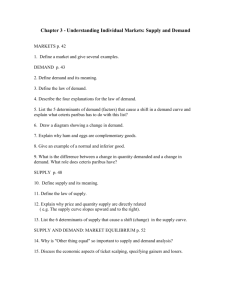

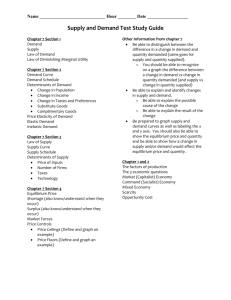

Chapter 2: The Key Principles of Economics

advertisement

What Is Economics? • Economics is the study of the choices made by people who are faced with scarcity. • Scarcity is a situation in which resources are limited and can be used in different ways, so one good or service must be sacrificed for another. 1 of 15 Positive versus Normative Analysis • Positive economics predicts the consequences of alternative actions, answering the questions, “What is?” or “What will be?” 2 of 15 Positive versus Normative Analysis • Normative economics answers the question, What ought to be? Normative questions lie at the heart of policy debates. 3 of 15 The Economic Way of Thinking • The economic way of thinking is best summarized by British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) as follows: “The theory of economics does not furnish a body of settled conclusions immediately applicable to policy. It is a method rather than a doctrine, an apparatus of the mind, a technique of thinking which helps its possesor draw correct conclusions.” 4 of 15 The Economic Way of Thinking • Three elements of the economic way of thinking: 1. Use assumptions to simplify • Eliminate irrelevant details and focus on what really matters. Keep in mind that simplifying assumptions do not have to be realistic. 5 of 15 The Economic Way of Thinking • Three elements of the economic way of thinking: 2. Isolate variables—Ceteris Paribus • Economists are interested in exploring relationships between two variables. A variable is a measure of something that can take on different values. • The expression ceteris paribus means that the effect of other tendencies is neglected for a time. 6 of 15 The Economic Way of Thinking • Three elements of the economic way of thinking: 3. Think at the margin • A small, one-unit change in value is called a marginal change. • Economists use the answer to a marginal question as the first step in deciding whether to do more or less of something. 7 of 15 The Economic Way of Thinking • A key assumption of most economic analysis is that people act rationally, meaning that they act in their own self-interest. • Rational people respond to incentives. 8 of 15 The Principle of Opportunity Cost PRINCIPLE of Opportunity Cost The opportunity cost of something is what you sacrifice to get it. • Most decisions involve several alternatives. The principle of opportunity cost incorporates the notion of scarcity. • There is no such thing as a free lunch. 9 of 15 Opportunity Cost and the Production Possibilities Curve • The production possibilities curve illustrates the principle of opportunity cost for an entire economy. • The ability of an economy to produce goods and services is determined by its factors of production, including labor, land, and capital. 10 of 15 Opportunity Cost and the Production Possibilities Curve • The shaded area shows all the possible combinations of the two goods that can be produced. • Only points on the curve show the combinations that fully employ the economy’s resources. 11 of 15 Opportunity Cost and the Production Possibilities Curve • As we move downward along the curve, we must sacrifice more manufactured goods to get the same 10-ton increase in agricultural goods. • The curve is bowed outwards because resources are not perfectly adaptable for the production of both goods. 12 of 15 Opportunity Cost and the Production Possibilities Curve • An increase in the amount of resources available, or a technological innovation, causes the production possibilities to shift outward, allowing us to produce more output with a given quantity of resources. 13 of 15 Using the Principle: The Cost of College Total opportunity cost of college Opportunity cost of money spent on tuition and books Opportunity cost of college time (4 years at $20,000 per year) Economic cost or total opportunity cost $ 40,000 80,000 $120,000 14 of 15 The Marginal Principle Marginal PRINCIPLE Increase the level of an activity if its marginal benefit exceeds its marginal cost; reduce the level of an activity if its marginal cost exceeds its marginal benefit. If possible, pick the level at which the activity’s marginal benefit equals its marginal cost. 15 of 15 The Marginal Principle • When we say marginal, we’re looking at the effect of only a small, incremental change. • The marginal benefit of some activity is the extra benefit resulting from a small increase in the activity. • The marginal cost is the additional cost resulting from a small increase in the activity. • Thinking at the margin enables us to finetune our decisions. 16 of 15 Example: How Many Movie Sequels? • The marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost for the first two movies, so it is sensible to produce two, but not three movies. Number of Movies Marginal Benefit Marginal Cost 1 $300 million $125 million 2 $210 million $150 million 3 $135 million $175 million 17 of 15 The Principle of Voluntary Exchange PRINCIPLE of Voluntary Exchange A voluntary exchange between two people makes both people better off. • A market is an arrangement that allows people to exchange things. • If participation in a market is voluntary, both the buyer and the seller must be better off as a result of a transaction. 