The Financial Crisis and Regulatory Response

advertisement

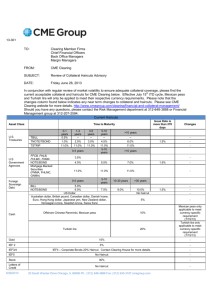

DERIVATIVES MARKETS: CROSS-BORDER REGULATION PREPARED FOR COLADE 2014: XXXIII CONGRESO LATINOAMERICANO DE DERECHO FINANCIERO NOVEMBER 20, 2014 STEPHEN M. HUMENIK Overview • • • • • • The Financial Crisis and Regulatory Response U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission The Dodd-Frank Act European Financial Reform Cross-Border Issues – CCP Recognition Covington - Key Attorney Profiles 2 THE FINANCIAL CRISIS AND REGULATORY RESPONSE 3 The Financial Crisis: International Reaction • In September 2009 the leaders of the Group of 20 (G-20)—whose membership includes the United States, the European Union, and 18 other countries—agreed to a five part framework for global OTC derivatives reform: 1. Central clearing of OTC derivatives; 2. Increased standardization of OTC derivatives; 3. Exchange trading of standardized derivatives; 4. Reporting derivatives trades to trade repositories, and 5. Increased capital requirements for non-cleared derivatives Argentina Australia Brazil Canada China France Germany India Indonesia Italy Japan Republic of Korea Mexico Russia Saudi Arabia South Africa Turkey United Kingdom United States European Union 4 U.S. COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION (CFTC) 5 The Commission • The CFTC is lead by 5 Commissioners – Nominated by President, “advice and consent” of the Senate Chairman Timothy Massad* • Controls agenda, serves at the pleasure of the President. Commissioner Mark Wetjen Commissioner Sharon Bowen Commissioner Christopher Giancarlo Commissioner (Vacancy) • The CFTC regulates: Futures – subject to CFTC regulation since the 1920s. Options on Futures – subject to CFTC regulation since the 1920s. Swaps – subject to CFTC regulation since the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act on July 21, 2010, effective July 21, 2011. Swaps include broad-based indices. Security-Based Swaps – single name CDS and narrow-based indices subject to SEC jurisdiction since the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act. Spot, cash, physical or forward transactions –transactions in the “cash market” – are exempt from CFTC regulation. 6 CFTC Operations • • • • • 680 Staff (2010-2012) 707 Staff (2013) 667 Staff (2014) • 1,015 Staff (proposed 2014) 920 Staff (2015 request) SEC had 3,958 (2012) Headquartered in DC with offices in New York, Chicago, Kansas City Division of Market Oversight Office of the Executive Director Division of Clearing and Risk Office of Public Affairs Office of International Affairs Office of Legislative Affairs Division of Enforcement Office of the General Counsel Office of the Secretariat Division of Swap Dealer and Intermediary Oversight Office of the Chief Economist Office of the Inspector General Office of Data and Technology 7 THE DODD-FRANK ACT 8 Clearing Clearing Swap Dealer Oversight Price Transparency Swaps Market Reform – Reduction of Systemic Risk Central clearing is one of the three major building blocks of Dodd-Frank swaps market reform -- in addition to promoting market transparency and bringing swap dealers under comprehensive oversight -- and this rule completes the clearing building block. Central clearing lowers the risk of the highly interconnected financial system. It also democratizes the market by eliminating the need for market participants to individually determine counterparty credit risk, as now clearinghouses stand between buyers and sellers. In a cleared market, more people have access on a level playing field. Small and medium-sized businesses, banks and asset managers can enter the market and trade anonymously and benefit from the market’s greater competition. Chairman Gensler, November 28, 2012 (Statement on Clearing Determinations). 9 Clearing Rules • DCO Core Principles, Risk Management • Protection of Cleared Swaps Customer Contracts and Collateral • Documentation, Straight Through Processing, and FCM Risk Management • Mandatory Clearing Determinations 10 Trading and Clearing Market Structure Executing Broker Asset Manager (Trader) on behalf of Customers Executing Broker (FCM) Exchange (DCM) or Swap Execution Facility || || Clearing House Executing Broker Executing Broker (FCM) Clearing Clearing Brokers (FCMs) Brokers (FCMs) Asset Manager (Trader) on behalf of Customers 11 DCO Core Principles • Section 725(c) of the Dodd-Frank Act amended Section 5b(c)(2) of the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA), sets forth core principles with which a DCO must comply to be registered and to maintain registration as a DCO. The DoddFrank Act revised the 14 existing core principles and added four new ones. – Financial resources – Participant and product eligibility – Risk management – Settlement