TED STOLZE * PHILOSOPHY 100

advertisement

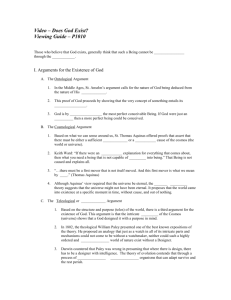

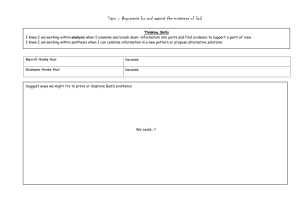

TED STOLZE – PHILOSOPHY 100 NOTES ON GARY COX, THE GOD CONFUSION Topics in Cox’s Book • The Idea of God • Sources of the Idea of God • Arguments for the Existence of God • God and the Problem of Evil The Idea of God Three Key Divine Attributes are: • Omnipotence (All-powerful) • Omniscience (All-knowing) • Omnibenevolence (All-good) Possible Sources of the Idea of God • From God (Descartes) • Hallucination (Dawkins?) • What Science Can’t Explain/“God of the Gaps” (Dawkins?) • From Parents/“Daddy” (Freud) • Social Cohesion (Durkheim) • (Contradictory) Ideology (Marx) Arguments for the Existence of God 5 • Ontological • Cosmological o Unmoved Mover o First Cause o Necessary Cause • Teleological • From Degree • Moral A Version of the Ontological Argument 1. Define “God” as a being greater than which none can be thought. 2. Assume that God exists only in the imagination. 3. But it is greater for something to exist not only in the imagination but also in reality. 4. Therefore, God is not a being greater than which none can be thought. 5. But this contradicts #1. 6. Therefore, God exists not only in the imagination but also in reality. Two Objections to the Ontological Argument • The Perfect Island (Gaunilo) • Existence is not a Predicate (Kant) A Version of the Cosmological Argument 1. If the universe began to exist, then the universe has a cause. 2.The universe began to exist. 3.Therefore, the universe has a cause. • • • Watch a brief video overview: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6CulBuMCLg0&sns=em Also watch Prof. William Lane Craig debate Richard Dawkins (in an empty chair) regarding the Cosmological Argument: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TUIFjxYKEAU&list=PL3gdeV4Rk9Ef6jhlYLPp1UwzvnL_kbqw Objections to the Cosmological Argument • Does the universe have a beginning? • Why think that the First Cause is a personal God? • Does the universe have only one Cause? • Why worship the First Cause? John Wisdom’s Parable of the Garden 10 "Two people return to their long neglected garden and find among the weeds a few of the old plants surprisingly vigorous. One says to the other, “It must be that a gardener has been coming and doing something about these plants.” Upon inquiry they find that no neighbor has ever seen anyone at work in their garden. The first man says to the other, “He must have worked while people slept.” The other says, “No, someone would have heard him and besides, anybody who cared about the plants would have kept down these weeds.” The first man says, “Look at the way these are arranged. There is purpose and a feeling for beauty here. I believe that someone comes, someone invisible to mortal eyes. I believe that the more carefully we look the more we shall find confirmation of this.” They examine the garden ever so carefully and sometimes they come on new things suggesting that a gardener comes and sometimes they come on new things suggesting the contrary and even that a malicious person has been at work. Besides examining the garden carefully, they also study what happens to gardens left without attention. Each learns all the other learns about this and about the garden. Consequently, when after all this, one says, “I still believe a gardener comes,” while the other says, “I don’t,” their different words now reflect no difference as to what they have found in the garden, no difference as to what they would find in the garden if they looked further and no difference about how fast untended gardens fall into disorder.... What is the difference between them?"(From John Wisdom, “Gods,” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 45 [1944-1945]: 185-206, 191-192) William Paley (1743-1805) William Paley’s Watch Analogy “In crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone and were asked how the stone came to be there, I might possibly answer that for anything I knew to the contrary it had lain there forever; nor would it, perhaps, be very easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place, I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that for anything I knew the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer serve for the watch as well as for the stone? Why is it not as admissible in the second case as in the first? For this reason, and for no other, namely, that when we come to inspect the watch, we perceive—what we could not discover in the stone—that its several parts are framed and put together for a purpose, e.g., that they are so formed and adjusted as to produce motion, and that motion so regulated as to point out the hour of the day; that if the different parts had been differently shaped from what they are, of a different size from what they are, or placed after any other manner or in any other order than that in which they are placed, either no motion at all would have been carried on in the machine, or none which would have answered the use that is now served by it. To reckon up a few