JFK and the Berlin Wall

advertisement

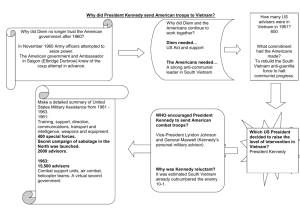

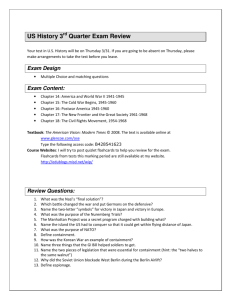

Green Berets Origins The beginnings of the Army Special Forces can be traced all the way back to a small contingent of Confederate Civil War soldiers led by Col. John Mosby. The soldiers staged raids in a manner that more resembles the modern Army Rangers. But it was a another military tactic -- winning the support of the local populations -- that has become a hallmark of the Green Berets. The Special Forces were further defined by the Office of Special Services (OSS), the secretive agency that was created in World War II. During World War II, the OSS was charged with penetrating enemy lines held by the Axis armies. Once inside, the OSS officers helped train and support local resistance movements. In Burma, for example, three OSS officers organized a coalition of native tribesmen into an 11,000-strong guerrilla army -soldiers who band together to engage in irregular warfare tactics -- that killed 10,000 occupying Japanese troops, but lost only 206 of its own fighters [source:SOC]. After World War II, the OSS was disbanded. But the need for the information and organization that the group provided continued. In 1952, three Army officers, led by Brigadier General Robert McClure, were granted permission to create a group of Army soldiers that could carry out sensitive missions on behalf of the United States government. A total of 2,300 openings were created to found the group, although it officially began with just 10 soldiers, including the leadership [source: SpecialOperations.com]. The official Special Forces' base of operations was established at Ft. Bragg, N.C., and soon the ranks grew. Eventually, detachments -- or units -- of as little as 12 men were formed, and bases of operations were set up in the United Sates and throughout the world. In 1953, the first deployment of Green Berets took place. Half of the force was sent to Bad Tolz, West Germany, which served as that group's base of operations. Since that first deployment, the Green Berets have carried out thousands of missions, most in secrecy. Which means that the success of the Green Berets can hardly be measured; after all, how can you quantify something that doesn't happen, like a thwarted war? (CBS News) FORT BRAGG, N.C. -- There is no more famous or poignant image in American history than John F. Kennedy, Jr. on his third birthday saluting his father as JFK was about to be laid to rest. But there was another salute to the slain president that day from men in uniform who considered Kennedy their Godfather. President John F. Kennedy visited Fort Bragg, N.C., in 1961. CBS News All the armed services took part in the funeral procession, but none felt a greater loyalty to their fallen commander-in-chief than the Army's Green Berets. Just two years before, the young president had endorsed the beret and the Special Forces who wore it. Tom Gaffney was there that day in 1961 when JFK visited Fort Bragg, N.C. “That's why Special Forces people have such a strong admiration for President Kennedy,” said Gaffney. Gaffney was a sergeant in the Army Special Forces and part of the demonstration the president had come to see -- everything from the far-fetched down to the nitty-gritty. Tom Gaffney CBS News “My A-team was given the mission of putting on a mock ambush for him,” said Gaffney. Gaffney had already been on a secret mission in Laos, training local tribesmen to fight as anticommunist guerrillas -- unconventional warfare which merited unconventional head gear. “We would love to have something to identify us as being different from the rest of the Army,” said Gaffney. The Army disapproved of the beret as too European looking, not masculine enough. But after Brigadier General William Yarborough told the president Special Forces wanted them, JFK issued a statement that "the green beret will be a mark if distinction in the trying times ahead." Green berets stayed with the casket all the way to the grave and remained on guard until after the Kennedy family had left. CBS News And by the time of his death, Special Forces had doubled in size. “When he recognized Special Forces, he recognized that we needed them, and the Army said, "Whoa, let's go," said Gaffney. Then, on November 22, 1963, Gaffney was sent on a new mission. “The colonel came down and he said, ‘You, you, you and you,’ and he started picking people out. He said Jacqueline Kennedy has requested Special Forces people in the honor guard,” said Gaffney. Gaffney was one of 21 chosen to stand guard over the casket in 30-minute shifts. Green Berets stayed with the casket all the way to the grave and remained on guard after the Kennedy family had left. Then, in an act that symbolized all JFK had done for Special Forces, one of them left his beret right next to the eternal flame. John F Kennedy and Vietnam John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) was the 35th president of the United States. Elected