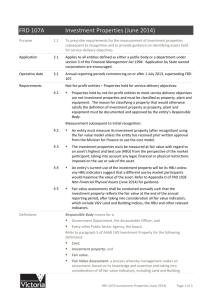

Australian Accounting Standard AASB 15 Revenue from Contracts

advertisement