reforming civil procedure rules to enhance access to justice in nigeria

advertisement

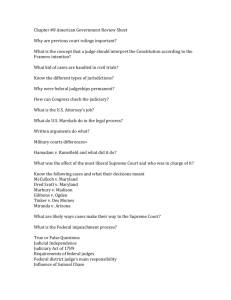

REFORMING CIVIL PROCEDURE RULES TO ENHANCE ACCESS TO JUSTICE IN NIGERIA: THE LAGOS STATE EXPERIENCES INTRODUCTION The concept of a fair hearing has been the heart of social justice both in our customary law systems and in our adopted common law tradition. As a result, court systems and enforcement machineries have, from time immemorial, been standard paraphernalia of organised societies in Nigeria. Indeed, access to the justice system can be considered the hallmark of civilisation. The 1999 constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria continues the tradition by establishing a rich court system, featuring Customary and Sharia Courts alongside Magistrates and High Courts. The pyramid ranges up through the appellate courts to the Supreme Court. The same constitution also establishes a Police Force to compliment the in - built enforcement structures of the court system. To guarantee access to this justice system, section 36 (1) of the Constitution provides that; “In the determination of his civil rights and obligations, including any question or determination by or against any government or authority, a person shall be entitled to a fair hearing within a reasonable time by a court or 1 other tribunal established by law and constituted in such a manner as to secure its independence and impartiality”. This provision shows clearly an intention to guarantee access to justice not only to the complainant or plaintiff but also to the respondent. However, section 36 (1) is more often invoked by respondents who were not offered any real opportunity to be heard before an adverse determination of their rights. Hardly would you hear a complaint from the Plaintiff who has successfully gained access to the court system in an attempt to vindicate his rights but who is unable to get his case determined. It really does appear that while he is actively taking advantage of the justice system, he should have nothing to complain about. This has led to a rather one – side view of access to justice; focusing on those that are deprived entry and virtually ignoring those that did enter but are locked in an endless search for justice. However, a closer look at section 36 (1) reveals clearly that the objective is not a guarantee access to the courts per se. Rather, it is to guarantee access to justice - a fair hearing within a reasonable time by an impartial judge. The fact that anybody could issue a writ of summons at anytime and at little cost was therefore a 2 misleading ‘achievement’. The real question should have been “how many people got justice or had their cases fairly determined within a reasonable time?” As of 1999 when the military era came to an end, the answer was quite appalling. But up till now, it seemed that while we all agreed that justice delayed was justice denied, we had regarded that time worn phrase more as a normative or an idealistic one, the realisation of which was not a priority issue. It is not surprising therefore that while everybody kept busy going in and coming out of courtrooms, the problem of “justice delayed” climbed to a dizzying height without attracting much solution. IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM In Lagos State, we have since made a multi-layered but sustained effort to identify the real problems and device workable solutions. This began in 1999, even before the current administration was sworn in. Immediately after the 1999 elections, I was privileged to be part of a small group of lawyers appointed by the then Governor-elect of Lagos State, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, to develop a justice policy for Lagos State. The group eventually produced a blueprint that became the main guide of Lagos justice reform project. The blueprint made an important philosophical conclusion – namely; that the justice system must be capable of protecting Key 3 developmental policies, which include the protection of fundamental rights, law enforcement, and social justice. A closer scrutiny of the system revealed that the interminable delays suffered by litigants were its most virulent problem. Like an unattended cancer, it tended to grow bigger and bigger. Signs of congestion, especially in the High Courts had began to show as far back as the mid – eighties but with persistent neglect by the 1990s, a situation had arisen which assured that many of the cases filed in the late 1990s did not stand a reasonable chance of being concluded within a decade, especially where there were interlocutory appeals. As of May 2000, pending cases at the Lagos High Court were in order of 40,000. To give a sense of the workload in Lagos State compared with another busy jurisdiction - Rivers State. The table below shows: YEAR COURT FRESH CASES FILED PENDING CASES 1999 Lagos 10,226 20, 169 Rivers 2,409 8, 398 2000 Lagos 9,969 23,197 Rivers 3,399 10,669 4 A study conducted on the duration of trials in the Lagos High Court, indicated the following results; TYPE OF CASE Land Matters Personal Matters Commercial Cases Family Cases TRIAL TIME 7-8 years 3-4 years 3-5 years 2-5 years Going by this Table, the overall average for cases was 4.25 years. These figures of course assume that there would be no interlocutory appeals which could drag the process on for an additional 50- 75% of the average expected duration. Prior to the drafting of the new civil procedure rules, another study was conducted by the Ministry of Justice in August, 2001 which showed that it took an average of 5.9 years for a contested case to move from filing to judgement. Indeed the administrative process of instituting a case i.e., from point of filing to assignment to court, could take as long as 6 weeks. As may be expected, other random studies show that few lawyers who practiced regularly in the Lagos High Court were able to conclude 