in 1960 at the age of 43, he became the youngest person ever to be voted into the White House. Kennedy served from 1961 until his assassination in November 1963. To this day, many Americans remember Kennedy as an idealistic champion of freedom at home and abroad, despite the fact that his policies on civil rights, Vietnam, and Cuba sometimes failed to live up to his soaring rhetoric. During his years as president, Kennedy tripled the amount of American economic and military aid to the South Vietnamese and increased the number of U.S. military advisors in Indochina. He refused to withdraw from the escalating conflict in Vietnam because, he said, "to withdraw from that effort would mean a collapse not only of South Vietnam, but Southeast Asia. So we are going to stay there." Some historians allege that just weeks before Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, he supported a military coup that overthrew and murdered South Vietnam's president Ngo Dinh Diem. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was a fervent believer in containing communism. In his first speech on becoming president, Kennedy made it clear that he would continue the policy of the former President, Dwight Eisenhower, and support the government of Diem in South Vietnam. Kennedy also made it plain that he supported the ‘Domino Theory’ and he was convinced that if South Vietnam fell to communism, then other states in the region would as a consequence. This Kennedy was not prepared to contemplate. Kennedy received conflicting advice with regards to Vietnam. Charles De Gaulle warned Kennedy that Vietnam and warfare in Vietnam would trap America in a “bottomless military and political swamp”. This was based on the experience the French had at Dien Bien Phu, which left a sizeable psychological scar of French foreign policy for some years. However, Kennedy had more daily contact with ‘hawks’ in Washington DC who believed that American forces would be far better equipped and prepared for conflict in Vietnam than the French had been. They believed that just a small increase in US support for Diem would ensure success in Vietnam. The ‘hawks’ in particular were strong supporters in the ‘Domino Theory’. Also Kennedy had to show just exactly what he meant when he said that America should: “Pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend…to assure the survival and success of liberty ”. In 1961, Kennedy agreed that America should finance an increase in the size of the South Vietnamese Army from 150,000 to 170,000. He also agreed that an extra 1000 US military advisors should be sent to South Vietnam to help train the South Vietnamese Army. Both of these decisions were not made public as they broke the agreements made at the 1954 Geneva Agreement. It was during Kennedy’s presidency that the ‘Strategic Hamlet’ programme was introduced. This failed badly and almost certainly drove a number of South Vietnamese peasants into supporting the North Vietnamese communists. This forcible moving of peasants into secure compounds was supported by Diem and did a great deal to further the opposition to him in the South. American television reporters relayed to the US public that ‘Strategic Hamlet’ destroyed decades, if not hundreds, of years of village life in the South and that the process might only take half-a-day. Here was a super-power effectively orchestrating the forced removal of peasants by the South Vietnamese Army who were not asked if they wanted to move. To those who knew about US involvement in Vietnam and were opposed to it, ‘Strategic Hamlet’ provided them with an excellent propaganda opportunity. Kennedy was informed about the anger of the South Vietnamese peasants and was shocked to learn that membership of the NLF had increased, according to US Intelligence, by 300% in a two year time span – the years when ‘Strategic Hamlet’ was in operation. Kennedy’s response was to send more military advisors to Vietnam so that by the end of 1962 there were 12,000 of these advisors in South Vietnam. As well as sending more advisors to South Vietnam, Kennedy also sent 300 helicopters with US pilots. They were told to avoid military combat at all costs but this became all but impossible to fulfil. Kennedy’s presidency also saw the response to the Diem government by some Buddhist monks. On June 11th 1963, Thich Quang Duc, a Buddhist monk, committed suicide on a busy Saigon road by being burned to death. Other Buddhist monks followed his example in August 1963. Television reported these events throughout the world. A member of Diem’s government said: “Let them burn, and we shall clap our hands.” Another member of Diem’s government was heard to say that he would be happy to provide Buddhist monks with petrol. Kennedy became convinced that Diem could never unite South Vietnam and he agreed that the CIA should initiate a programme to overthrow him. A CIA operative, Lucien Conein, provided some South Vietnamese generals with $40,000 to overthrow Diem with the