Day2

advertisement

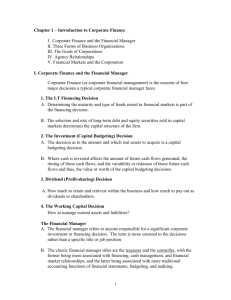

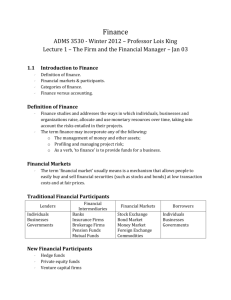

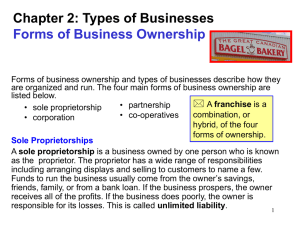

Ethics in the corporation What is a corporation? There are two main views: 1. 2. Corporations are legal creations, fictional persons with no emotions, intelligence, or will. Their legal personality is narrow, directed to one end only: generating wealth for their owners. (Tönnies; Chief Justice Marshall) Corporations are very much like people or communities and may be treated as such. Likewise, the people who run them carry the responsibility of the corporate direction and must be accountable for its “state of mind”. (Lord Denning) Chief Justice Marshall, Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 1819 “A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in the contemplation of the law. Being the mere creature of law, it possesses only those properties … as are best calculated to effect the object for which it was created.” (quoted by De George, 122) Denning L.J in H.L. Bolton (Engineering) Co. Ltd. v T.J. Graham & Sons Ltd [1951] 1 Q.B. 159 at 172. A company may in many ways be likened to a human body. It has a brain and nerve centre which controls what it does. It also has hands which hold the tools and act in accordance with directions from the centre. Some of the people in the company are mere servants and agents who are nothing more than hands to do the work and cannot be said to represent the mind or will. Others are directors and managers who represent the directing mind and will of the company, and control what it does. The state of mind of these managers is the state of mind of the company and is treated by the law as such. The joint stock company Allowed many contributors to pool their capital, usually with monopoly rights the Russia Company (1553) the East India Company (1600) the Hudson Bay Company (1670) Owners have liability to the extent of the fully paid up value of their shares. The price they pay is not having much say in the running or management of the company. Limited liability The Joint Stock Company Act 1856; Company Act 1862; House of Lords, Salomon v. Salomon & Co (1897) established the separate legal personality of the joint stock corporation. The liabilities of the company are not those of the owners, the shareholders. Exceptions do occur Where the courts believe that a corporation is being used as a front to evade contracts or statute law, they may lift the corporate veil. In Gilford Motor Co Ltd v. Horne (1933), the court found that Horne had formed a company to evade contractual obligations to a former employer and stopped that company from trading. How can ethics apply to a corporation? When the owners do not bear responsibility or liability for its acts? When responsibility is delegated to directors who are protected by a corporate veil? When a corporation is a legal instrument for achieving a limited range of objectives, principally profit? Can a corporation have a conscience? “Did you ever expect a corporation to have a conscience when it has no soul to be damned, and no body to be kicked?” First Baron Thurlow, Chancellor of England, c1600. A corporation can commit crimes and it can be punished. But can it be unethical? Ethical standards for corporations Let us grant that corporations are legal persons. Are they only legal entities? If corporations should observe legal standards, why should not they observe ethical ones? Corporations act, so why should not they act according to ethical standards? Two replies Philosophers argue about whether an organisation can act. Pragmatically, the law and people do regard corporations as actors, and the latter make moral judgments about corporate conduct. Making moral judgments about corporations is intelligible and often persuasive. Corporate morality limited Corporations have a different moral status from natural persons. Their moral obligations are fewer. They can still be held accountable and liable. Those within them can be held accountable and responsible. The ethics of role Role adds specific responsibilities: • Father/mother; citizen; occupation Role requires more of a person. Following directions is a valid reason for acting as long as those directions are ethical. What about role could exempt from ordinary moral requirements? Is it a particular place in the hierarchy of the organisation: • • • • Just following the orders of superiors? Others would do the same thing in my place? This is acceptable in this organisation? Somebody had to use their authority to save the company? • My actions were necessary in my position? Accountability the key Can the person with responsibility account satisfactorily for their actions? Even if there is an unsatisfactory aspect to these actions, were they done maliciously? Were the actions proportionate to the objective? Were other less harmful alternatives considered? The danger of double standards In corporations there are often two versions of reality: the one for external consumption (and accountability) and what actually happens. If the latter is too far from the former, people get the message that requirements for good practice are only for show and that they can cut corners. Societal Norms Organisational Counternorms •Be open & honest •Be secretive & deceitful •Conscientiously adhere to rules •Do whatever it takes to do the job •Use it or lose it •Be cost effective •Pass the buck •Take responsibility •Be a team player •Take credit for your own actions (& take credit for the actions of others, if you can) Accountability historical track tick the box reveals liability Responsibility proactive “take responsibility for” discretion ethical empowerment Stakeholder theory and the manager How are stakeholders to be ranked? The traditional view is to place owners the shareholders - first and last. A modern view demands that shareholders share their claims upon directors and managers with all those affected by the corporation’s operations. Corporate personality helps rank priorities The aims and purposes of the corporation (eg. articles of association) define its range of activities. Corporations - unlike natural persons - are not ends in themselves: they are not moral persons. Directors and managers are employees of the corporation, not of its shareholders. Directors have fiduciary