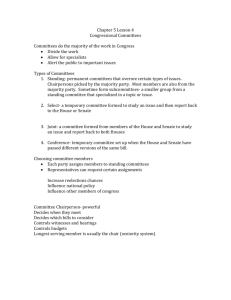

State Legislative Committees

State & Local Government

L E G I S L A T I V E C O M M I T T E E S

Legislative committees

“We are ruled by a score and a half of 'little legislatures’” – James Q. Wilson

Polsby: committees are a necessary component of institutionalization

Transaction costs are reduced through specialization & division of labor

Polsby & Committees

1.

2.

3.

4.

The committee system illustrates several of the key aspects of institutionalism that Polsby identified:

Committee jurisdictions provide a narrow scope of issues which committee members can specialize in as well as defining the turf it will defend from potential usurpurers.

It consists of numerous well-defined, issue-specific jurisdictions as well as special jurisdictions, such as the House Rules committee (where rules are established for floor debate), hence the committee system is complex.

Membership on committees is well-defined, restricted to members of Congress, and seats on committees are determined procedurally, hence the committee system is well-bounded.

Finally, the procedures and rules that govern behavior on the committee and within the legislature in relation to the committees illustrate the universalistic character of the committee system.

Thinking about Committees

Fenno (1973) proposed several important questions about committees:

why do members organize into committees?

What motivates members to work within committees?

What power and influence do they have in the chamber

Black’s study of committees provided a deductive model wherein voters (committee members) are the key actors choosing from policy alternatives represented in Euclidian space (Black 1948b; Black

1958)

Black rediscovers Condorcet

Duncan Black rediscovers the principle of rational behavior in committees as once articulated by

Condorcet when studying voting.

Condorcet argued that a “winner” is (or should be) the candidate or policy that beats all other candidates or policies in pair-wise competition.

The “Condorcet winner” is named for the eighteenth century mathematician and philosopher Marie Jean

Antoine Nicolas Caritat, the Marquis de Condorcet.

Condorcet Method

Rank the candidates or policies in order (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) of preference. Tie rankings are allowed, which express no preference between the tied candidates or policies.

Comparing each candidate on the ballot or policy on the agenda to every other, one at a time (pairwise), tally a "win" for the victor in each match.

Sum these wins for all ballots cast. The candidate or policy who has won every one of their pairwise contests is the most preferred, and hence the winner of the election.

In the event of a tie, use a resolution method (there are many possibilities).

A particular point of interest is that it is possible for a candidate to be the most preferred overall without being the first preference of

any voter. In a sense, the Condorcet method yields the "best compromise" candidate, the one that the largest majority will find to be least disagreeable, even if not their favorite.

Condorcet & Committees

Black realized that committees have trouble producing winners…as policies did not meet the Condorcet criterion: there was always a policy that could beat another policy.

The voting paradox (also known as Condorcet's paradox or the paradox of voting) is a situation noted by the Marquis de

Condorcet in the late 18th century, in which collective preferences can be cyclic (i.e. not transitive), even if the preferences of individual voters are not.

This is paradoxical, because it means that majority wishes can be in conflict with each other. When this occurs, it is because the conflicting majorities are each made up of different groups of individuals. For example, suppose we have three candidates, A, B and C, and that there are three voters with preferences as follows (candidates being listed in decreasing order of preference):

Cycling

Voter 1: A B C

Voter 2: B C A

Voter 3: C A B

If C is chosen as the winner, it can be argued that B should win instead, since two voters (1 and 2) prefer

B to C and only one voter (3) prefers C to B.

However, by the same argument A is preferred to B, and C is preferred to A, by a margin of two to one on each occasion. The requirement of majority rule then provides no clear winner.

The problem of Disequilibrium

Riker on Single-Peaked Preference Orderings

McKelvey’s Chaos Theory

• McKelvey’s chaos theorem suggests that the cycling problem is endemic to committees…that cycling will be prolific and eternal where n > 3 & m > 3.

Equilibrium with 2 Voters

Equilibria with 2 Voters

Riker Illustrates McKelvey

Another problem: Sophisticated Voting

Strategic voting occurs when a voter does not vote his or her true or “sincere” preference, in the hopes that a false one will get a better result. All the methods that people suggest adopting (including plurality) have some element of strategy. Ranked Pairs is no exception.

The most common example of strategic voting is the one from plurality. A voter may vote not for their first choice, but for a later choice they believe is more likely to win.