added guarantee that the US would not protect the South Vietnam leader. Diem was overthrown and killed in November 1963. Kennedy was assassinated three weeks later. Alliance for Progress and Peace Corps, 1961–1969 Growing out of the fear of increased Soviet and Cuban influence in Latin America, the 1961–1969 Alliance for Progress was in essence a Marshall Plan for Latin America. The United States pledged $20 billion in assistance (grants and loans) and called upon the Latin American governments to provide $80 billion in investment funds for their economies. It was the biggest U.S. aid program toward the developing world up to that point—and called for substantial reform of Latin American institutions. President John F. Kennedy greeting Peace Corps volunteers. (John F. Kennedy Library) Washington policymakers saw the Alliance as a means of bulwarking capitalist economic growth, funding social reforms to help the poorest Latin Americans, promoting democracy—and strengthening ties between the United States and its neighbors. A key element of the Alliance was U.S. military assistance to friendly regimes in the region, an aspect that gained prominence with the ascension of President Lyndon B. Johnson to power in late 1963 (as the other components of the Alliance were downplayed). The Alliance did not achieve all its lofty goals. According to one study, only 2 percent of economic growth in 1960s Latin America directly benefited the poor; and there was a general deterioration of United States-Latin American relations by the end of the 1960s. Although derided as “Kennedy’s Kiddie Corps” by some when it was established in 1961, the Peace Corps proved over time to be an important foreign policymaking institution. By sending intelligent, hard-working, and idealistic young Americans to do economic and social development work (on 2-year tours) in the areas of greatest need in the Third World, the Peace Corps provided a means by which young Americans could not only learn about the world, but promote positive change. A significant number of Peace Corps Volunteers went on to work as officials in the U.S. Government. The Peace Corps remains an important, vibrant foreign policy institution. Since the Peace Corps’ founding, more than 187,000 men and women have joined the Peace Corps and served in 139 countries. There are 7,749 Peace Corps Volunteers currently serving 73 countries around the world. John F. Kennedy: Bay of Pigs In the spring of 1960, almost a year before Jack was sworn into office, President Eisenhower approved a CIA plan to secretly train anticommunist Cuban exiles to launch an invasion to overthrow Fidel Castro's government in Cuba. A mere two days after his inauguration, JFK was briefed on the plan. The CIA was anxious to take swift action in Cuba, fearing the rise of a dangerous communist regime only ninety miles from American soil, and urged Jack to authorize an invasion. Kennedy was ambivalent: while a successful invasion would topple Castro's anti-American government, a failed mission could be disastrous for Kennedy's image, both at home and abroad. After the CIA assured Jack that the "invasion force could be expected to achieve success," and that the United States would be only minimally implicated in the operation, Jack authorized the plans to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs.21 The mission was set to commence on 15 April 1961 with a military strike against Cuban airfields. Unfortunately for Kennedy, news of the impending invasion—as well as the United States' involvement in organizing the operation— was leaked in several American newspapers. On 12 April, Kennedy lied when publicly denying claims that the United States was planning or supporting an invasion of Cuba, but the damage was done: details of the plan had been exposed and Kennedy's administration was heavily implicated. The newspaper leak was only the first in a series of missteps, miscalculations, and unlucky developments that plagued the Bay of Pigs invasion from the beginning. For starters, the air strike on 15 April was a failure (only five of Castro's 36 planes were destroyed), leaving the invasion force totally exposed to Cuban air attack.22 When the 1,400 Cuban exiles began their amphibious invasion on 17 April, they were met on the beach by a strong, highly organized Cuban army. Though the CIA had anticipated a relatively easy overthrow of the Cuban government, the reality of the situation was starkly different. Jack and his advisers in Washington soon lost hope and by 18 April, the mission had clearly failed. In the end, 1,200 Cuban exiles were captured (and remained in captivity for 20 months) and 100 were killed.23 The Bay of Pigs disaster was an embarrassment for the new president, and arguably, the lowest point in Jack's political career. Jackie noted that on 19 April, Jack was "upset all day and had practically been in tears"—never before had she seen him so depressed.24 Kennedy's support of the Bay of Pigs invasion ran contrary to