18 of 15 The Principle of Diminishing Returns PRINCIPLE of Diminishing Returns Suppose output is produced with two or more inputs and we increase one input while holding the other input or inputs fixed. Beyond some point—called the point of diminishing returns—output will increase at a decreasing rate. 19 of 15 Comparative Advantage and Exchange Specialization and the Gains From Trade: • We can use the principle of opportunity cost to explain the benefits from specialization and trade. PRINCIPLE of Opportunity Cost The opportunity cost of something is what you sacrifice to get it. 20 of 15 Specialization and the Gains from Trade Table 3.1: Productivity and Opportunity Cost Abe Output per day Opportunity cost Bea Paintings Pizzas Paintings Pizzas 2 6 1 1 3 pizzas 1/3 painting 1 pizza 1 painting • People can benefit by specialization and trade based on opportunity cost. • We say that a person has a comparative advantage in producing a particular product if he or she has a lower opportunity cost than another person. 21 of 15 Specialization and the Gains from Trade Table 3.2: Specialization, Exchange, and Gains from Trade Abe Bea Total Paintings per week Pizzas per week Paintings per week Pizzas per week Paintings per week Pizzas per week Abe and Be are self-sufficient 4 24 1 5 5 29 Abe and Bea specialize 0 36 6 0 6 36 After specializing, Abe and Bea exchange 2 pizzas per painting 0+5=5 (Abe gets 5 painting) 36 – 10 =26 (Abe gives up 10 pizzas) 6–5=1 (Bea gives up 5 paintings) 0 + 10 = 10 (Bea gets 10 pizzas) Gains from specialization and exchange 1 2 0 5 1 7 22 of 15 Production and Consumption Possibilities • Abe starts at the self-sufficient point a1. Specialization moves him to point a2, and exchange moves him down the consumption possibilities curve to point a3. • Bea starts at the self-sufficient point b1. Specialization moves her to point b2, and exchange moves her up the consumption possibilities curve to point b3. • The consumption possibilities curve shows the possible combinations of the two goods when Abe and Bea specialize and exchange two pizzas per painting. 23 of 15 Specialization and the Gains from Trade • Specialization and exchange makes both people better off, illustrating one of the key principles of economics: PRINCIPLE of Voluntary Exchange A voluntary exchange between two people makes both people better off. 24 of 15 Comparative Advantage versus Absolute Advantage • In the previous example, Abe is more productive than Bea in producing both goods. Economists say that Abe has an absolute advantage in producing both goods. • Despite his absolute advantage, Abe gains from specialization and trade because he has a comparative advantage in producing pizza. 25 of 15 The Division of Labor and Exchange • Three reasons for productivity to increase with specialization: 1. Repetition 2. Continuity 3. Innovation • Specialization and exchange result from differences in productivity, which in turn come from differences in innate skills and the benefits associated with the division of labor. 26 of 15 Comparative Advantage and International Trade • Many people are skeptical about the idea that international trade can make everyone better off. Most economists, however, favor international trade. In the words of economist Todd Buchholz: “Money may not make the world go round, but money certainly goes around the world. To stop it prevents goods from traveling from where they are produced most inexpensively to where they are desired most deeply.” 27 of 15 Perfectly Competitive Market • We use the model of supply and demand— the most important tool of economic analysis—to see how markets work. • The model of supply and demand explains how a perfectly competitive market operates. • A perfectly competitive market is a market has a very large number of firms, each of which produces the same standardized product in amounts so small that no individual firm can affect the market price. 28 of 15 The Demand Curve • Here is a list of variables that affect the individual consumer’s decision, using the pizza market as an example: • The price of the product, for example, the price of pizza • The consumer’s income • The price of substitute goods such as tacos or sandwiches 29 of 15 The Demand Curve • Here is a list of variables that affect the individual consumer’s decision, using the pizza market as an example: • The price of complementary goods such as beer or lemonade • The consumer’s tastes and advertising that may influence tastes • The consumer’s expectations about future prices 30 of 15 The Individual Demand Curve and the Law of Demand Table 4.1 Al’s Demand Schedule for Pizza Price Quantity of pizzas per month $2 13 4 10 6 7 8 4 10 1 • The demand schedule is a table that shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded by an individual consumer, ceteris paribus (everything else held fixed). 31 of 15 The Individual Demand Curve and the Law of Demand • The individual demand curve is a graphical representation of the demand schedule. • LAW OF DEMAND: The higher the price, the smaller the quantity demanded, ceteris paribus (everything else held fixed). 32 of 15 The Individual Demand Curve and the Law of Demand • Quantity demanded is the amount of a good an individual consumer or consumers as a group are willing to buy. • A change in quantity demanded is a change in the amount of a good • In this case, an increase in demanded resulting from a price causes a decrease in change in the price of the quantity demanded, and a good. movement upward along the individual’s demand curve. 