VAIL (Tutor Virtual Academic Integrity Laboratory). - E

advertisement

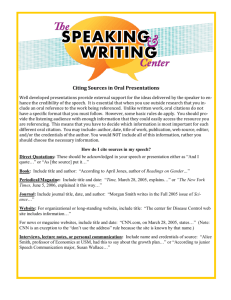

VIRTUAL ACADEMIC INTEGRITY LABORATORY (VAIL) LECTURER Prof. DR. Gunawan, M.pd By JALIUS MD ENGLISH DEPARTEMENT GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION SARJANAWIYATA TAMANSISWA UNIVERSITY 2013 A. Introduction In writing academic paper, the writer will find problem to explore the resources to create as the paper work or assignment , and it make them tend to citate or quote from other books, jurnals or other paper paper work. But the main problem is when writer citate some resources related to the topic of his/her paper work, writer do not attached the name, year or pages from original resources, for this case it can be reputed as plagiarism. In academic paper, quoting some resources there is policies to avoid writer reputed as cheating or plagiarism work. In this paper writer will explore some policies or rules regarding to plagiarism, got at VAIL ( Virtual Academic Integrity Laboratory). The sources explored from internet website of : http://www.umumc.edu/library/vail B. Discussion VAIL (Tutor Virtual Academic Integrity Laboratory). The Virtual Academic Integrity Laboratory 4. 3. 2. 1. MODULE. Module 4. Frequently Asked Questions - Example - Glossary Helping Students Avoid Plagiarism Promote Academic Integrity to Students Inform students of NLU's Policy on Academic Dishonesty. Include a statement on plagiarism in your syllabus (see Sample Syllabus Statement below). Set clear standards for assignments, citations, and grading. Educate Students in Research Practices Explain the value of using various types of sources to strengthen arguments and develop ideas. Teach students how to differentiate between quoting and paraphrasing; give examples of properly paraphrased and cited texts. Make sure your students have the proper research skills to do the assignment. Consider asking a librarian to come to your class to show them how to find and evaluate appropriate sources. Help Students with Documentation Styles Explain the purpose and benefits of correct citation format. Show them the citing sources tutorials and resources available through the NLU Library and Learning Support. Adapted from UMUC Effective Writing Center, "Helping Students Avoid Plagiarism" http://www.umuc.edu/ewc/faculty/avoidingplagiarism.shtml and Binghamton University Libraries, "Preventing Plagiarism: for Faculty & Teaching Assistants"http://library.lib.binghamton.edu/instruct/plagfaculty.htm Preventing Academic Dishonesty and Designing Assignments Designing Plagiarism-Resistant Assignments: Best Practices Faculty can help their students with academic integrity by first designing assignments that are plagiarism-resistant. Research shows that careful assignment design can go a long way to preventing plagiarism (Cummings, 2003; see also Gibelman, Gelman, & Fast, 1999); Malouff & Sims, 1996; Kloss, 1996) Here are some techniques for designing plagiarism-resistant assignments: 1. Consider dropping the open-topic theme. The more specific the assignment, the smaller the universe of information students can use to search and perhaps use inappropriately. 2. Know your field of research. If you require your students to do research, be sure that you have done the research yourself in advance. You will be familiar with many of the sources your students are using and you might recognize suspicious wording, etc. And if you demonstrate to your students that you have done the research yourself, you show your own commitment to the topic. You also give them reason to know that you won’t be fooled, and this in itself can discourage academic dishonesty. 3. Word assignments precisely. It might not be enough to tell your students to cite their sources. You might also need to assign them the specific citation style, give them examples, and point out resources where they can get help. The VAIL Guide to Citation gives detailed instructions for citing common publication types, and it points to other resources as well. 4. Incorporate information literacy standards into your assignments, particularly the need to critically evaluate information, synthesize it and use it, rather than simply collect it and quote it, paraphrase it, or summarize it. The American Library Association has put together a fine resource defining information literacy and listing the five competencies at Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. 5. Become familiar with the student’s “voice.” Have your students write early in the semester or term. A potent signal that a student may have plagiarized is a sudden change in language, style, and “voice,” i.e. the way a student sounds in their writing. The VAIL Guide to Plagiarism Alarms gives a good overview of this and other signals that plagiarism may have occurred. 6. Structure long writing assignments in small chunks or drafts so that students can make incremental progress and not be led down the path of procrastination and plagiarism due to panic. Procrastination is a leading reason why students plagiarize in the first place (Roig & DeTommaso, 1995) 7. Assign annotated bibliographies, requiring students to provide abstracts of their sources in their own words. Librarians at Cornell University have put together a fine resource on the process at How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography. 