10 contested cases in 10 years. UNDERLYING CAUSES 5 Several factors accounted for this problem. First, there was a shortage of judicial officers. In May 2000, the Lagos High Court was down to about 30 Judges - and by December 2001, the number had further reduced to 26, due mainly to retirement of the older judges. At an average trial time of 5.9 years it was clear that the vast majority of cases would not be concluded even in the new century especially considering that anywhere between 10,000 to 12,000 new cases were expected in the year 2002 and incrementally from year to year. In effect, our studies showed that to make a significant impact on the pending and current cases within a 5 year period, we needed to have not less than 100 judges working a full 9:00am to 3:00pm daily. We also found that technology could assist in a major way. Our trial run of digital recorders and transcribers in the courtroom indicated that they had the capability of cutting trial time by half. Therefore, we concluded that it was possible to make the desired impact with about 55 judges who had the necessary equipment and were well remunerated, with a decent housing, transportation and other encouragement by way of a carefully planned benefit scheme. This also called for additional courtrooms and upgraded equipment. 6 The last major culprit, as we found out, was the civil procedure rules of the High Court. As of 1997, when the earliest and most authoritative surveys of the legal practice and the trial procedure was conducted by a joint effort of the Lagos Judiciary, Hurilaws, (a justice sector NGO) and the Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, one of the major results was that the civil procedure rules required a radical makeover of the problem of trial delays was to be dealt with. In 2000, we took up the issue at our first Stakeholders Summit on Administration of Justice in the 21st Century. By the time of the 2nd summit, it had become the single issue for consideration. SUGGESTIONS FOR REFORM In composing the new rules, the Lagos Rules Committee considered the memoranda submitted by various authors, jurists and legal practitioners as well as the final communiqué of the 2nd summit which dealt exclusively with civil procedure. The old High Court Rules still formed the basic working document, but the committee had, in addition the two models which featured for review at the 2nd summit. It also had the Woolf’s Report on which the new English Rules were based. MAJOR CHANGES EFFECTED BY THE NEW RULES 7 The new rules were passed into law and finally into effect in June 2004. As stated in Order 1 Rule 2, application of the rules “shall be directed towards the achievement of just, efficient and speedy dispensation of justice”. The new rules adopt the concept of case management, front loading and pre-trial conferencing, all of which are intended to relieve congestion in the Courts by reducing the number of cases that actually go to trial. It is significant to note that many of these concepts were adopted in the 1999 review of the Civil Procedure Rules of England and Wales upon the recommendation of the Woolf’s committee. To the same end, many time wasting procedure or obsolete rules were abandoned and judges were given a firmer control over proceedings in the Courts. SERVICES OF PROCESSES All studies indicated that the starting point of delays in the judicial process was at the Sherrif’s Department. For a long time, delay in the service of court processes had been one major suppressant of judicial activity. This was due mainly to corruption and inefficiency of the Sherrif’s Department. By virtue of the new Order 7 Rule 1, any law firm, Courier Company, or any other person appointed by the Chief Judge can now serve originating processes. This is to supplement the usual crop of process servers, which includes the Sherriff, Deputy 8 Sherrif, Bailiff, Special Marshal or other officers of the court. FRONT LOADING We also found that the old method of issuing a writ to commence proceedings, filing pleadings at a later date and revealing evidence only as trial progresses, allow many unserious litigants to clog the system. It also made it impossible for the judge to apprehend the issues in dispute or attempt a settlement early enough. Under the new rules, both claimant and defendant are now expected to reveal their entire case before trial. For example, all civil proceedings commenced by writ of summons must be accompanied by a statement of claim, list of witnesses to be called at the trial, written statements on oath of the witnesses and copies of every document to be relied upon at the trial. Where a claimant fails to comply, his originating process will not be accepted for filing by the registry (Order 3 Rule 2). Similarly, under Rule 8, an originating summons must be accompanied by an affidavit setting out the facts relied upon, all exhibits to be relied upon, and a written address in support of the application In the same vein, the defendant who is served with an originating process is expected to file a statement of defence accompanied by copies of documentary 9 evidence, list of witnesses and their written statements on oath (Order 17 Rule 1). This he must do within 21 days of service on him of the originating processes. In cases commenced by originating summons, the defendant must file a counter affidavit together with all the exhibits he wants to rely upon and a written address within 21 days within the service of originating summons (Order 17 Rule 17) ‘Frontloading’ enables the trial judge to identify the points in controversy between the parties as soon as the pleadings close, schedule trial to refer the parties to alternative dispute resolution methods as may be appropriate. Also, it makes it possible for parties to settle all preliminary matters and most issues of admissibility of evidence before actual trial of the case. As was expected, this has the effect of