procedures – Treatment of funds – Default rules and procedures – Rule enforcement – System safeguards – Reporting – Recordkeeping – Public information – Information sharing – Antitrust considerations – Legal risk considerations 12 DCO Core Principles – Risk Management • • • Core Principle D - Risk Management: – Regulation 39.13 sets forth the requirements that a DCO would have to meet to comply with Core Principle D. – The regulation addresses requirements for a DCO’s risk management framework (including margin methodology and coverage, price data, daily review and periodic back tests) and other risk control mechanisms (including risk limits, review of large trader reports, stress tests, and reviews of clearing members’ risk management policies and procedures). The Dodd-Frank Act also provides for additional regulation by the Federal Reserve of Systemically Important Derivatives Clearing Organizations or SIDCOs designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Counsel. In terms of DCOs, the following are SIDCOs: – Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Inc.; – ICE Clear Credit LLC; and, – The Options Clearing Corporation 13 SEGREGATION UNDER THE COMPLETE LEGAL SEGREGATION (LSOC) MODEL 14 15 Information Exchange and Regulation Under the CLS/LSOC Model Responsibilities of the DCO: 1) Take appropriate steps to confirm the information it receives from the DCO. 2) Ensure that the FCM is providing the DCO with the required information. DCO FCM An FCM must share with the DCO: • One time: Information sufficient to identify a customer. (This must only be done the first time the FCM intermediates a trade for a customer). • Daily: Information sufficient to identify the customer’s portfolio of rights and obligations. 16 Complete Legal Segregation (CLS) Same macro structure as Future Model DCO FCM Prop. Margin Account DCO Capital Account Omnibus Collateral Account (OCA) FCM FCM Customer Margin Account C1 (Hedge Fund) C2 (Trust) FCM Customers C3 (Pension Plan) Internal Structure of OCA C1 Collateral C2 Collateral C3 Collateral FCM Excess Collateral Difference is in the details: At the DCO level: • All collateral belonging to an individual cleared swaps customer (CSC) must be individually identifiable within the omnibus account (Reg 22.12). • DCOs are not permitted to use CSC collateral to margin, guarantee, or secure the obligations of the FCM or any other CSC (Reg 22.15). • Once per day DCOs must calculate and record: 1. the amount of customer collateral required for each FCM CSC. 2. The sum of CSC collateral in the omnibus account. At the FCM level • CSC collateral may continue to be comingled (Reg 22.2) but all customer collateral must be individually identifiable within the comingled account (Reg 22.12). • FCMs are mandated to use their own capital to cover the negative account balance of a CSC. FCMs may contribute to the Omnibus account in advance to preempt any account deficiencies (Reg 22.2). • FCMs are prohibited from imposing or permitting the imposition of a lien on all cleared swap collateral, including any residual financial interest which the FCM may have due to their individual contributions to the customer collateral 17 account (Reg 22.2). CLS(LSOC) in case of FCM Default FCM Customers Step 1. Customers post collateral to FCM. Step 2. FCM prop trades go against the FCM. Step 3. FCM withdraws excess collateral from OCA. Step 4. FCM fails to meet DCO margin call on its prop margin account. Step 5. DCO liquidates FCM prop margin account. Step 6. FCM customer funds in the OCA are ported to a solvent FCM. FCM 1. FCM Customer Collateral Account C1 C2 2. FCM Prop Trading Account C3 6. 3. DCO OCA C1 C2 C3 Excess Collateral DCO Capital 4. FCM prop trading margin account 5. The CLS model significantly enhances the transparency of the contents of the OCA. As such, any issue regarding the right of the FCM to collateral in the OCA will be more easily resolved. 18 Clearing & Trading Mandates • • Asset classes made subject to mandatory clearing, and, later, mandatory trading are: – Interest rates (certain products are subject to mandates) – Credit (certain products are subject to mandates) – Energy (expected) – NDFs (expected - the proposal could include India, Korea, China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan, the Philippines, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, Russia, and Peru – all against the US Dollar) Process for the Commission to make a clearing determination: – Rule proposal – 90 day review period, which includes a 30 day comment period – Consideration of comments and incorporation into a final rule – Finalization of the rule – Publication in the Federal Register and phasing: Category 1 Category 2 Category 3 – 90 days after publication, Category 1 entities must comply (SDs/MSPs and “Active Funds” (Private Funds trading 200+ swaps per month/past year) that are not “3rd party subaccounts) – 180 days after publication, Category 2 entities must comply (Commodity Pools, Private Funds that are not “Active Funds,” and people “predominantly engaged in” banking activities or activities that are financial in nature, that are not “3rd party subaccounts”) – 270 days after publication, Category 3 entities must comply (pension funds, “3rd party subaccounts,” and all others subject to the mandate) 19 MARKET PARTICIPANT OVERSIGHT 20 Market Participant Categories Swap Dealers • Holds itself out as a dealer in swaps; • Makes a market in swaps; • Regularly enters into swaps with counterparties as an ordinary course of business for its own account; or • Engages in any activity causing it to be commonly known in the trade as a dealer or market maker in swaps • Also referred to as “Dealers” or “Liquidity Providers.” • 105 Provisionally Registered • Examples: • Bank of America • Goldman Sachs • JPMorgan • Mizuho • Morgan Stanley • Wells Fargo • BP • Shell • Cargill (Limited Designation) Major Swap Participants • Not a swap dealer, and • Maintains a substantial position in swaps • 2 Provisionally Registered • Examples: • Cournot Financial Products LLC • MBIA Insurance Corporation Intermediaries Financial Entities Commercial End Users • Futures Commission Merchants (FCMs) • engaged in soliciting or in accepting orders for the purchase or sale of futures and swaps; • accepts any money, securities, or property to margin, guarantee, or secure any trades • Swap dealer or securitybased swap dealer; • Major swap participant or major security-based swap participant; • Commodity pool; • Private fund; • Employee benefit plan; • Banks (total assets of $10 billion or more) • Not a financial entity; • Using swaps to hedge or mitigate commercial risk; and • Notifies the CFTC how it meets its financial obligations associated with entering uncleared swaps • FCMs are also referred to as Clearing Firms or Clearing Members of a Derivatives Clearing Organization or Clearinghouse. • Examples • Hedge funds • Commodity pools • Insurance companies • Examples • Commodity producers • Energy companies • Introducing Brokers (IBs) • engaged in soliciting or in accepting orders for the purchase or sale of futures and swaps; 21 FCM Regulations • • • • • • • • • • • Segregation of Customer Funds Minimum Net Capital Disclosure Requirements Trade Authorization Requirements Reporting to Customers Diligent Supervision Prohibition on Fraud Financial and Other Filings Conflicts of Interest Chief Compliance Officer Recordkeeping 22 List of Top CFTC-registered FCMs Futures Com m ission Merchant / Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer JP MORGAN SECURITIES LLC GOLDMAN SACHS & CO DEUTSCHE BANK SECURITIES INC NEWEDGE USA LLC MORGAN STANLEY & CO LLC MERRILL LYNCH PIERCE FENNER & SMITH CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC UBS SECURITIES LLC BARCLAYS CAPITAL INC CITIGROUP GLOBAL MARKETS INC RJ OBRIEN ASSOCIATES LLC ADM INVESTOR SERVICES INC BNP PARIBAS PRIME BROKERAGE INC ABN AMRO CLEARING CHICAGO LLC INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC MIZUHO SECURITIES USA INC MERRILL LYNCH PROFESSIONAL CLEARING CORP JEFFERIES BACHE LLC RBS SECURITIES INC FCSTONE LLC ROSENTHAL COLLINS GROUP LLC MACQUARIE FUTURES USA LLC RBC CAPITAL MARKETS LLC BNP PARIBAS SECURITIES CORP HSBC SECURITIES USA INC JP MORGAN CLEARING CORP GOLDMAN SACHS EXECUTION & CLEARING LP WELLS FARGO SECURITIES LLC STATE STREET GLOBAL MARKETS LLC Net Capital Requirem ent $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 2,225,987,881 2,311,493,479 755,262,495 958,281,407 1,653,072,250 1,099,047,995 2,304,170,706 876,345,719 1,456,792,521 1,066,873,079 156,483,823 163,339,879 201,838,470 150,908,832 345,767,280 211,723,805 347,151,822 108,489,520 140,547,216 74,614,248 60,679,597 114,991,728 116,297,701 171,406,255 191,391,550 2,091,725,305 164,120,199 271,413,843 76,947,224 Excess Net Capital $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 10,883,514,614 11,527,007,399 8,875,442,405 861,486,268 7,680,037,243 8,942,537,322 4,770,063,381 7,259,274,347 6,004,429,331 4,398,024,976 46,737,499 123,615,270 3,164,708,355 249,435,218 1,833,790,558 258,467,515 1,564,089,137 79,873,480 4,600,489,797 47,583,067 20,821,657 54,929,292 995,989,050 1,498,606,024 806,064,054 5,752,729,204 1,421,728,778 2,514,788,129 465,296,670 Custom ers' Assets in Seg $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 19,393,368,514 18,874,745,143 12,999,496,611 12,753,294,665 10,886,038,710 10,501,298,494 9,774,124,491 7,692,991,261 6,643,497,184 5,563,434,675 4,202,187,210 3,531,779,270 3,041,050,765 2,671,721,876 2,414,483,081 2,369,259,573 2,207,983,214 