Ashley Pierce

advertisement

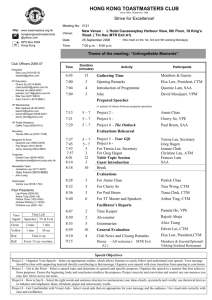

COUPLING CHEMICAL TRANSPORT MODEL SOURCE ATTRIBUTIONS WITH POSITIVE MATRIX FACTORIZATION: APPLICATION TO TWO IMPROVE SITES IMPACTED BY WILDFIRES Sturtz et. al. 2014 ATMS 790 seminar Ashley Pierce OUTLINE Background Source Apportionment Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) Chemical Transport Model (CTM) Hybrid The study Model comparison and evaluation Implications 2 BACKGROUND Particulate matter (PM2.5): mixture of small particles and liquid drops Aerosol: PM suspended in a gas (e.g. air) Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): variety of chemicals (benzene, isoprene) Secondary Organic Aerosols (SOA) Carbonaceous aerosols – major component of fine particulate mass IMPROVE: Interagency Monitoring of Protected Visual Environments (1985) National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) 3 SOURCE APPORTIONMENT Primary & secondary pollutants Transport, transformation, & removal processes Primary pollutants Transport, transformation, & removal processes Primary & secondary pollutants Emission Source Receptor (Anthropogenic combustion, biomass burning, biogenic emissions from plants) Affected site/organism or measurement area Source-Receptor relationship: determining the role of meteorology and physical/chemical effects linking source emissions to receptor concentrations Source profiles: the experimentally determined unique proportion of species concentrations 4 (or speciated PM or speciated aerosol) from a source Ex. Biomass burning – OC, EC, levoglucosan Feature: A factor profile (source factor) unique proportion of speciated aerosols determined by the PMF analysis PARTICULATE CARBON Fossil carbon: coal, oil, gas fuels Biogenic carbon: biomass burning, meat cooking, Secondary organic aerosols (SOAs) Upper bound for biomass burning contribution 5 More volatile, lower light absorption Higher light absorption 6 http://www.lucci.lu.se/wp1_projects.html IMPORTANCE Adversely affect health, contribute to haze, affect radiation balance Biogenic sources of carbonaceous aerosols 80-100% of fine particulate carbon in rural areas ~50% in some urban areas Carbonaceous species often largest contributor to haze and PM2.5 Smoke thought to be large contributor (W and SE U.S.) Difficult to apportion smoke from other emissions or between smoke types >50% of smoke particulate mass can be secondary organic aerosol (SOA) Similar to SOA composition formed from gases emitted by plant respiration Biomass burning emissions inventories likely overestimate PM emissions, underestimate VOC emissions from biomass combustion and biogenic release 7 POSITIVE MATRIX FACTORIZATION (PMF) Multivariate factor analysis Uses matrix of speciated sample data Source contributions Source profiles Inputs: Species concentrations (𝑥𝑖𝑗 ) uncertainties (𝜎𝑖𝑗 ) number of sources (user−defined, 𝑝) Interpret source types: Source profile information Wind direction analysis Emission inventories 8 PMF DISADVANTAGES True source profiles not known (no emission info) Requires assumptions that are not always true Can’t apportion secondary organic aerosols to source types Factor profiles can have large errors and may correspond to a mixture of source types Uncertainties in measurements are not always known or well-defined 9 PMF ADVANTAGES Each data point can be weighted individually uncertainty value (𝜎𝑖𝑗 ) 𝑛 𝑚 𝑄= 𝑖=1 𝑗=1 𝑥𝑖𝑗 − 2 𝑝 𝑔 𝑓 𝑘=1 𝑖𝑘 𝑘𝑗 𝜎𝑖𝑗 Data below detection limit Variability in solution estimated by bootstrapping technique, “re-sampling” of data set Based on observations Don’t need source emissions Less uncertainty than CTM 10 CHEMICAL TRANSPORT MODEL (CTM) CAPITA Monte Carlo Lagrangian CTM Direct simulation of atmospheric pollutants Each emitted quantum contains a fixed quantity of mass for various pollutants based on the source emission rate Individual particles subjected to transport, transformation, and removal processes 6-day back trajectories of air masses using meteorological data from the Eta Data Assimilation System (EDAS) Non-fire emissions: Western Regional Air Partnership (WRAP) 2002 emissions inventory 11 Biomass burning: MODIS inventory Source profiles compiled from