8. Have students turn in a log or journal of their research, including the names of the search tools used (catalog, search engine, subscription database) and search terms used. Sample their tools and strategies by trying to replicate a few at random. Ask questions if the search cannot be replicated. The University of Maryland University College instituted an undergraduate course, Information Literacy and Research Methods, in which the development of such a research log is a central focus. 9. Discuss student papers in class. Ask questions about the meaning of suspicious passages. If students cannot explain what they have written, perhaps they are not the true author. If students know in advance that they might be required to discuss their papers, this may deter some from plagiarizing. 10. Assign oral presentations. Have your students report on their research process. Prompting students with questions like “How did you find this article you cite? I would like to read it myself,” is a non-threatening way to begin looking into suspicious passages that are not in your student’s voice. 11. Substitute a short written assignment for the oral presentation. This can be a brief, one-page summary of their research process, including how they selected their sources. Ask students to sum up what they learned from their research. 12. Require recent sources, including some that are in print. If you only require Web-based research, this is more likely to tempt students to copy and paste the words of others since it can be easily done. 13. Assign students roles or specific audiences to address in their writing. The papers that can be found in most term paper mills are just that, i.e. term papers, and they are usually written in the third person with the teacher as the audience. If you assign your students roles as a researcher, someone advising an administrator who needs to make a decision, then it is unlikely that it will have the sound of a term paper. In conclusion, designing assignments that are meaningful and challenging gives your students an incentive to learn, and when they have that incentive, they will do their own work. Academic Honesty and Learning Outcomes Higher education requires proper attribution for the source of quotations, paraphrases, and summaries in the text of papers—within the body of the paper and in the reference list. Some reasons for the attribution requirement are to: 1. Distinguish your original work from borrowed work. 2. Assist the reader in locating information for further research. 3. Add authority and context to your own writing. 4. Properly acknowledge the work of others. 1. Distinguish your original work from borrowed work Your faculty members are charged with evaluating and certifying genuine learning outcomes- a combination of knowledge and abilities that you are expected to acquire in your studies. What did you learn as opposed to what did you quote or restate? This would be a nearly impossible task without some means of differentiating between what is our original contribution and what is a quotation, paraphrase, or summary of someone else's written expression or ideas. 2. Help the reader locate information Well-written citations lead you to the sources that support or illuminate what you are reading or writing. It is frustrating to read an incomplete citation that does not help you find the original work being referenced. You have a responsibility to your reader, just as other writers have a responsibility to you, when they write or publish, to assemble an accurate list of the works used within your narrative at the end of your paper. 3. Add authority to your own writing When you provide good in-text citations and references that help the reader find the original text, you are adding value to your paper! You are pointing to something that lends authority and credibility to what you wrote. You are demonstrating that you are not out on a limb or in left field writing about something without any scholarly basis or facts to support your argument. You are demonstrating that someone else has written on the same subject with a similar point of view or that you are willing to consider viewpoints that may be different from your own. This process lends credibility to your writing. 