The Hon. Madam Justice Patricia Hennessy

advertisement

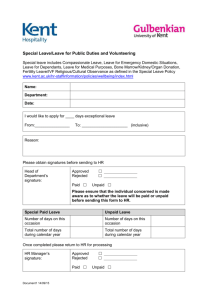

Plenary Session 8: Women, Work and Health The Honourable Madam Justice Hennessy Superior Court of Justice of Ontario, Canada Linking Work and Health Through the Law • • • • • • Equal treatment – Human Rights Safety in the work place Minimum wage Income replacement Pregnancy and parental leave Pension Why do we work? The Court recognizes the primary place of work in our lives. “Work is one of the most fundamental aspects in a person’s life, providing the individual with a means of financial support and, as importantly, a contributory role in society. A person’s employment is an essential component of his or her sense of identity, self-worth and emotional well-being.” Dickson C.J., Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta.), [1987] 1 S.C.R. 313, at p. 368. Canadian Context - Paid Workforce • The work force has greatly changed in Canada in the last 40 years. In 1976, women comprised 37.1% of employed Canadians. In 2009, they comprised 47.9%. • Certain groups of women in Canada are more vulnerable than others • The female Aboriginal unemployment rate in 2009, 12.7% was nearly twice that of non-Aboriginal women, 6.9% Vincent Ferrao, Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report (Paid work) (Ottawa: Minister of Industry, 2010). Unpaid work The hours in a day of paid and unpaid work completed by men and women in Canada 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 Paid work 2.5 Unpaid work 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 Men Women Canadians living in poverty 40 % living in poverty (2000) 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 All people All women Aboriginal living in women Canada Visible miority women Women Single with parent disabilities mothers www.canadianwomen.org: The facts about women and poverty Single senior women Recognition of the value of unpaid work • Statutes in the family law context: • Division of property • Spousal support • Compensation for unpaid work in tort law Family Law: Division of Property Recognition of Unpaid Work It must be recognized that when [women work exclusively in the home], women forgo outside employment to provide domestic services and child care. The granting of relief in the form of a personal judgment or a property interest to the provider of domestic services should adequately reflect the fact that the income earning capacity and the ability to acquire assets by one party has been enhanced by the unpaid domestic services of the other. Peter v. Beblow, [1993] 1 S.C.R. 980, at p. 1015. Family Law: Division of Property Recognition of Unpaid Work For many domestic relationships, the couple’s venture may only sensibly be viewed as a joint one, making it highly artificial in theory and extremely difficult in practice to do a detailed accounting of the contributions made and benefits received on a fee-for services basis. … [T]he legal consequences of the breakdown of a domestic relationship should reflect realistically the way people live their lives. It should not impose on them the need to engage in an artificial balance sheet approach which does not reflect the true nature of their relationship. Kerr v. Baranow, 2011 SCC 10, at para. 69. Family Law: Spousal Support Recognition of Contribution of Unpaid Work Factors to determine the amount and duration of spousal support include: • a contribution to the realization of the respondent’s career potential; • any housekeeping, child care or other domestic service performed for the family, as if the spouse were devoting the time spent in performing that service in remunerative employment and were contributing the earnings to the family’s support, • the effect on the spouse’s earnings and career development of the responsibility of caring for a child Family Law Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.3, s. 33(9). Compensation in Tort Law Recognition of Unpaid Work [H]ousekeeping and other spousal services have economic value for which a claim by an injured party will lie even where those services are replaced gratuitously from within the family. Kroeker v. Jansen , [1995] B.C.J. No. 724, at para. 9. Work Place Protections • • • • • • • Discrimination Vulnerable workers Safe workplaces Domestic violence Harassment Pregnancy and parental leaves Sex workers Human rights Law Provides for Equal Treatment • Every person has a right to equal treatment with respect to employment without discrimination because of race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, sex, sexual orientation, age, record of offences, marital status, family status or disability. Human Rights Code, R.S.O. 1990, c, H.19, s. 5(1). Equal pay for equal work No employer shall pay an employee of one sex at a rate of pay less than the rate paid to an employee of the other sex when, a) they perform substantially the same kind of work in the same establishment; b) their performance requires substantially the same skill, effort and responsibility; and c) their work is performed under similar working conditions. Employment Standards Act, 2000, S.O. 2000, c. 41, s. 42. Minimum age protects vulnerable workers • Must be 14 years old to work • A young person between the ages of 14 and 17 inclusively cannot work during school hours • Certain trades and sectors can only hire adolescents older than 14 (ex. Construction: 16 years; Underground Mines: 18 years) Industrial Establishments, R.R.O 1990, Reg. 851, s. 4(1). Occupational Health and Safety Provincial laws impose general duties on employers, such as: • Take all reasonable precautions to protect the health and safety of workers • Ensure that equipment, materials and protective equipment are maintained in good condition • Provide information, instruction and supervision to protect worker health and safety Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1. Employer’s duty regarding domestic violence Where and employer knows or ought reasonably to know that domestic violence will likely expose a worker to injury in the workplace, the employer has a duty to take reasonable precautions for the protection of the worker. Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1, s. 32.0.4. Assented December 2009. Harassment free workplace Every employee has a right to freedom from harassment in the workplace because of sex, marital status, family status, etc. Human Rights Code, R.S.O. 1990, c, H.19, ss. 5(2), 7(2). Income replacement during pregnancy & parental leave • Pregnancy leave: • 15 weeks of limited income replacement • Parental leave: • 35 weeks of limited income replacement which can be taken by either parent or shared by both parent Employment Insurance Act, S.C. 1996, c. 23, ss.22, 23. Parental leave The parent has a right to • Reinstatement • Continuation of benefit plans • Continuation of seniority Protection for sex workers • The Criminal Code prohibition against bawdy houses and living off the avails of prostitution increases the risk of physical harm to sex workers. • “[T]he law cannot operate in a manner to increase a risk of harm. The law is supposed to protect us, and protect our vulnerabilities.” (Professor Alan Young, Lead counsel for the three sex workers) Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford, 2012 ONCA 186. Protection for sex workers “Any measure that denies an already vulnerable person the opportunity to protect herself from serious physical violence, including assault, rape and murder, involves a grave infringement of that individual’s security of the person.” Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford, 2012 ONCA 186, at para. 360. Protection for sex workers The Court of Appeal gave Parliament one year to amend the Criminal Code for it to comply with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Income replacement Federal income replacement system is available when a worker is: • Temporarily unemployed • Temporarily disabled • On pregnancy or parental leave • Temporarily caring for a family member who is gravely ill Canada Pension Plan • Based on contributions made during time in paid workforce. • Can be split between spouses where one spouse was not in paid workforce. Canada Pension Plan, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-8, s. 55.1. Church House Conference Centre London