The Relationship between Quantifiers & Math: A Proposal

advertisement

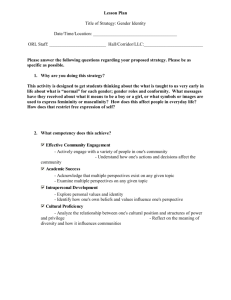

The Relationship between Quantifiers & Math: A Proposal Barbara Zurer Pearson (w/ Tom Roeper) in preparation for a visit to Univ of WalesBangor in Spring ‘09 UMass-Amherst Language Acquisition Colloquium 9/22/08 Evolution of the project: • Submitted NIH R03 in 2005 • Submitted NSF Role (w/ Bev Woolf of CS) • Submitted NIH R21 (exploratory study) 2006 • (some of the NIH critique on Handout p. 2….Guess who was on the panel?!) • Small funding from ESRC in Bangor, Spring 2009 (need to pilot more before then). Hence our meeting today to get started. Organization 1. Some observations of non-adult interpretations of quantifiers (not new) 2. Linguistic (syntactic/ semantic/ pragmatic) aspects of the misinterpretations (not new) 3. Prediction of effect of quantifier understanding on math performance (new) 4. Potential cross-linguistic/ cross dialect effects of quantifier interpretation, with corollary effects on math understanding (new—needs more development) 4b. Potential 2-way relationship Quantifiers <=> Math (also thin) 5. How could one study the hypothesized relationships? Historical Examples • • • • • Piaget (1964) Roeper & Matthei (1974) De Villiers & Roeper (1993) Philip 1995 (classic spreading) Roeper, Pearson & Strauss (2004-6) (add in bunny-spreading) • Negative displacement: (many, Lidz & Musolino 2002?) Piaget: Are all the circles blue? Not this one! ? = Are all the circles all of the blue things? Roeper & Matthei: choose the picture where “some of the boxes are black.” ?= the boxes are some black De Villiers & Roeper (’93): There’s a horse that every boy is on. Bill Philip: (“classic” spreading): Is every girl riding a bike? Copyright The Psychological Corporation 2000 Roeper, Strauss & Pearson: (bunny spreading) Is every dog eating a bone? Copyright The Psychological Corporation 2000 Negative displacement • Every student can’t afford a car. • Adults prefer: = “not every” = “some” Only some students can afford a car • Children prefer: = no students can afford cars, i.e. no students have cars One of Tom’s favorites: Do the boys have two hands or four hands? Collectively or distributively—i.e. with an implicit “each” Our proposal: • These are linguistic (potentially syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic)—but not necessarily mathematical--obstacles. • They may have an impact on children’s understanding of math concepts—and especially their ability to do “word problems.” • Problems even greater for those speaking a non-mainstream dialect –or with a background in a different language. It’s an empirical question, i.e. testable. • Test children’s knowledge of quantifiers • Test children’s knowledge of math (concepts, computation, and word problems) • Include participants from mainstream Am English, Hispanic, and African American English background. • Do think-alouds for the comprehension and production tasks to probe children’s thinking about the meanings of the quantified expressions in the story problems. • Use a regression analysis to see whether quantifier knowledge contributes to word problem success over and above computational skill (and especially for children of different linguistic backgrounds) Testing children’s knowledge of quantifiers • 4 quantifiers: all, every, each, some, most • 3 language groups: MAE, AAE, Hispanic BL • 7 ages (4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, adult) (or 4) • 10 participants per cell • 4 semantic properties – – – – Exhaustivity, Distributivity/ collectivity, concord/ scope, displacement And testing math--Materials/ Tasks • Comprehension w/ abstract stimuli • Comprehension through production (drawing) • Quantifier probes in text context • Math probes (ARPS placement tests; Robbie Case tests of math concepts; Berkeley people??) • Plus DELV-Screener LVS or BESA First steps 1. Find out where this is likely to actually be an issue for children (i.e. examine math materials for potential ambiguities) 2. Establish that children’s quantifier understanding is engaged when they’re doing math (i.e. pilot more kids) 3. Hone the tests for quantifier understanding to make sure we can operationalize it adequately. 4. Find what we hypothesize won’t differ across languages (to motivate the crucial role of language in the quantifier parts). Step 1: Find Quantifier issues in real math tests and classes From www.mcasmentor.com (Sorry, can’t find the picture) • Liu is separating the figures below according to their properties. There are at least three figures in each group. So far, he has made two different groups. List at least 3 figures that could go into each group. Explain what all the figures in each group have in common. • I assume it’s something like this: Potential ambiguities, especially if you’re not sure about the meaning of “each” in: “some figures could go into each group” • Is that 1 group per figure? • Or can one figure go into both groups? • Do all the figures have something in common regardless of group, or only by group? From an elementary math class for adult bilinguals: • Example from Vanessa Hill • Given this problem: • Jalal has ten pockets and forty-four pennies. He wants to put his pennies in his pockets in such a way so each pocket contains a different number of pennies. Can he do it? Explain your answer. • The students (adult bilinguals) did not immediately grasp that “each” directed them to make 1 group per pocket. • Nor did they understand without explicit explanation that they were to use all 44 pennies. From the Amherst Elementary School Math Placement Test: a girl aged 6;9 • “How many sets of 10 and how many ones are in the picture?” •She very carefully counted two sets of 10 to confirm that there were 10 in each of them, and then said “3 tens and 1 ones” —as if the question had an elliptical “sets”: “how many sets of ones were there.” MCAS test asks for “one more number that goes in each of the four spaces in the diagram.” (could be impossible) 5 Multiples of 3 Multiples of 4 24 8 9 1 From 6th grade Math CAS, p. 129 