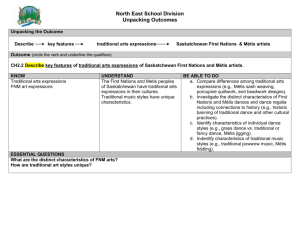

contents - Metis National Council

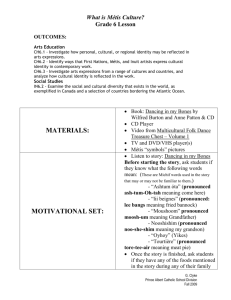

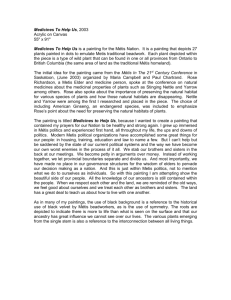

advertisement