1,910,329,000 1,833,800,437 1,783,248,016 1,628,252,443 1,545,664,637 1,319,707,639 1,195,432,954 1,162,196,222 1,129,987,543 1,129,117,950 1,089,002,931 931,436,912 Funds in Separate Cleared Sw ap Segregation $ 4,700,616,746 $ 2,907,864,893 $ 1,818,934,500 $ 547,752,676 $ 4,750,430,314 $ 2,384,290,305 $ 9,294,546,312 $ 1,108,237,481 $ 6,861,502,902 $ 5,783,154,955 $ $ 13,453,875 $ 10,831,500 $ $ $ 69,372,333 $ 1,000 $ 61,763,000 $ 178,816,125 $ $ $ 21,605,136 $ $ 430,744,592 $ 578,928,742 $ 250,000 $ $ 1,741,820,461 $ 415,689,660 23 PRICE TRANSPARENCY – REPORTING AND TRADING 24 Price Transparency Clearing Swap Dealer Oversight Price Transparency Swaps Market Reform – Reduction of Systemic Risk 25 Price Transparency • Swap Data Repositories • Swap Execution Facilities and Designated Contract Markets • Swap Block Trade Sizes “The more transparent a marketplace is, the more liquid it is for standardized instruments, the more competitive it is and the lower the costs for hedgers, borrowers and, ultimately, their customers.” - Remarks by Chairman Gary Gensler, Bringing Oversight to the Swaps Market, International Finance Corporation’s 13th Annual Global Private Equity Conference, Washington, DC (May 11, 2011) 26 EUROPEAN FINANCIAL REFORM 27 European Market Infrastructure Regulation - EMIR • • EMIR imposes: – an obligation on specific standardised OTC derivatives trades to be cleared through central counterparties; – risk mitigation techniques for OTC derivatives which are not centrally cleared; – a reporting obligation on all derivatives trades; – new rules on authorisation, as well as prudential, organisational and conduct of business rules for central counterparties; – a registration requirement, as well as operational and transparency obligations for trade repositories. EMIR applies to all European Economic Area (“EEA”) financial and non-financial counterparties which undertake trades in derivatives. Non-EEA counterparties may also be affected if they undertake trades and the transaction could have a ‘direct, substantial and foreseeable effect’ in the EEA. 28 European Market Infrastructure Regulation - EMIR • • • EMIR came into force on 16 August 2012. EMIR’s reporting obligations came into effect on 12 February 2014 for all types of derivative contracts. Other issues which have yet to be finalised are: – the clearing obligation, which is unlikely to take effect until 2015; – variation margin requirements for uncleared trades, which are expected to be in force from 1 December 2015. – initial margin requirements will not be fully in force until 1 December 2019. 29 MiFID II and MiFIR • • • On 22 May 2014, the European Securities and Markets Authority (“ESMA”) published a Discussion Paper (ESMA/2014/548) and Consultation Paper (ESMA/2014/549), which together herald the launch of its consultation process for the implementation of the recast Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (“MiFID II”) and Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (“MiFIR”). The publication of these two documents represents the first step in the process of translating the recently agreed texts of the MiFID II and MiFIR requirements into practical rules and regulations. 30 MiFID II and MiFIR • Both the Discussion Paper and Consultation Paper cover many of the same topics, including: – Commodity Derivatives (including position limits) – Open Access (access to central counterparties, trading venues and benchmarks) – Market Infrastructure (requirements for organisation of new trading venues and impact of the new obligation to trade on those venues) – Investor Protection – Algorithmic and High Frequency Trading (defining terms and regulating activities) – Third Country Access (treatment of third country firms accessing EU customers) – Reporting of Instruments – Transparency Requirements for Instruments 31 CROSS-BORDER ISSUES – CCP RECOGNITION 32 Derivatives Trades Cross Borders Source: www.united.com 33 Financial Stability Board Area Standard Issuing Body Macroeconomic Policy and Data Transparency Monetary and financial policy transparency Fiscal policy transparency Data dissemination Code of Good Practices on Transparency in Monetary and Financial Policies Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency Special Data Dissemination Standard/ General Data Dissemination System IMF IMF IMF Financial Regulation and Supervision Banking supervision Securities regulation Insurance supervision Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation Insurance Core Principles BCBS IOSCO IAIS Institutional and Market Infrastructure Crisis resolution and deposit insurance Insolvency Corporate governance Accounting and Auditing Payment, clearing and settlement Market integrity Core Principles for Effective Deposit Insurance Systems BCBS/IADI