drastically reducing the number of cases that come to court as well as the amount of time it takes to dispose of them. Pre-trial conferencing The old summons for Direction is to be replaced with pre-trial conferencing. Within 14 days of close of pleadings, the claimant is required to apply for Pre—trial Conferencing Notice (Form 17). This notice is issued along with Pre-trial Information Sheet (Form 18). Specifically, the pre-trial conference is for disposal of those matters which that can be dealt with on 10 interlocutory application. It also enables the judge to give such directions as to future course of action as appear best adapted to secure its just, expeditious and economical disposal. In appropriate cases, the judge uses the opportunity to promote amicable settlement or adoption of alternative dispute resolution. If the claimant does not make application for pre-trial notice, the defendant has an option of doing so or applying for an order to dismiss the action (see generally Order 25) Scheduling Order At the pre-trial conference, the Judge enters a scheduling order regarding things to do in furtherance of the case, e.g., joinder of other parties to the action; amendment of pleadings or other processes, filing of motions; further pre trial conferences; or any other step that appears necessary in the circumstances of the case. The pre-trial judge also considers and takes appropriate action on the following: (a) formulation and settlement of issues; (b) amendments and further and better particulars; (c) the admissions of facts, and other evidence by consent of the parties; (d) control and scheduling of discoveries; inspection and production of documents; 11 (e) narrowing the field of dispute between expert witnesses, by requesting their participation at the pre-trial conference or in any other manner; (f) eliciting preliminary objections on point of law; (g) hearing and determination of non-contentious motions; giving orders or directions for separate trials of a claim, counterclaim, set-off, cross-claim or third party claim or of any particular issue in the case; (h) settlement of issues, inquiries and accounts under Order 27; (i)securing statement of special case of law or facts under Order 28; (j) determining the form and substance of the pretrial order; (k) such other matters as may facilitate the just and speedy disposal of the action. Deadline for completion of Pre-trial Pre-trial conference in any particular case must be completed within three months of close of pleadings, and the parties and their legal practitioners are expressly enjoined to co-operate with the judge in working with this time-table. If the pre- trial conference does not end within three months period, the case has to be referred to the Chief Judge for further directions. Thus only Chief Judge can extend the time allowed for pre-trials. It is expected that this time limit and 12 supervisory role of the Chief Judge would prevent the pre trial conference from becoming another long drawn out procedure. As far as practicable, pre-trial conference are to be held from day to day or adjourned only for purposes of compliance with pre-trial conference orders. Upon completion of pre- trials, the pre- trial judge issues a Report, which serves as a guide to subsequent course of the proceedings unless modified by the trial judge. Obligation to Participate in Good Faith If the claimant or his legal practitioner fails to attend the pre-trial conference or obey a scheduling order, or is substantially unprepared in good faith, the judge will simply dismiss the claim. Where the default is that of the defendant, the judge may enter final judgement against him. However, any judgement given under this rule may be set aside upon an application made within seven days of the judgement or such other period as the Pre-trial judge may allow, not exceeding the pretrial conference period. Such application shall be accompanied by an undertaking to participate effectively in the pre-trial conference. Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) 13 There is no doubt that the way forward for a justice system committed to enlarging access to and ensuring effective and timely delivery of justice is the use of ADR. Year by year we realize with greater consternation that the courts simply cannot cope alone with the number of pending cases, and that several cases need not come before the courts, they are better suited to ADR. As may be seen from the stated objectives of the pretrial conference, the new rules give recognition to the need for many cases to be referred for ADR. To facilitate this process, the High Court of Lagos State has a Multi-door Courthouse, a facility that provides a number of ADR options to litigants. This concept has so far been a great success. The number of referrals to mediation, arbitration and conciliation has grown incrementally every year- and several cases, some of which had gone on in the courts for years, have been resolved using ADR methods. Interrogatories and Inspection The old rules on discovery and inspection were hardly ever used, so they have been restructured. Now the claimant or defendant in any proceeding has the right to deliver interrogatories in writing for the examination of the opposite party and such interrogatories must be delivered within seven days of close of pleadings. Indeed, they form part of the agenda of pre-trial 14 conference. Interrogatories are also required to be answered by affidavit filed within seven days, or within such other time as the judge may allow. If any person interrogated refuse to answer or answers insufficiently, the pre trial judge shall on application issue an order requiring him to answer or to answer further as the case may be (see Order 26 particularly rules 1, 5, and 7). Under the current dispensation, inspection is expected to take place during pre trial conference. Amendment and adjournments The review process also affects the old rule on amendments and adjournments. These two are reputed to be the major causes of delay in civil litigation. Under the old rules, adjournments were granted almost as a matter of course and a party was allowed to amend his pleading at any time before judgement. The position has now changed. A party may amend his originating process and pleadings at any time and as many times as he wishes before the pre- trial conference and during the conference, but he cannot amend more than twice during the actual trial. In fact, it is envisaged that by the time parties are through with the pre trial and the real issues in controversy have been agreed and set down for hearing, there will be little or no need to amend the pleadings. 