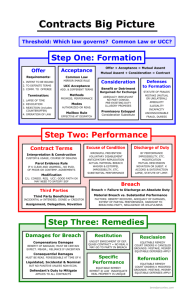

Acceptance

advertisement