33 of 15 The Substitution Effect • The substitution effect is the change in consumption resulting from a change in the price of one good relative to the price of other goods. • The lower the price of a good, the smaller the sacrifice associated with the consumption of that good. 34 of 15 The Income Effect • The income effect describes the change in consumption resulting from an increase in the consumer’s real income, or the income in terms of the goods the money can buy. • Real income is the consumer’s income measured in terms of the goods it can buy. 35 of 15 From Individual to Market Demand • The market demand curve shows the relationship between price and quantity demanded by all consumers together, ceteris paribus (everything else held fixed). 36 of 15 The Supply Curve • Here are the variables that affect the decisions of sellers, using the market for pizza as an example: • The price of the product—in this case, the price of pizza. • The cost of the inputs used to produce the product, for example, wages paid to workers, the cost of dough and cheese, and the cost of the pizza oven. • The state of production technology, such as the knowledge used in making pizza. 37 of 15 The Supply Curve • Here are the variables that affect the decisions of sellers, using the market for pizza as an example: • The number of producers—in this case, the number of pizzerias. • Producer expectations about the future price of pizza. • Taxes paid to the government or subsidies received from the government. 38 of 15 The Individual Supply Curve and the Law of Supply Table 4.2 Nora’s Schedule for Pizza Price Quantity of pizzas per month $4 100 6 200 8 300 10 400 12 500 • A firm’s supply schedule is a table that shows the relationship between price and quantity supplied, ceteris paribus (everything else held fixed). 39 of 15 The Individual Supply Curve and the Law of Supply • The individual supply curve is a graphical representation of the supply schedule. Its positive slope reflects the law of supply. • LAW OF SUPPLY: The higher the price, the larger the quantity supplied, ceteris paribus. 40 of 15 The Individual Supply Curve and the Law of Supply • Quantity supplied is the amount of a good an individual firm or firms as a group are willing to sell. • A change in quantity supplied is a change in the amount of a good supplied resulting from a change in • In this case, an increase in the price of the good; price causes an increase in represented graphically by quantity supplied and a a movement along the movement upward along supply curve. the supply curve. 41 of 15 Why is the Individual Supply Curve Positively Sloped? • To determine how much to produce, the individual firm chooses the quantity of output that satisfies the marginal principle. Marginal PRINCIPLE Increase the level of an activity if its marginal benefit exceeds its marginal cost; reduce the level of an activity if its marginal cost exceeds its marginal benefit. If possible, pick the level at which the activity’s marginal benefit equals its marginal cost. 42 of 15 The Marginal Principle and the Output Decision • The marginal benefit of selling a pizza is the price received when the pizza is sold. • Marginal cost is the cost of producing an additional pizza. • The marginal cost of producing the first 299 pizzas is less than the $8 marginal benefit. The marginal principle is satisfied when 300 pizzas are produced. 43 of 15 The Marginal Principle and the Output Decision • An increase in the price shifts the marginal benefit curve upward and increases the quantity at which the marginal principle is satisfied. 44 of 15 From Individual Supply to Market Supply • The market supply curve shows the relationship between price and quantity supplied by all producers together, ceteris paribus (everything else held fixed). • If there are 100 identical pizzerias, market supply equals 100 times the quantity supplied by a single firm at each price level. 45 of 15 Market Equilibrium • Market equilibrium is a situation in which the quantity of a product demanded equals the quantity supplied, so there is no pressure to change the price. 46 of 15 Excess Demand Causes the Price to Increase • Excess demand is a situation in which, at the prevailing price, consumers are willing to buy more than producers are willing to sell. • The market moves upward along the demand curve, decreasing quantity demanded, and upward along the supply curve, increasing quantity supplied. 47 of 15 Excess Supply Causes the Price to Drop • Excess supply is a situation in which, at the prevailing price, producers are willing to sell more than consumers are willing to buy. • The market moves downward along the demand curve, increasing quantity demanded, and downward along the supply curve, decreasing quantity supplied. 48 of 15 Market Effects of Changes in Demand Change in Quantity Demanded versus Change in Demand • A change in price causes a change in quantity demanded. • A change in demand (caused by changes in something other than the price of the good) shifts the entire demand curve. 49 of 15 Increases in Demand • An increase in demand shifts the market demand curve to the right. • At the initial price of $8, there is now excess quantity demanded. • Equilibrium is restored at point n, with a higher equilibrium price and a larger equilibrium quantity. 50 of 15 Causes of an Increase in Demand • An increase in demand can occur for several reasons: • An increase in income (for a normal good). A normal good is a good that consumers buy more of when their income increases. Most goods fall in this category. • A decrease in income (for an inferior good). An inferior good is the opposite of a normal good. Consumers buy more of inferior goods when their income decreases. 