4. Properly acknowledge the original author's work All of us are both creators and users of intellectual property, our academic integrity standards place a high value on recognizing creators as well as making it clear what is our own original contribution! That recognition is sort of a reward for the fruit of our labors. Well-written in-text and bibliographic citations give credit to the creator. This acknowledgement through documentation is expected in higher education and is fundamental to the continuous cycle of research. Citation, Citation, Citation! Practical Reasons for Learning Citation Here are a few practical reasons for learning proper citation. Learning to properly cite will help assure that you get credit for your original contributions as well as credit for understanding how important this value really is to the higher education culture. Without proper citation, you may even be accused of plagiarism! Faculty are Aware of Students’ Misconceptions about Plagiarism Many students have misconceptions about using material they find on the Internet and other electronic sources such as subscription databases. Do not fall prey to these misconceptions. Misconceptions about Plagiarism and Internet Resources If it's on the Internet, it was put there for free and to be used in any manner. Unless the Web site specifically claims this to be the case, you should treat the material as though it were a print resource such as a book or a journal article. Just as you would not quote from a print source or claim the printed work of another as your own, the same applies for Web resources. The reason for this is that the material is copyrighted by another person. If no author is named and no date of publication is given, then I can copy it and claim it as my own. This does not mean that you are the author and can claim it as your own! Actually, there are guidelines for citing material when no author or date are given. See the Citation Examples section of this guide for samples. Faculty are Aware of Term Paper Mills There is a growing body of literature on the subject of plagiarism, including how often it happens, and how easy it is to commit. Plagiarize at your own risk! Faculty are aware that some students copy and paste text from the Internet and sometimes even fall to the temptation of buying a ready-made term paper from a Term Paper Mill. Institutions are Using Software to Detect Plagiarism Institutions are taking plagiarism seriously. Some are now using services to help detect plagiarism. Some services store large collections of term papers that are voluntarily submitted, retrieved from term paper mills or simply posted on the World Wide Web, etc. Faculty may send a student’s term paper to the service to be checked against its database. The service can detect matches in text and generate reports for the faculty on the originality of the submitted term paper. Institutions are Discussing Policies to Prevent, Detect, and Address Plagiarism Now that you know that many faculty are aware of the problem of plagiarism, you should be also be aware that their institutions’ administrators are grappling with ways to prevent, detect, and address plagiarism. Conclusion: Writing originally and learning to cite properly will help you avoid being suspected of plagiarism! Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarizing Here are some guidelines for properly quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing someone else’s text in the APA citation style. For in-text-examples in MLA, please see the UMUC library MLA In-text citations webpage. For additional APA examples please see the UMUC library APA In-text citations webpage. The quote, paraphrase, and summary are from the following source: Source: Fossey, D. (1983). Gorillas in the mist. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin. Quoting If you quote another work word-for-word, you must put this passage in quotation marks and use an in-text citation as well as a full citation at the end of your paper. Example "This unique observation provides only one example of the strong maternal inclinations of female gorillas. An amazing aspect of the incident was that Effie, whose back was turned toward her infant, was aware of Poppy’s silent plight even before the human onlooker facing both animals realized that something was amiss" (Fossey, 1983, p. 89). Paraphrasing Paraphrasing is putting another person’s words in your own words. You may wish to paraphrase in order to maintain your particular style of phrasing things. Paraphrased material must be cited! Example In Gorillas in the Mist, Fossey (1983) gives an example to demonstrate that gorillas are very protective mothers. As a tiger approached her offspring Effie, a mother gorilla, sensed the danger even though she was not facing Effie. The researcher observing them did not notice the danger, but the mother gorilla’s vigilance allowed her to take steps to save the baby gorilla (p. 89). Summarizing Summarizing is condensing another person’s words so that you present the basics of what has been said. A common instance of summarizing is annotating a list of bibliographic sources for a paper. The summary or annotation presents the heart of the material being described. It also needs to be properly cited! Example In Gorillas in the Mist, Fossey (1983) illustrates that female gorillas instinctively protect their offspring as much or more so than female humans (p. 89). You may wish to test your knowledge of quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing by looking at Eight Guidelines to Help You Avoid Plagiarism. Citation Examples: APA and MLA Style Here are some general tips to keep in mind when using APA or MLA style. Use these patterns of capitalization, punctuation, use of italics, and spacing. General Tips to Keep in Mind: APA Style When using APA style, remember to: Indent the second line of the citation five