15 In cases where any originating process or pleading is to be amended, the application must be accompanied with a list of any additional witnesses to be called, their written statements on oath and copies of any statements on oath and copies of any document to be relied upon consequent on such amendment. This is in line with the front- loading concept described earlier. The requirement of leave to amend is however dispensed with to save time. The application to amend is brought directly before a judge and may be allowed upon such terms as to costs or otherwise as may be just (see order 24 Rule 1 & 3). Attempts are also made in the new rules to curtail the number of adjournments that a court would allow. Apart the award of realistic costs to be paid by the defaulting party, the rules provide that hearing of any motion or application may from time to time be adjourned provided that application for adjournment at the request of a party shall not be made more than twice (see order 39 Rule 7). Presumably, any party who is unable to move his motion or application after seeking two adjournments would be deemed to have abandoned it. The Respondent who is likewise tardy would also be deemed to consent to the application, which would then be granted, except it is by itself baseless of fundamental defective. 16 Use of written Addresses Though hitherto unknown to any law or rules regulating trial at the High Court level, the practice of submitting written address was fast gaining ground, especially in civil proceedings. This was because of its inherent advantages as a time saving devise, which also provided accurate records of argument proffered by the parties. Now, by the virtue of the new Order 31, written addresses are required to back up all application and final addresses in the High Court of Lagos state. The address must be printed on white opaque A4 size paper and set out in paragraphs numbered serially and should contain: I. The claim or application on which the address is based; II. A brief statement of the facts with reference to the exhibit attached to the application or tendered at the trial; III. The issue arising from the evidence; IV. A succinct statement of argument on each issue incorporating the purpose of the authorities referred to together with full citation of each such authority. The address must be concluded with a numbered summary of the points raised, the party’s prayer, and a list of all authorities referred to. Where any unreported 17 judgment is relied upon the Certified True Copy has to be submitted along with the written address. Aside from saving trial time, these requirements also ensure that lawyers pay closer attention to the formulation and expression of their arguments. This should, on the whole, raise the standard of legal practice in our courts. By virtue of order 31, oral arguments of not more than twenty minutes are allowed for each party to emphasize and clarify his written address. This is expected to allay the fear of some commentators who were of the view that institutionalization of written addresses would stifle advocacy among lawyers. Penalties and Costs Another cause of delay under the old regime was the ultra low cost of obtaining adjournment and taking the court through frivolous detours. Under the new rules penalties are stricter. Also, costs to be awarded are expected to be a realistic representation of the loss suffered by the innocent party. These are all intended to speed up trial, mainly by discouraging frivolous application for adjournment. For instance, Order 44 Rule 4 provides that the judge may, as often as he deems fit, and either before or after the expiration of the time of appointed by the rules or by any judgment or order of the court, extended of adjourn the time for doing any 18 act or taking any proceedings, provided that any party who defaults in performing an act within the time authorized by the judge or under the rules, Shall pay to the court the additional fee of N200.00 for each day of such defaults at the time of filling his application for extension of time. Also, a defendant who enters appearance after the time prescribed in the originating process for doing so is required to pay an additional fee of N200 for each day of defaults (Order 9 Rule 5). Furthermore, Order 24 Rule 4 provides that if a party who has obtained an order to amend does not amend accordingly within the time limited for that purpose by the order, or if no time is thereby limited, then within 7 days from the date of the order, such party shall pay an additional fee of 200.00(two hundred naira) for each day of defaults. The upward review of penalties under the news rules is perhaps most apparent in the section on probate. For instance, the liability imposed an executor who neglects to apply for within 3 months of the testator’s death has been raised from 100 to 50,000.00. A similar penalty of N50,000.00 is imposed on an unauthorized person who intermeddles with an estate (see Order 53 Rules 3 and 4). 