duties to shareholders, but this does not exhaust their obligations. Conflict of interest: a case of understanding good judgment Corporate ethics is not about the corporation having a conscience; not about it “feeling good”; not about it being generous. Corporate ethics is about just conduct and avoiding unjust actions. It is about giving various stakeholders their due. Perhaps the biggest obstacle to this is conflict of interest. Conflict of Interest Conflict of interest being adversely affected by a conflict A person’s having a conflict of interest is not the same thing as a person’s being affected by a conflict of interest. “It’s a matter of where you draw the line.” Rather, some things are black, some things are white, and some things are grey. Good judgment Begins with the facts - as they are available. Is principled - expresses ethical principles. Is detached but not apathetic. Is committed but not fanatical. Respects the interests of others and can look at the issues from the viewpoint of others. In 2003, Johnson & Johnson Gave $99 million in cash to welfare organisations in the US and abroad. Gave $285.5 million in non-cash contributions. Gave a total of 3.7% of pretax profit to charitable causes - see the list in the report in the readings. Milton Friedman argues “Only people can have responsibilities.” Corporations can have responsibilities but not business in general. Why not? Executives are employees of “the owners of the business” and should act as they desire, namely to make as much money as possible. Is this true? Are not executives employees of the corporation? Friedman adds As the agent of others, he may not use their money for his purposes. Social responsibility implies that the manager will act contrary to the interests of shareholders. This robs them, may raise prices for customers, and may lower wages for workers. Individuals should spend their own money on socially worthy causes. If managers do this, they are “in effect imposing taxes”. Alan Greenspan agrees: “By law, shareholders own our corporations and, ideally, corporate managers should be working on behalf of shareholders to allocate business resources to their optimum use.” A stronger view “Business managers who use business funds for non-business purposes are guilty not just of the legal crime of theft, but of the … offence of teleopathy: in diverting funds from strictly business objectives to other purposes, they are pursuing the wrong ends. … when business pursues love - or ‘social responsibility’ - rather than money.” Elaine Sternberg. This is not the common view Friedman’s view might be theoretically correct but there is a practical problem: most people view corporations as more than wealth generators. The 1999 Millennium Poll on Corporate Social Responsibility of 25,000 consumers: “Two in three citizens want companies to go beyond their historical role of making a profit, paying taxes, employing people and obeying laws; they want companies to contribute to broader societal goals as well.” (PricewaterhouseCoopers) Andrew Carnegie “… the duty of a man of wealth (is) First, to set an example of modest, unostentatious living … to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him; and after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer … to produce the most beneficial results for the community … Philanthropy “Why can’t we encourage our major companies to put major dollars into healthcare? The Government can only do so much. I’m not critical of the Government. I’m critical of the corporations.” (Rosenfeld, W/end Aus. 2001) Professor Rosenfeld criticised drug companies for not investing in research on diseases prevalent in the Third World. Corporate giving Corporations were criticised for not giving generously to victims of the tsunami. They have been criticised for being difficult with insurance payouts, ungenerous with termination packages, for fighting legal actions vigorously. There is a general expectation in the West that they will give to charities. Shareholders’ Association view The Australian Shareholders Association has taken a tough line on charity. It believes companies should only give when there is an economic benefit to shareholders. Chief executive, Stuart Wilson, said: "In relation to the tsunami appeal I think it is quite appropriate for companies with suppliers, customers or operations in Asia to help the victims." The problem with philanthropy Directors and managers can confuse their generosity with the corporation’s: the corporation’s money does not belong to them Can raise expectations about the role of corporations and increase the costs of doing business. Businesses must remain competitive in order to serve any social purposes. The central issues in corporate giving are That directors can account for it That it is transparent That it is related to business purposes even if it is not central to those purposes That it does not harm the competitiveness of the business That is does not violate commutative or distributive justice Social costs and social responsibilities The operations of business incur social costs. Often those costs are paid socially as negative externalities rather than included in the price of products. This contravenes principles of fairness and distributive justice. Justice requires that Businesses compete on an equal footing Social resources not be regarded as free That use of social resources should reflect their cost and especially their cost to third parties That business engage in socially responsible conduct as a cost of doing business Triple bottom line reporting (Term coined by John Elkington in1997) To the financial statements attesting to the financial health of a corporation, 3BL adds environmental and social performance. Is a measure of general sustainability of a corporation’s operations. In order to have a long term future: • It must be profitable • It must minimise environmental impacts • It must meet social expectations The Merck case 1979, a Merck scientist has a hunch that one of their products could cure river blindness. Cost of development is > $100 million. Risk of undermining veterinary product. Drug market was crowded and margins were shrinking. No distribution networks where drug most needed. No clear market for product. U.S. Govt. and WHO would not fund it. Should Merck develop the drug?