by appreciation of land values. Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking Backward (1888), described a future in which America was completely socialized and carefully planned. Bellamy’s ideal socialist state arrived without revolution or violence. Henry Demarest Lloyd’s Wealth Against Commonwealth (1894) denounced the Standard Oil Company. His forceful but uncomplicated arguments made Lloyd’s book convincing to thousands. Despite their criticisms, these writers did not question the underlying values of the middle-class majority, and they insisted that reform could be accomplished without serious inconvenience to any individual or class. Reformers: The Marxists. By the 1870s, the ideas of the Marxian socialists began to penetrate the United States. The Marxist Socialist Labor party was founded in 1877. Laurence Gronlund’s The Cooperative Commonwealth (1884) attempted to explain Marxism to Americans. The leading voice of the Socialist Labor party, Daniel De Leon, was a doctrinaire revolutionary who insisted that workers could improve their lot only by adopting socialism and joining the Socialist Labor party. He paid scant attention to the opinions or the practical needs of common working people. The Government Reacts to Big Business: Railroad Regulation. Political reaction to the growth of big business came first at the state level and dealt chiefly with the regulation of railroads. Strict railroad regulation resulted largely from agitation by the National Grange and focused on establishing reasonable maximum rates and outlawing unjust price discrimination. In Munn v. Illinois (1877), the Supreme Court ruled that such regulations by states were constitutional when applied to businesses that served a public interest. However, the Supreme Court declared invalid an Illinois law prohibiting discriminatory rates between long and short hauls in the Wabash case (1886) on the grounds that a state could not regulate interstate commerce. The following year, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act, which required that railroad charges be reasonable and just. It also outlawed rebates, drawbacks, and other competitive practices. In addition, the act created the Interstate Commerce Commission, the first federal regulatory board, to supervise railroad regulation. The Government Reacts to Big Business: The Sherman Antitrust Act. The first antitrust legislation originated in the states. Federal action came with the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890), which declared illegal trusts or other combinations in restraint of trade or commerce. The Interstate Commerce Act sought to outlaw the excesses of competition; the Sherman Act intended to restore competition. The Supreme Court undermined the Sherman Act when it ruled that the American Sugar Refining Company, which controlled 98 percent of sugar refining, was engaged in manufacturing and therefore its dominance did not restrict trade. In later cases, however, the Court ruled that agreements to fix prices did violate the Sherman Act. The Labor Union Movement. At the time of the Civil War, only a small percentage of American workers were organized, and most union members were skilled artisans, not factory workers. The growth of national craft unions quickened after 1865. The National Labor Union was founded in 1866, but its leaders were out of touch with the practical needs and aspirations of workers. They opposed the wage system, strikes, and anything that increased laborers’ sense of membership in the working class. Their major objective was the formation of worker-owned cooperatives. Founded in 1869, the Knights of Labor supported political objectives that had little to do with working conditions and rejected the idea that workers must resign themselves to remaining wage earners. The Knights also rejected the grouping of workers by crafts and accepted blacks, women, and immigrants. Membership in the Knights grew in the 1880s, encouraged by successful strikes against railroads. In 1886, agitation for an eight-hour day gained wide support. Clashes between workers and police in Chicago led to a protest meeting at Haymarket Square. A bomb tossed into the crowd killed seven policemen and injured many others. The American Federation of Labor. The violence in Chicago damaged organized labor, especially the Knights of Labor, which the public associated with anarchy and violence. Membership in the Knights declined. A combination of national craft unions, the American Federation of Labor, replaced the Knights of Labor as the leading labor union. Led by Adolph Strasser and Samuel Gompers, the AFL concentrated on organizing skilled workers. It fought for higher wages and shorter hours. The AFL accepted the fact that most workers would remain wage earners and used its organization to develop a sense of common purpose and pride among its members. The AFL avoided direct involvement in politics and used the strike as its primary tool to improve working conditions. Labor Militancy Rebuffed. Threatened by the growing size and power of their corporate employers, the substitution of machines for human skills, and the influx of foreign workers willing to accept low wages, labor grew increasingly militant. In 1877, a railroad strike shut down two-thirds of the nation’s railroad mileage. Violence broke out, federal troops restored order, and the strike collapsed. In 1892, violence marked the strike against Carnegie’s Homestead Steel plant. The defeat of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers eliminated unionism as an effective force in the steel industry. The most important strike of the period took place in 1894, when Eugene Debs’s American Railway Union struck the Pullman Company. President Cleveland broke the strike when he sent federal troops to ensure the movement of the mail. When Debs defied a federal injunction to end the strike, he was jailed for contempt. Whither America, Whither Democracy? Each year more of America’s wealth and power seemed to fall into fewer hands. Bankers dominated major industries. Centralization increased efficiency but raised questions about the ultimate effects of big business on democracy. The defeat of the Pullman strike demonstrated the power of courts to break strikes. The federal government obtained an injunction in that case by asserting that the American Railway Union was engaged in a combination in restraint of trade prohibited by the Sherman Act. After the failure of the Pullman strike, Debs became a socialist. People, Places, and Things Laissez-faire Social Darwinism The Grange (“Granger laws”) American Federation of Labor (AFL) Interstate Commerce Act (1887) Knights of Labor Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) Collective bargaining Bessemer Process Standard Oil General Electric U.S. Steel Progress and Poverty Wealth Against Commonwealth Pullman strike Jay Gould J. Pierpont Morgan Andrew Carnegie John D. Rockefeller William Graham Sumner Edward Bellamy Terence Powderly Samuel Gompers Munn v. Illinois (1887) Wabash, Sr. Louis & Pacific Railroad v. Illinois (1886) United States v. E.C. Knight (1895)