burns 12 CTM DISADVANTAGES Large information requirements Chemical mechanisms are incomplete Large errors and biases Particularly with wildfires Driven by emissions inventory Overall higher root mean square error (RMSE) than PMF and Hybrid 13 CTM ADVANTAGES Identification and separation of different source types based on emissions inventory Primary and secondary carbonaceous fine particles can be identified from source types biomass combustion, biogenic, mobile, area, oil, point, other 14 HYBRID Source-oriented Measured data used to constrain CTM Direct incorporation of measured data into model Post-processing of model results Receptor-oriented CTM results constrain receptor model (PMF) using Multilinear Engine-2 (ME-2) 15 MASS BALANCE 𝑥 – speciated sample data matrix with dimensions 𝑖 by 𝑗 𝑖 : number of samples 𝑗 : chemical species measured ε𝑖𝑗 - residual for each sample/species (model error) Want to identify: 𝑔𝑖𝑘 – amount of mass contributed by each source to each individual sample 𝑝 𝑓𝑘𝑗 – species profile of each source 𝑥 = 𝑔 𝑓 +ε 𝑝 – number of sources 𝑖𝑗 𝑖𝑘 𝑘𝑗 𝑘=1 No samples can have a negative source contribution 𝑔𝑖𝑘 and 𝑓𝑘𝑗 > 0 𝑖𝑗 16 THE STUDY Goal: Distinguish source contributions to total fine particle carbon Biogenic sources Biomass combustion due to wildfires Using a receptor-oriented hybrid model 17 SITES Speciated PM2.5 from Monture and Sula Peak Montana Three year: 2006-2008 Monture Sula 18 SPECIES Species with 0.2 ≤ S/N < 2.0 were down weighted by factor of 3 Removed species: S/N ratio <0.2 below detection limit missing > 50% samples Mass reconstruction outside IMPROVE limits 8% samples from Monture 25% samples from Sula Looked at 23 species 19 SOURCES Smallest value of 𝑝 where a change in the ratio of cross-validated 𝑄𝑚𝑖𝑛 to 𝑄𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑜𝑟𝑒𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 approaches zero User judgment based on qualitative agreement between the species profiles (𝑓𝑘𝑗 ) and prior knowledge of source profiles from known source types within the model region 20 Missoula paper mill & mining Gold, cobalt and Molybdenum mines Dry soils, Long-range Transport, Fires? 21 COMPARISON 22 SEASONS (CTM AND HYBRID) 23 Winter (Dec Jan Feb) Spring (Mar Apr May) Summer (Jun Jul Aug) Autumn (Sep Oct Nov) MODEL EVALUATION Root mean square error (RMSE) – measure of the differences between the value predicted by the model and the observed values Sample standard deviation of the differences between predicted and observed values Measure of accuracy 𝑅𝑀𝑆𝐸 = 𝑛 𝑡=1(𝑋𝑝 − 𝑋𝑜 )2 𝑛 Correlation coefficient (R) – measure of strength and direction of linear relationship between two variables The covariance of two variables divided by the product of their standard deviations 24 MODEL EVALUATION 25 MODEL EVALUATION 0.83 0.67 PMF γ = 0 CTM γ = 1 Monture γ = 0.83 Sula γ = 0.67 26 HYBRID DISADVANTAGES Still unable to distinguish between primary and secondary biomass combustion impacts CTM model predictions were highly correlated Equation 2 should account for multiplicative bias but does not work with high correlation and no tracer species Requires experts to run model in current form 27 HYBRID ADVANTAGES Complementary attributes from PMF and CTM Directly applying the CTM predictions to the PMF model allows for resolution of sources not identified by the PMF alone Biogenic vs. biomass combustion Theoretically primary and secondary features should be distinguishable 28 IMPLICATIONS Accurate identification of relevant sources and impact on receptors will guide control policy lower costs better results Ability to better distinguish sources to prove pollution events are due to exceptional events such as wildfires 29 REFERENCES Norris, G., & Vedantham, R. (2008). EPA Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 3.0 Fundamentals & user guide. Paatero, P. (1999). The Multilinear Engine—A Table-Driven, Least Squares Program for Solving Multilinear Problems, Including the n-Way Parallel Factor Analysis Model. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 8(4), 854-888. doi: 10.1080/10618600.1999.10474853 Polissar, A. V., Hopke, P. K., Paatero, P., Malm, W. C., & Sisler, J. F. (1998). Atmospheric aerosol over Alaska: 2. Elemental composition and sources. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 103(D15), 19045-19057. doi: 10.1029/98JD01212 Ramadan, Z., Eickhout, B., Song, X.-H., Buydens, L. M. C., & Hopke, P. K. (2003). Comparison of Positive Matrix Factorization and Multilinear Engine for the source apportionment of particulate pollutants. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 66(1), 15-28. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S01697439(02)00160-0 Schichtel, B., Fox, D., Patterson, L., & Holden, A. Hybrid Source Apportionment Model: an operational tool to distinguish wildfire emissions from prescribed fire emissions in measurements of PM2.5 for use in visibility and PM regulatory programs. Schichtel, B. A., & Husar, R. B. (1997). Regional Simulation of Atmospheric Pollutants with the CAPITA Monte Carlo Model. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 47(3), 301-333. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1997.10464449 Schichtel, B. A., & Husar, R. B. (1997). The Monte Carlo Model: PC-Implementation. Retrieved 02/16/15, 2015, from http://capita.wustl.edu/capita/CapitaReports/MonteCarloDescr/mc_pcim0.html Schichtel, B. A., Malm, W. G., Collett, J. L., Sullivan, A. P., Holden, A. S., Patterson, L. A., . . . Barna, M. G. (2008). Estimating the contribution of smoke to fine particulate matter using a hybrid-receptor model. Paper presented at the Air and Waste Management aerosol and atmospheric optics. Sturtz, T. M., Schichtel, B. A., & Larson, T. V. (2014). Coupling Chemical Transport Model Source Attributions with Positive Matrix Factorization: Application to Two IMPROVE Sites Impacted by Wildfires. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(19), 11389-11396. doi: 10.1021/es502749r 30 EXTRA 31 MULTILINEAR ENGINE-2 (ME-2) performs iterations via a preconditioned conjugate gradient algorithm until convergence to a minimum Q value 𝑛 𝑚 𝑄= 𝑖=1 𝑗=1 𝑥𝑖𝑗 − 2 𝑝 𝑔 𝑓 𝑘=1 𝑖𝑘 𝑘𝑗 𝜎𝑖𝑗 Conjugate gradient algorithm: algorithm for the numerical solution of particular systems of linear equations, usually a symmetric, positive-definite matrix 32 𝑛 𝑚 𝑄 = (1 − γ) 𝑖=1 𝑗=1 ε𝑖𝑗 𝜎𝑖𝑗 𝑛 2 𝑣 + (γ) 𝑖=1 𝑡=1 ε𝑖𝑡 𝜔𝑖𝑡 2 ε𝑖𝑡 𝜔𝑖𝑡 𝑤 2 + 𝑏 𝑐 𝑢𝑠 + 𝑠=1 𝑢𝑙𝑟 𝑙=1 𝑟=1 𝜎𝑖𝑗 : species measurement uncertainty 𝜔𝑖𝑡 : CTM uncertainty γ: user-defined weighting parameter for CTM predictions relative to mass balance model Residuals from Equations 1-2: Equation 1: Standard PMF chemical mass balance equation 𝑝 𝑥𝑖𝑗 = 𝑔𝑖𝑘 𝑓𝑘𝑗 + ε𝑖𝑗 𝑊ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑔𝑖𝑘 , 𝑓𝑘𝑗 > 0 𝑘=1 Equation 2: 𝑡 th CTM constraint: 𝑡 = 1, 𝑣 contributions 𝑔𝑖𝑡 to total fine particulate carbon predicted by the CTM model 𝑣 = 2 sources (total biomass combustion and biogenic emissions) 33 𝑔′𝑖𝑡 = 𝑔𝑖𝑡 𝐼𝑡 + ε′𝑖𝑡 𝑊ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑡 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑒𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑘 𝑛 𝑚 𝑄 = (1 − γ) 𝑖=1 𝑗=1 ε𝑖𝑗 𝜎𝑖𝑗 𝑛 2 𝑣 + (γ) 𝑖=1 𝑡=1 ε𝑖𝑡 𝜔𝑖𝑡 2 ε𝑖𝑡 𝜔𝑖𝑡 𝑤 2 + 𝑏 𝑐 𝑢𝑠 + 𝑠=1 𝑢𝑙𝑟 𝑙=1 𝑟=1 Prior source profile constraints: Equation 3: Normalized thermal fractions of carbon for each source. Rescales 𝑓 such that 𝑔𝑖𝑘 in eq. 1 and 2 represents total fine particle carbon and 𝑓𝑘𝑗 = mass fraction of species 𝑗 in source 𝑘 relative to total carbon 𝑤 𝑓𝑘𝑠 = 1 + 𝑢𝑠 𝑊ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑠 𝑐𝑎𝑟𝑏𝑜𝑛 𝑓𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑒𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑠=1 𝑗 𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑒𝑠 , 𝑢𝑠 = 0.001 Equation 4: Secondary feature profile constraint Primary biogenic source consists only of VOCs Sets all r=1 to c non-carbonaceous species near zero Biomass source: carbon thermal fractions, potassium, nitrate, sulfate, hydrogen 𝑓𝑙𝑟 = 0 + 𝑢𝑙𝑟 𝑊ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑙 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑒𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑘 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑟 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑠𝑒𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝑗 𝑠𝑝𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑒𝑠 , 𝑢𝑙𝑟 = 1 ∗ 10−5 34