of the plainest of these parts and of their offices, all tending to one result; we see a cylindrical box containing a coiled elastic spring, which, by its endeavor to relax itself, turns round the box. We next observe a flexible chain— artificially wrought for the sake of flexure—communicating the action of the spring from the box to the fusee. We then find a series of wheels, the teeth of which catch in and apply to each other, conducting the motion from the fusee to the balance and from the balance to the pointer, and at the same time, by the size and shape of those wheels, so regulating that motion as to terminate in causing an index, by an equable and measured progression, to pass over a given space in a given time. We take notice that the wheels are made of brass, in order to keep them from rust; the springs of steel, no other metal being so elastic; that over the face of the watch there is placed a glass, a material employed in no other part of the work, but in the room of which, if there had been any other than a transparent substance, the hour could not be seen without opening the case. This mechanism being observed—it requires indeed an examination of the instrument, and perhaps some previous knowledge of the subject, to perceive and understand it; but being once, as we have said, observed and understood—the inference we think is inevitable, that the watch must have had a maker—that there must have existed, at some time and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer, who comprehended its construction and designed its use.” (From Natural Theology [1800], chapter 1) A Version of the Teleological Argument 13 1. We conclude that watches were made by intelligent designers because they have parts that work together to serve a purpose. 2. We have the same evidence that the universe, and some of the natural objects in it, were made by an intelligent designer: they are also composed of parts that work together to serve a purpose. 3. Therefore, we are entitled to conclude that the universe was made by an intelligent designer. Objections to the Teleological Argument • • • • Could there be multiple designers (a polytheistic objection)? How orderly, harmonious, and beautiful is the universe really? (a Humean objection) Why think that a designer would be all-good? (another Humean objection) There is an alternative explanation for the emergence of natural order and complexity. (a Darwinian objection) Darwin on Paley and Intelligent Design “Although I did not think much about the existence of a personal God until a considerably later period of my life, I will here give the vague conclusions to which I have been driven. The old argument of design in nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered. We can no longer argue that, for instance, the beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door by man. There seems to be no more design in the variability of organic beings and in the action of natural selection, than in the course the wind blows. Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.” (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, edited by Nora Barlow [NY: Norton, 2005 (1958)], p. 73.) Darwin’s Argument for Natural Selection 1. There is a geometrical increase in organisms. 2. The “struggle for existence” over survival leads to the emergence of variations in characteristics of members of a species. 3. There exists a heritability of characteristics. 4. Characteristics with “survival value” will be passed on to future generations. 5. Therefore, there exists a variation among and modification of species. A Darwinian Argument 1. 2. 3. The wonders of nature occurred (a) by chance, (b) as the product of intelligent design, or (c) as the result of evolution by natural selection. Evolution by natural selection explains the existence of these things much better than either chance or intelligent design does. Therefore, the wonders of nature are best explained as the products of evolution by natural selection. An Evolutionary Theist Counter-Argument 1. Everything that exists within the universe—including evolution by natural selection—is part of a vast system of causes and effects. 2. But the universe itself requires an explanation—why does it exist? 3. The only plausible explanation is that God created it. 4. Therefore, to explain the existence of the universe, it is reasonable to believe in God. 5. Therefore, to explain the existence of evolution by natural selection, it is also reasonable to believe in God. Darwin’s Conclusion to On the Origin of Species “It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction; Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of lessimproved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed [by the Creator*] into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” (From Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species [1859], pp. 489-90) *A phrase Darwin added to the 2nd edition (1860) and maintained through the 6th edition (1876). The Argument from Degree 1. Things in the world possess different degrees of perfection. 