Insolvency and Creditor Rights Principles of Corporate Governance International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) International Standards on Auditing (ISA) Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures World Bank OECD IASB IAASB CPMI (CPSS)/ IOSCO FATF FATF Recommendations on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation 34 Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMI) • • • • The Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (f/k/a the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems) (“CPMI”) of the Bank for International Settlements and the Technical Committee of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (“IOSCO”) developed the PFMI. The PFMI provide new international standards for financial market infrastructures (FMIs), including: – payment systems (PSs) that are systemically important; Margin – central securities depositories (CSDs); – securities settlement systems (SSSs); – central counterparties (CCPs); and Operational Liquidity Risk Risk – trade repositories (TRs). The PFMI also set forth five responsibilities of central banks, market regulators and other relevant authorities for FMIs as they relate to the regulation, supervision and oversight of FMIs, including, cooperation with other authorities. There are 24 Principles for FMIs, including those listed to the right. Settlement Credit Risk Default Rules 35 PFMIs and QCCP Status • A qualifying central counterparty (QCCP) is an entity that is licensed to operate as a CCP (including a license granted by way of confirming an exemption), and is permitted by the appropriate regulator/overseer to operate as such with respect to the products offered. – This is subject to the provision that the CCP is based and prudentially supervised in a jurisdiction where the relevant regulator/overseer has established, and publicly indicated that it applies to the CCP on an ongoing basis, domestic rules and regulations that are consistent with the PFMIs. • In addition, for a CCP to be considered a QCCP, the CCP must make available or calculate required data for the purposes of calculating the capital requirements for default fund exposures. 36 Basel and the QCCPs • In December 2010 and January 2011, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) published wide ranging changes, in line with G20 decisions, to global standards on capital and liquidity requirements. While these standards are not binding, they are largely adhered to in the formulation of final rules in each jurisdiction. • The aim of these standards is to promote a more resilient banking system, with an improved ability for banks to absorb shocks and a reduced level of systemic risk in the banking sector as a whole. • The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s bank capital regime creates financial incentives for banks to clear their financial derivatives through QCCPs, which are generally defined as clearinghouses that are subject to rules consistent with the PFMIs. 37 CFTC - Exempt DCOs • • • • • Any clearinghouse that clears swaps directly for U.S. clearing members or indirectly for the U.S. customers of U.S. and non-U.S. clearing members must register with the CFTC as a DCO or obtain an exemption. The CFTC has statutory authority to exempt clearinghouses from DCO registration if the CFTC determines that the clearinghouse is subject to “comparable, comprehensive supervision and regulation” by the clearinghouse’s home country regulator. The CFTC has not yet exempted any swaps clearinghouses from registration or proposed a way for a clearinghouse to apply for an exemption. Recently, Staff of the CFTC’s Division of Clearing and Risk (DCR), said that the draft of the proposed DCO rulemaking provides that in order for a clearinghouse to be eligible for an exemption, it must, among other things, observe the PFMIs and be organized and in good standing in a jurisdiction where the regulator applies legal requirements consistent with the PFMIs. However, the Staff of DCR said it intends to recommend that exempt DCOs be prohibited from clearing for U.S. customers. This is because certain aspects of the CFTC’s Part 22 requirements regarding the protection of client collateral for swaps conflicts with the regulatory schemes guiding non-U.S. clearinghouses. 38 CFTC - Foreign DCOs • • • LCH.Clearnet SA (Designated as a DCO on 12/17/13) – LCH. Clearnet SA is regulated as a clearing house by the Autorité des Marchés Financiers (“AMF”) and as a credit institution by the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel (“ACP”) – LCH.Clearnet SA’s DCO registration contains a restriction, required by the CFTC, to “ring-fence” swaps customer collateral, such that it can be treated as separate from the general estate of the DCO and cannot be commingled with other accounts. In other words, the CFTC requires foreign DCOs to assure that US Bankruptcy law will govern a default. Singapore Exchange Derivatives Clearing Limited (SGX-DC) (Designated as a DCO on 12/27/13) – SGX-DC’s DCO registration contains similar restrictions. Comder (planned) – Clearinghouse located in Chile which clears NDFs and IRS vanilla. – CCP design based on BIS-IOSCO recommendation and other CCPs best practices. 