This is called the compromising strategy. For example, if the true rankings of the voters are:

Sophisticated (strategic) Voting

45 ABC

12 BAC

13 BCA

35 CBA

Then, if the voters all vote for their first choice, the result is:

A 45

B 25

C 35

A wins. However, if the BCA voters all voted for C, then C would win:

A 45

B 12

C 47

Of course, the BAC voters could cause A to win by voting A.

A 57

B 47

Agenda Control

The possibility of strategic voting means agenda control is important: the order that policies are considered can affect the final results.

Rep. Dingel: “If you let me write the procedure, and

I let you write substance, I’ll screw you every time.”

Institutions (i.e. rules matter): Setting the rules for the consideration of polices (i.e. the “agenda setter”) can influence what policies win irrespective of the underling preference ordering.

The answer to Riker’s question: “Why all the stability?” -- Institutions.

Procedural Choice in Committees

Procedural choice is the subject of the three models that will be developed here: the distributive model, the informational model, and the party cartel model.

Each of these theories posit different expectations as to how procedures are chosen in a legislature and how these choices effect the composition and outputs of legislative committees.

Distributional Model

The distributive model is rooted in the electoral incentives of the members of committee (Mayhew 1974; Fiorina 1977;

Shepsle and Weingast 1987).

This relates specifically to the issue of committee assignment: which members of the legislature will sit on which committees?

The distributive perspective provides that the members of

Congress most interested in the policy areas that fall within a particular committee’s jurisdiction will seek assignment to that committee.

Their interest derives from the interests of their constituents in their districts. Hence congresspersons from districts with a significant agricultural economic base will see assignment to committees that focus on issues relating to agriculture.

Distributional Committees

This implies two important expected empirical regularities for committees:

homogeneity preference outliers.

The first regularity is evident from the electoral incentive, committees should be composed of only those members with a significant district stake in the issue.

Committee members self-select on to the committee and this selection is dependent on the importance of the issue the committee has jurisdiction over.

Thus, they should be from similar districts, with similar constituents, and, indeed, may share regional and demographic characteristics.

Distributional Committees

The second regularity follows from the first, since these members have a larger stake in the issue should be high-demanders (preference outliers) when compared to the rest of the legislature, and hence engage in logrolling (I’ll vote for your X if you’ll vote for my Y) that the committee system, through restrictive rules and jurisdictional consideration, protects from the floor.

In other words, returning to the agricultural example, since the committee is composed of members from farm districts, it should be expected that their preferences regarding, say, farm subsides, are significantly different

(i.e. higher spending preferences) from the rest of the legislature.

The result is high-demand committees composed of preference outliers.

On any particular issue the legislature as a whole, relatively disinterested, trades away its ‘right to decide’ to demanding committees composed of legislators for whom this issue is of high importance. This view of committees is inherent to the problems with lawmaking identified by early scholars in regards to the ever-increasing budget and lack of fiscal responsibility (Mayhew 1974; Fiorina 1977).

Informational Committees

However, an important rebuttal perspective has been developed in recent years, most prominently by Keith

Krehbiel (Krehbiel, Shepsle et al. 1987; Gilligan and Krehbiel

1990; Krehbiel 1990; Krehbiel 1991; Baron 2000) that relies on the formal theoretic innovation of incomplete information.

Rather than an electoral incentive as the foundational basis for committee organization, they posit that committees serve an informational incentive.

Committees serve the floor (rather than vice versa) by providing the public good of expertise.

The important distinction that Krehbiel makes here is between the policies produced by government and the outcomes of these policies. Constituents (and thus members of the legislature), care about outcomes…not policies.

Informational Committees

Hence members have well defined preferences over outcomes and not policies.

However, legislators are uncertain as to what outcome X` will result from policy X. Hence, there is an incentive to produce information as to the relationship between policies and outcomes.

This is the public good that committees serve, according to Krehbiel: producing policy expertise. Krehbiel’s theory puts the distributive expectations in sharp relief.

Committees, rather than homogenous and preferenceoutlying, will be heterogeneous in nature and representative of the legislature itself (Krehbiel 1991).

Party Cartel Models

The third perspective on committees represents one of the more fundamental issues of disagreement in political science: the role of parties in politics.

The party cartel model, developed primarily by Cox and

McCubbins, posits that the traditional view of autonomous committees subservient to the demands of the interests and preferences of individual members of congress is at odds with the powerful role played by parties in establishing the procedural rules of congress and in making committee assignments.

Committee assignments are ‘stacked’ by the parties to serve partisan goals rather than the goals of individual legislators.

With the power to create, destroy, merge, and extend the jurisdictional power of committees, parties can exercise control over the policy produced by committees.