19 Costs payable as they arise Under these Rules, when cost is ordered, it immediately becomes payable, and must be paid within 7 days of the order. Otherwise, the defaulting party or his legal practitioner may be denied further audience in the proceedings. As stipulated in Order 49 Rule 8, where the judge orders costs to be paid or security to be given for costs by any party, the judge may order all proceedings by or on behalf of that party to be stayed until the costs are paid or security given accordingly. However, such an order shall not supersede the use of any other lawful method of enforcing payment. Personal liability of legal practitioner for cost One of the arguments which sustained the low rate of costs awarded in the past was that a litigant should not be punished for the negligence of his counsel. Under the new rules, a legal practitioner may now be held personally liable for costs arising from his own negligence. Where in any proceedings costs are incurred improperly or without reasonable cause or are wasted by undue delay or by any other misconduct default, the judge may make an order of personal liability or indemnity against any legal practitioner whom he 20 considers to be responsible (whether personally or through a servant or agent)(Order 49 Rule 13) Costs may be ordered in the course of trail or taxed in separated proceedings upon the termination of the case. In the latter case, any party to the taxation proceedings who is dissatisfied with the allowance or disallowance (in whole or in part) of any item by a taxing officer or with the amount allowed by a taxing officer in respect of any item, may apply to the judge for an order to review the taxation as to that item (Order 49 Rule 26). Transition and Training To ensure a successful transition to the new rules regime, the Lagos State Ministry of Justice collaborated with the State Judiciary to organize a series of training programmes both for the judges and practitioner. The first Judges’ Workshop on the new rules created the forum for members of the Rules Committee to explain the intendment of the changes and to brainstorm with the judges on the likely problem areas. This was followed by another seminar led by Fidelis Oditah, QC, SAN, who had practiced extensively, with similar rules in England. The problems identified at two meetings formed the basis of another seminar, which featured Judge Paul Collins, CBE and Judge Keith Hollis both of the English Bench, and Oba Nsugbe, QC who brought the 21 perspectives of another English Barrister. The objective of this third meeting was to enable judges of the High Court of Lagos State learn from the experiences of the English Judges, both of whom were closely involved in training programmes organised by the Judicial Studies Board of England (JSB) before the implementation of new civil procedure rules (Woolf Reform) in that country. Three sets of such Seminars have also been held for legal practitioners and the suggestions that emanated from all these seminars informed the first set of amendments and re-enactment of the new rules in 2004. In spite of these, we still anticipate a constantly evolving set of rules. The Rules Committee is therefore kept standing and charged with the task of keeping in view possible areas of improvement. They are also to submit draft Practice Directions to the Chief Judge from time to time, which can then be issued to smoothen those minor creases that do not justify an amendment to the Law Complementary Activities To further enhance the speed of access to justice, the Lagos state Government is currently implementing a court Automated Information System which will computerize existing manual processes and create a 22 database of all cases pending before each judges and their current status until delivery of judgment and execution. The database will enable administrative judges to track cases and establish checkpoints for queries if a case is unduly prolonged relative to set performance standards. Intranet and Internet facilities are available on this system and counsel and litigants should, be able to access the cause list and other case information on the internet from their own offices. The automation process, which is assisted by the U.K. Directorate for International Development, is practically concluded. The first phase should go live. Also, we installed digital recorders and transcribers for all the High Court in Lagos State. As noted earlier, this on its own has an established potential of reducing trial time by half. Conclusion This overview of the new rules of civil procedure shows clearly that a lot of changes have been introduced to practices in the High court of Lagos state. Much work will now be done by Lawyers in Chambers ever before they approach the courts. In the process of gathering the evidence and preparing pleadings and arguments, lawyers to many would –be claimants will definitely come to realise the futility of the proposed court action. 23 Similarly, a defendant who gets a total picture of the case along with witness` dispositions and documentary evidence is quite unlikely to put up a defence, unless he is sure of his own position. With all the materials exchanged by the parties and before the judge, it is easier to apprehend the matters in dispute and to attempt settlement by ADR. The Judge will have to firm control of proceedings as he has been empowered to penalize frivolous application. Inevitably, all these will result in a rapid decongestion of the courts. Only those with serious cases will have access to justice and real justice, which can only come from a fair resolution of submitted disputes, will be much closer to hand. This is of course not presented as perfected. In fact, we do not see it as such. That is why we have machinery in place for a constant review and reform of the rules. We are also doing our best to ensure that interactions such as this occur as frequently as possible. The problems of facilitating quick access to justice is a constantly evolving one and it takes the watchful attention of all stakeholders – litigant, lawyers and judges – to keep it in check. Thank you 24