39 Collateral Conflict ≠ Bankruptcy Law • • • • THE ISSUE: There is a conflict between European Union (EMIR) and U.S. rules (Dodd-Frank/CFTC) regarding the protection of client collateral for swaps. Swaps Collateral Model US Europe LSOC (US law) Yes No Omnibus Model No Yes Individual Segregation No Yes Swaps Trades executed on U.S. exchanges are required to clear through CFTC-registered FCMs, which are subject to LSOC. The CFTC could provide an exemption from LSOC for the EMIRrelated clearing models, but this would be unprecedented. The CFTC requires foreign clearinghouses to register as a DCO with the CFTC, with CFTC-registered FCMs as clearing members. 40 QCCP Recognition 20% 2% ≠ QCCP • The “Collateral Conflict” has resulted in the EU delaying recognition of the U.S. CCPs in the EU. • Under Europe’s Basel III requirements, banks have until December 15th to treat non-EU clearers as qualifying CCPs or “QCCPs.” • The QCCP designation allows the lowest risk weight of 2% for a bank’s clearing exposures. • After December 15th, if a CCP is not a QCCP, then the riskweights increase up to at least 20%, which means the banks would need to dramatically increase capital. • This is an issue because CFTC-regulated clearinghouses are not yet recognized in the EU as equivalent - they’re not QCCPs. 41 QCCP Recognition • • • • The CFTC believes DCOs registered with the CFTC should be recognized because CFTC regulated clearinghouses meet the international standards. However, the EU has said in order for them to recognize US DCOs, changes are needed in the CFTC’s treatment of clearinghouses that are located in Europe, but are also registered with the U.S. The EC cites EMIR as the reason for such as a decision because EMIR requires a reciprocal regime of a foreign entity for authorizing European and other third-country clearers in order to grant an equivalency determination. According to Chairman Massad, the CFTC and Europeans are working to have DCOs recognized overseas. Chairman Massad recently stated that the CFTC is looking at whether the CFTC can further harmonize its rules. As a result of this work, the European Commission postponed the imposition of higher capital charges on European banks participating in CFTC registered DCOs. The CFTC has not yet issued its rule on exempt DCOs, but the CFTC indicated that those rules would prohibit foreign clearinghouses from accepting US clients. As noted above, the rules currently only allow a nonUS CCP that is fully registered as a DCO to clear for US clients. 42 QCCP Recognition • On October 30, 2014, the EC announced its first “equivalence” decisions for the regulatory regimes of CCPs in Australia, Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore: Globally agreed reforms of derivatives markets – like all financial services reforms – will only work in international markets if regulators and supervisors rely on each other. Today's decisions show that the EU is willing to defer to the regulatory frameworks of third countries, if they meet the same objectives as EU rules. We have been working in parallel on assessing twelve additional jurisdictions and finalising those assessments is a top priority. This includes the United States: we are in close and continued dialogue with our colleagues at both the SEC and CFTC as we develop our assessments of their respective regimes and discuss their approaches to deference. Equivalence Equivalence Pending 43 KEY ATTORNEY PROFILES ATTORNEY PROFILE STEPHEN M. HUMENIK Of Counsel shumenik@cov.com Covington & Burling LLP 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20004-2401 Tel: 202.662.5803 Stephen Humenik leads the firm’s futures and derivatives practice. He has extensive experience on regulatory and enforcement matters involving the CFTC and the derivatives and commodities markets. Specifically, Mr. Humenik advises clients on regulatory and policy matters relating to the registration and compliance obligations of the Dodd-Frank Act and represents clients in CFTC enforcement investigations and proceedings. Prior to joining Covington, Mr. Humenik was general counsel and chief regulatory officer of Eris Exchange, LLC, an interest rate swap derivatives market, where he oversaw the legal and regulatory affairs of the exchange, including the exchange’s designation as a contract market and ongoing compliance with CFTC regulations. Mr. Humenik previously served as Special Counsel and Policy Advisor to Commissioner Scott O’Malia where he assisted on rulemaking, enforcement and legislative matters. Mr. Humenik began his career at the CFTC and primarily served as Senior Trial Attorney for the CFTC’s Division of Enforcement where he investigated and litigated complex fraud and market manipulation cases, specifically those involving energy and financial derivatives and physical commodities. Mr. Humenik also practiced in the SEC enforcement group of a law firm in Washington, DC. 45 ATTORNEY PROFILE CHARLOTTE HILL Partner chill@cov.com Covington & Burling LLP 265 Strand London WC2R 1BH Tel: 44.