Teenagers/ dialect issues • Eleanor Orr (1987), Twice as less: Black English and the performance of Black children in mathematics and science. • Orr worked with AA teenagers at a private school in DC. They did a lot of talking and writing in working their math problems, and she uncovered lots of conceptual errors. • For example: Twice as less—how much is that?! – How much is twice as less as (100?) – (less than what?) Steps 2 & 3: Examples of our probes (with pre-pilot results)— ABSTRACT STIMULI Distributivity/ Collectivity f. Do the boxes have three triangle tops=> collective (yes) g. Do all the boxes have three triangle tops => collective (yes)/ distrib (no) h. Do most of the boxes have three triangle tops => no i. Does every box have three triangle tops => no Abstract stimuli for concord/ scope Do all the boxes have a circle => yes Do all the boxes have all circles => if yes = concord/ if no, non-concord. To test displacement “Every boy does not have a hat? Is that right? Show me.” Answer Yes i.e. = (not every boy) has a hat—Will point to the boys with no hats Answers No i.e. = every boy (does not have a hat) = every boy has no hat –> point to boys with hats Production Questions: “Draw what the sentences say.” • . Draw a picture with lots of circles – Where all the circles are black. – Where all the circles are all black. – Where the circles are some black. – Where every circle has no black. • Draw a picture with 3 boys: – Where every boy is on a box. – Where there is a box that every boy is on Drawing distributivity (or not) • Draw me some flowers and vases, like this: – The flowers are all in a vase. – All of the flowers are in vases. – Each flower is in a vase. – Each flower is in vases. – The flowers are each in a vase. – Every flower is in every vase. • Word problems on a separate handout. • Examples from “pre-pilot”—kids engaging their quantifier knowledge (whatever it is) in doing math…. Drawing by an 11 year old boy doing our production task For “Every boy is on a box” AND “There is a box that every boy is on.” Cf. de Villiers & Roeper 1993 —6-year-olds get the relative clause barrier. Drawing by boy 6;9 (and similar one by 11-yearold) for “There is a box every boy is on.” An apparent violation of the presupposition for “every” that there needs to be more than one—and maybe more than two—for “every.” Other curious interpretations • As one 6-year-old told us when asked “who was wearing a hat” (from an array with several boys wearing hats and others without), “I don’t know which one to tell you” (But, on the way back to the classroom, he told me about his baseball team (“Who is on your team?”)—exhaustively. Is it a pragmatic issue?) 11-year-old boy: “Do all the boxes have every circle?” No, (he wanted all the boxes completely filled with circles—he colored the boxes in with tons of circles.) Same interpretation for “Does each box have each circle?” AND “Does every box have every circle?” Letting aside what his interpretation was, all of the quantifiers had the same properties. Control sentence: “Do boxes have circles inside?” Several children said “no” (requiring exhaustivity where it’s not warranted) Math to Quantifiers • How much does one have to know about comparing inequalities to interpret “most”? (Had a 4-year-old who couldn’t do one-to-one counting very well and couldn’t compare near quantities. Couldn’t do “most” at all.) • One-to-one counting allows what?? ) have some speculation in NSF??! (note to self: do we Cross-dialect dimensions: AAE • AAE & bunny spreading: AAE kids didn’t use more Classic spreading, but more children did BOTH CS and BS) • Multiple negation—may predispose to spreading Cross-linguistic dimensions: Spanish-influenced English • Multiple negation • (Ana P’s) interpretation of generics (the lion over there vs “the lion” as a species) • Much/ many (no grammatical count-non-count distinction). See Gathercole, 2002 • Each/every (no word for every) – Use each and all • What will Spanish children prefer in distinctions between collective and distributive readings? Welsh predisposition to collective over individual reading • What's in a noun? Welsh-, English-, and Spanishspeaking children see it differently Mueller Gathercole et al. First Language.2000; 20: 055-90 Welsh children, whose language is not as clearly marked for singular and plural—and there are many plurals which are unmarked and they take a suffix for the singular--Children were more likely to interpret a novel noun as a collection than were English children. (As background, they list some experiments with English children, in support of innate biases, that collection nouns (“forest”) are less likely guesses for English children till older. Not so in Welsh.) We’re going to look at some strange things that I have— that I bet you’ve never seen. The bear always wants just what I have. • . A B Which of these is the bear’s blicket? Welsh children chose group significantly more often than English or Spanish children. • . Other choices didn’t show cross-linguistic differences. (Did another more complicated experiment to make sure they weren’t just “matching.” Previous studies • Not on the radar for math teachers, even those who write about math and language • Jose Mestre in late 80s early 90s. Studied how college students translated word problems into equations (like Orr). • Orr Twice as Less (examples in NSF??) • Helen Stickney on “most” (like “mostly”) Consensus • There’s much too much for one study, even one set of studies (and Tom gets even more ideas to broaden it whenever we talk about it (like today). • Should work more on the actual math problems to find the nature of the ambiguities. (Get Peggy to look at them with me??) Next studies for us?? • Need to narrow question to something do-able for this year, including the time in Wales. • I would be happy to have an age-stratified sample do a set of drawings of the expressions—for collective/ distributive (like the flowers in vases). • Also want to make a methodology for using a tablet PC for stimuli and recording responses and even a light pad for the children’s drawings.