the idealistic rhetoric of his campaign, and his middle-of-the-road approach (agreeing to support the invasion, but doing so under a veil of secrecy) disappointed politicians on both ends of the political spectrum. More than anything, Jack felt that the bungled mission in Cuba confirmed the belief—held by his detractors—that he was too young and inexperienced to handle complex foreign policy issues. Throughout the remainder of his presidency, Jack was haunted by the mistakes made in the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Strangely enough, however, Kennedy continued to demonstrate the same kind of political ambivalence in future Cold War conflicts. In Laos, he refused to send in American troops, instead supporting a cease-fire that failed to quell the Communist insurgency. In Vietnam, he was again reluctant to fully commit U.S. troops, but refused to stay out of the situation entirely. As with the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy took the middle road, sending a contingent of military advisers to the region and hoping that this minimal intervention would yield positive results. Unfortunately, JFK's indecisiveness only made things worse; the deployment of American military advisers in Vietnam entangled the United States in a deadly conflict that would ultimately last for more than a decade. When Lyndon B. Johnson succeeded Kennedy as president, he inherited a seemingly no-win situation in Vietnam. Two months after the Bay of Pigs, Jack had regained confidence and was set to meet in Vienna with Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union. Looking to prove himself as a formidable world leader, Jack planned to speak with Khrushchev, a man known for his frankness and imposing demeanor, about improving Soviet-American relations. The Vienna Summit convened on 3 June 1961; the meeting would later stand as a defining—but not necessarily shining—moment in Kennedy's presidency. Khrushchev was quick to criticize American foreign policy, championing communist revolution in Southeast Asia and characterizing the United States as an oppressive force in world politics. Jack, outmaneuvered by the Soviet ruler's sharp tongue, had difficulty articulating the message he had come to deliver. That night, Jack was furious both with Khrushchev ("he treated me like a little boy") and with himself.25 Kennedy and Khrushchev met again the next day, and although Jack was able to hold his own better this time, the two-day conference had drawn into question Jack's perceived leadership, both domestically and internationally. Upon his return to the United States, Jack sought to restore his image as a foreign policy leader. In August of 1961, Kennedy proposed a nearly $10 billion increase for the national defense budget and the addition of 200,000 military personnel to the U.S. Armed Forces.26 Kennedy's hawkish proposal was a political success; Americans rallied behind the president's decisive anticommunist actions and seemed to forget his ill-fated meeting with Khrushchev. JFK's progressive domestic programs also helped to buffer the negative effects of his initial Cold War errors. Early in his presidency, Kennedy established the Peace Corps, an organization that sent young Americans to third-world countries in an effort to promote development and spread a message of understanding throughout the international community. The Corps was an immediate success, particularly among young people eager to heed Jack's inaugural call to "ask what you can do for your country." Kennedy also demonstrated his forward thinking in a 1961 address to Congress in which he proposed increased spending for space exploration. Following the Soviet Union's successful launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957 and Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin's orbit of the earth in 1961, Kennedy felt great pressure to compete with the Russians in exploring space, the final frontier. He believed that a successful space program—most importantly, a program that would allow the United States to become the first country to put a man on the moon—would increase America's power and prestige in the world (he was right, by the way). JFK and the Berlin Wall At the end of World War II, the main Allied powers—the United States, France, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union—divided Germany into two zones. The Soviet Union occupied East Germany and installed a rigidly controlled communist state. The other three Allies shared the occupation of West Germany and helped rebuild the country as a capitalist democracy. The City of Berlin, located 200 miles inside East Germany, was also divided. Half of the city—West Berlin—was actually part of West Germany. Many East Germans did not want to live in a communist country and crossed into West Berlin, where they could either settle or find transportation to West Germany and beyond. By 1961, four million East Germans had moved west. This exodus illustrated East