(0)20.7067.2190 Charlotte Hill is a financial services and regulation partner in the London office. She specialises in advising financial institutions on regulatory and commercial matters. Ms. Hill has had considerable industry experience during her career, having worked at the regulator, IMRO (a predecessor regulator of the FCA) in the enforcement division and subsequently, was Director of Legal at Threadneedle Investments. This industry experience is invaluable in providing clients with truly commercially focused advice. Ms. Hill's clients range from very large, multi-national conglomerates to specialist boutiques. Ms. Hill has been recognised as a Leading Individual by Chambers UK since 2010, who note “her in-depth knowledge of the FSA” and “professional, responsive” approach, as well as Legal 500 UK (20102013). Ms. Hill regularly publishes articles on regulatory topics in a range of industry publications and speaks at both external conferences and seminars and in-house client training events. 46 ATTORNEY PROFILE BRUCE C. BENNETT Partner bennett@cov.com Covington & Burling LLP The New York Times Building 620 Eighth Avenue New York, NY 10018-1405 Tel: 212.841.1060 Bruce Bennett is head of the financial services institution group at Covington, resident in the New York office. Mr. Bennett's practice focuses on domestic and international capital markets transactions, including equity, equity-linked and fixed income (high yield and investment grade) offerings. He also regularly represents participants in structuring and executing a wide range of derivatives transactions, as well as with respect to related ISDA documentation. In addition to his transactional practice, Mr. Bennett advises clients on regulatory and policy matters affecting the capital markets, with particular focus on the Dodd-Frank Act and related regulations. He regularly represents clients on interpretive issues before the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and other regulatory agencies. Mr. Bennett is also a frequent speaker at corporate and securities law seminars and regularly publishes in these fields. 47 ATTORNEY PROFILE JOHN DUGAN Partner jdugan@cov.com Covington & Burling LLP 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20004-2401 Tel: 202.662.5051 John Dugan formerly Comptroller of the Currency from 2005-10, is a partner in the firm’s Washington, DC office and chairs the firm’s Financial Institutions Group. He advises clients on a range of legal matters affected by significantly increased regulatory requirements resulting from the financial crisis, including implementation of the Dodd-Frank Act; financial institution mergers, acquisitions, and investments; litigation and enforcement issues; international financial regulation; and legislative and government relations issues. As Comptroller, Mr. Dugan headed the agency that supervises over 1,500 national banks and federal branches of foreign banks, which together hold nearly two-thirds of the assets of the US commercial banking system. He also served on the Board of Directors of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. During his five-year term, Mr. Dugan led the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) through the financial crisis and ensuing recession that resulted in extraordinary regulatory and supervisory actions for national banks of all sizes, including government assistance provided under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP); resolutions of large, midsize, and community banks; and the successful implementation of regulatory “stress tests.” Before serving as Comptroller, Mr. Dugan was a partner in the firm, specializing in financial institution regulatory matters from 1993-2005. He had previously served at the U.S. Department of the Treasury from 1989 to 1993, where he was appointed Assistant Secretary for Domestic Finance and had extensive responsibility for policy initiatives involving banks and financial institutions, including the savings and loan cleanup, Glass-Steagall and banking reform, and regulation of government-sponsored enterprises. 48