2. If there are things that possess degrees of perfection, then there must exist that which causes these perfections and most fully possesses these perfections. 3. Therefore, there must exist that which causes these perfections and most fully possesses these perfections--that which is most fully perfect, namely, “God.” Objections to the Argument from Degree Why not many maximally perfect things? Many kinds of things cannot even be perfect (for example, a meal or a moment). A greater perfection can be a cause of lesser perfections without being an absolute or complete perfection. Why think that the greatest perfection is a personal God? Why think that an actual X must be caused by that which is already actual X? (For example, fire is not always caused by something hot—sodium and water at room temperature.) The Moral Argument 1. There is no guarantee of justice in this world. 2. The virtuous are not necessarily rewarded with the happiness that ought to complement their virtue. 3. But without some such future reward, there would be no motivation to act justly—the result would be a condition of moral futility. 4. Therefore, there must be a God-given guarantee of justice in the next world. Objections to the Moral Argument But why would only a personal single God bring about such a reward for virtue? (Why couldn’t it result from many deities or a nonpersonal cosmic moral law like karma?) Perhaps virtue has simply evolved. Perhaps virtue is its own reward. Perhaps moral futility is correct. Theodicy vs. Defense A “theodicy” provides a complete justification of God’s actions regarding evil, whereas a “defense” only sketches out a possible explanation. Genuine Evil There are at least some examples of what we could call “genuine evil.” In other words, these instances of evil are not illusory or simply mischaracterized as bad but are in fact cases of objective pain, suffering, or some other harm. Natural vs. Human-Caused Evil However, this distinction breaks down when we consider such apparently “natural” evils that (indirectly) result from human activities, for example: • birth defects due to toxic exposure in the workplace or community • chronic conditions like asthma that result from air pollution • deaths that result from extreme weather patterns (hurricanes, floods, and droughts) caused by global warming Two Levels of Evil (*) • Individual (e.g., limited or selective altruism, contempt or hatred for others deemed “inferior”: psychopathy, racial prejudice, sexism, classism, ageism, homophobia, speciesism…) • Structural (e.g., institutionalized group advantage/disadvantage: racist, heterosexist oppression, poverty, class exploitation, “world alienation” [Hannah Arendt]) NOTE: Structural evil may result from unintended or even well-intended actions by individuals, what Jean-Paul Sartre called “counter-finalities,” e.g. climate change (*) Not covered by Cox Evil as a Problem for Monotheism 1. God is an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good being. 2. If God is all-powerful, then God could create a world without genuine evil. 3. If God is all-knowing, then God knows that there is genuine evil in the world. 4. If God is all-good, then God would want there to be a world without genuine evil. 5. But there is genuine evil in the world. 6. So, God (at least as defined above) does not exist. Sally Haslanger on the Problem of Evil https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9pRzyioUKp0 Two Defenses of God’s Actions Free Will Soul Making The Hiddenness of God Objection (*) We live in a world in which people persist in disbelieving God or having cruel views of God. 2. God does not appear to correct these states. 3. An all-good God would never allow a creature to seek God without finding God in an evident fashion. 4. Therefore, God does not exist. 1. NOTE: Consider the plot of the 1950 movie, The Next Voice You Hear: www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRxf9qS5PUk (*) Not covered by Cox Darwin on the Problem of Natural Evil “That there is much suffering in the world no one disputes. Some have attempted to explain this in reference to man by imagining that it serves for his moral improvement. But the number of men in the world is as nothing compared with that of all other sentient beings, and these often suffer greatly without any moral improvement. A being so powerful and so full of knowledge as a God who could create the universe, is to our finite minds omnipotent and omniscient, and it revolts our understanding to suppose that his benevolence is not unbounded, for what advantage can there be in the suffering of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time? This very old argument from the existence of suffering against the existence of an intelligent first cause seems to me a strong one; whereas, as just remarked, the presence of much suffering agrees well with the view that all organic beings have been developed through variation and natural selection.” (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, edited by Nora Barlow [NY: Norton, 2005 (1958)], p. 75.)