51 of 15 Causes of an Increase in Demand • An increase in demand can occur for several reasons: • An increase in the price of a substitute good. When to goods are substitutes, an increase in the price of one good increases the demand for the other good. • A decrease in the price of a complementary good. Two goods are complements when an increase in the price of one good decreases the demand for the other good. 52 of 15 Causes of an Increase in Demand • An increase in demand can occur for several reasons: • An increase in population • A shift in consumer tastes • Favorable advertising • Expectations of higher future prices 53 of 15 Decreases in Demand • A decrease in demand shifts the demand curve to the left. • At the initial price of $8, there is now an excess supply. • Equilibrium is restored at point n, with a lower equilibrium price ($6) and a smaller equilibrium quantity (20,000 pizzas). 54 of 15 Decreases in Demand • A decrease in demand can occur for several reasons: • A decrease in income (for a normal good) • A decrease in the price of a substitute good • A decrease in population • A shift in consumer tastes • Favorable advertising • Expectations of lower future • An increase in the price prices of a complementary good 55 of 15 Market Effects of Changes in Demand Table 4.3 Changes in Demand Shift the Demand Curve (pg. 1) An increase in demand shifts the demand curve to the right when: A decrease in demand shifts the demand curve to the left when: The good is normal and income increases The good is normal and income decreases The good is inferior and income decreases The good is inferior and income increases The price of a substitute good increases The price of a substitute good decreases The price of a complementary good decreases The price of a complementary good increases 56 of 15 Market Effects of Changes in Demand Table 4.3 Changes in Demand Shift the Demand Curve (pg. 2) An increase in demand shifts the demand curve to the right when: A decrease in demand shifts the demand curve to the left when: Population increases Population decreases Consumer tastes shift in favor of the product Consumer tastes shift away from the product Consumers expect a higher price in the future Consumers expect a lower price in the future 57 of 15 Market Effects of Changes in Supply Change in Quantity Supplied versus Change in Supply • A change in price causes a change in quantity supplied. • A change in supply (caused by changes in something other than the price of the good) shifts the entire supply curve. 58 of 15 Increases in Supply • An increase in supply shifts the market supply curve to the right. • At the initial price of $8, there is now excess supply. • Equilibrium is restored at point n, with a lower equilibrium price and a larger equilibrium quantity. 59 of 15 Causes of an Increase in Supply • An increase in supply can occur for several reasons: • A decrease in input costs. • An increase in the number of producers. • Expectations of lower future prices. • Product is subsidized. 60 of 15 Decreases in Supply • A decrease in supply shifts the supply curve to the left. • At the initial price of $8, there is now an excess demand. • Equilibrium is restored at point n, with a higher equilibrium price ($10) and a smaller equilibrium quantity (23,000 pizzas). 61 of 15 Causes of a Decrease in Supply • A decrease in supply can occur for several reasons: • An increase in input costs. • A decrease in the number of producers. • Expectations of higher future prices. • Taxes. If a tax per unit is imposed, which will make the product less profitable, firms will produce less. 62 of 15 Market Effects of Changes in Supply Table 4.4 Changes in Supply Shift the Supply Curve An increase in supply shifts the supply curve to the right when: A decrease in supply shifts the supply curve to the left when: The cost of an input decreases The cost of an input increases A technological advance decreases production cost The number of firms increases The number of firms decreases Producers expect a lower price in the future Producers expect a higher price in the future Product is subsidized Product is taxed 63 of 15 Market Effects of Simultaneous Changes in Supply and Demand • Both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity will increase. • The equilibrium price will decrease and the equilibrium quantity will increase. 64 of 15 Using the Model to Predict Changes in Price and Quantity Predicting the Effects of Changes in Demand • An increase in university enrollment will • A report of pesticide residue on apples increase the demand for apartments, decreases the demand for apples, shifting shifting the demand curve to the right. the demand curve to the left. Both the Both the equilibrium price and the equilibrium price and the equilibrium equilibrium quantity will increase. quantity will decrease. 65 of 15 Using the Model to Predict Changes in Price and Quantity Predicting the Effects of Changes in Supply • Technological innovation decreases • Bad weather decreases the supply of production costs, shifting the supply coffee beans, shifting the supply curve to curve to the right. The equilibrium price the left. The equilibrium price increases, decreases, and the equilibrium quantity and the equilibrium quantity decreases. increases. 66 of 15 Explaining Changes in Price or Quantity • At the same time the quantity • At the same time the price decreased, the increased, the price decreased. quantity decreased. Therefore, the Therefore, the increase in consumption decrease in price was caused by a resulted from an increase in supply, not decrease in demand, not an increase in an increase in demand. supply. 67 of 15