Germans' dissatisfaction with their way of life, and posed an economic threat as well, since East Germany was losing its workers. A Summit with the Soviets In June 1961, President John F. Kennedy traveled to Vienna, Austria, for a summit with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Not only was the summit unsuccessful in its goal of building trust, but it also increased tensions between the two superpowers—particularly in discussions regarding the divided city of Berlin. During the summit, Khrushchev threatened to cut off Allied access to West Berlin. Kennedy was startled by Khrushchev's combative style and tone and unsettled by the threat. In an address to the American people on July 25, President Kennedy announced that the United States might need to defend its rights in Berlin militarily: "So long as the communists insist that they are preparing to end by themselves unilaterally our rights in West Berlin and our commitments to its people, we must be prepared to defend those rights and those commitments. We will at times be ready to talk, if talk will help. But we must also be ready to resist with force, if force is used upon us. Either alone would fail. Together, they can serve the cause of freedom and peace." President Kennedy ordered substantial increases in American intercontinental ballistic missile forces, added five new army divisions, and increased the nation's air power and military reserves. The Berlin Wall In the early morning hours of August 13, 1961, the people of East Berlin were awakened by the rumbling of heavy machinery barreling down their streets toward the line that divided the eastern and western parts of the city. Groggy citizens looked on as work details began digging holes and jackhammering sidewalks, clearing the way for the barbed wire that would eventually be strung across the dividing line. Armed troops manned the crossing points between the two sides and, by morning, a ring of Soviet troops surrounded the city. Overnight, the freedom to pass between the two sections of Berlin ended. Running across cemeteries and along canals, zigzagging through the city streets, the Berlin Wall was a chilling symbol of the Iron Curtain that divided all of Europe between communism and democracy. Berlin was at the heart of the Cold War. In 1962, the Soviets and East Germans added a second barrier, about 100 yards behind the original wall, creating a tightly policed no man's land between the walls. After the wall went up, more than 260 people died attempting to flee to the West. Though Kennedy chose not to challenge directly the Soviet Union's building of the Berlin Wall, he reluctantly resumed testing nuclear weapons in early 1962, following the lead of the Soviet Union. "Let Them Come to Berlin' In the summer of 1963, President Kennedy visited Berlin and was greeted by ecstatic crowds who showered his entourage with flowers, rice, and torn paper. In the Rudolph Wilde Platz, Kennedy gave one of his most memorable speeches to a rapt audience: "There are many people in the world who really don't understand, or say they don't, what is the great issue between the free world and the Communist world. Let them come to Berlin. There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin. And there are some who say in Europe and elsewhere we can work with the Communists. Let them come to Berlin. And there are even a few who say that it is true that communism is an evil system, but it permits us to make economic progress. Lass'sie nach Berlin kommen. Let them come to Berlin." No other American politician had met with such joy and enthusiasm on a visit to Germany. Shortly after President Kennedy's death in November of 1963, the square where he had made his famous speech was renamed the John F. Kennedy Platz. The Berlin Wall: 1961-1989 The construction of the Berlin Wall did stop the flood of refugees from East to West, and it did defuse the crisis over Berlin. (Though he was not happy about it, President Kennedy conceded that “a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.”) Over time, East German officials replaced the makeshift wall with one that was sturdier and more difficult to scale. A 12-foot-tall, 4-foot-wide mass of reinforced concrete was topped with an enormous pipe that made climbing over nearly impossible. Behind the wall on the East German side was a so-called “Death Strip”: a gauntlet of soft sand (to show footprints), floodlights, vicious dogs, trip-wire machine guns and patrolling soldiers with orders to shoot escapees on sight. In all, at least 171 people were killed trying to get over, under or around the Berlin Wall. Escape from East Germany was not impossible, however: From 1961 until the wall came down in 1989, more than 5,000 East Germans (including some 600 border guards) managed to cross the border by jumping out of windows adjacent to the wall, climbing over the barbed wire, flying in hot air balloons, crawling through the sewers and driving through unfortified parts of the wall at high speeds.