spaces from the left margin. Italicize the title of a book or a journal, regardless of whether it is in print or available electronically. Alphabetize entries letter by letter in your reference list at the end of your paper. Use the author's first initial, never the entire first name. Here are some of the most commonly used citation formats in APA and MLA styles: Articles from Journals and Magazines APA MLA Books APA MLA Doctoral Dissertations and Master's Theses APA MLA Audiovisual Media APA MLA Websites & Electronic Media APA MLA For more examples, please see the complete Citation Resources & Guides provided by UMUC Information and Library Services. Student Tips for Avoiding Plagiarism through Critical Thinking and Research Skills Introduction This guide is intended to give a quick overview of skills you can adopt to foster academic integrity in your own scholarship. Pointers are given to other VAIL guides for a more thorough treatment of some of the suggestions offered. Simply said the first and most important tips are to... Respect the intellectual sweat of others. This means giving credit for work that is not your own and ensuring you cite others' works both within, and at the end, of your paper or project. Know your campus and departmental policies on academic integrity, academic dishonesty and/or plagiarism. This can usually be found in your student handbook, your course syllabus or sometimes posted online in student services resources. Ask a campus representative for assistance. For more on academic integrity policies see the VAIL guide on Academic Policies. Thinking About the Assignment Discuss the requirements of the assignment, your topic, and your research progress with your instructor as needed. Simple mistakes can be avoided by understanding the assignment. It is okay for beginning scholars to ask questions to clarify research terms and language. Research rarely happens in a vacuum, scholars ask many questions and consult with others about their research. Make note of any special requirements including citation style and format requirements. Some instructors require students use only journal articles, web pages, government studies, etc. Know the instructor's parameters for the assignment before you begin. Begin the research early so you are not rushed in the end. Build in time for planning and thinking about the project in the beginning and as you research your topic. Questions to ask yourself in the planning phase: What am I looking for? Who is likely to publish information about it? Where can I find this information? Am I expected to take on a specific role as the author? ...like a scientific or social science researcher? Am I a reporter? Am I supposed to be a neutral observer? Support a specific position or opinion? The Research Phase Save yourself time and frustration by keeping a thorough record of your research, a Research Journal should include the following: where you looked (on the free web, in a research database, etc.) your search terms (subject headings or keywords used) what you found where you found it (book, a free web site, a full-text database, etc.) what you learned diligently recording quotations and paraphrases complete citations for every source Devise a way to visually highlight the words of others in your notes to distinguish them from your words. Use different colored pens or indent every time you paraphrase or quote someone. Diligently put all the words of someone else in quotations ("") and write a bibliographic citation for the original source. Do not wait until you are writing your final paper to assemble bibliographic citations. IMMEDIATELY follow any written notes with a complete bibliographic citation for the author and source or the original text while you are taking notes (not at the end of writing your paper). For more information see the VAIL guide titled Citation! Citation! Citation! Questions to ask yourself in the planning phase: Who is the author? What is the author saying? Why is the author saying this? Do other authors disagree? Use note cards or a word processor and fill out a form like this for each resource you consult: Source Read: What it said: Check Paraphrase or Quote: Insert paraphrase or direct quotation My thoughts or reactions: Reviewing Your Sources Don't Panic! If you've kept your research log, checked your work, and followed the tips in this guide, let your instructor know. This will likely help you and him/her to evaluate your work fairly. Go back to your research log and any annotated bibliographies or research notes. Is the text in question in your notes? Did you mention the author? Is the text in question simply a re-phrasing of the original author's words? If so, properly site the item. Check your campus policies for potential sanctions. For more on policies see the VAIL guide titled Academic Policies. Share your self-evaluation with your instructor, department chair or dean. Your Drafts & Final Writing Give credit where credit is due! Always give proper attribution to all works, words or thoughts that are not your own. This includes but is not limited to: graphs, charts, graphics, pictures from the web, websites, plays, articles, speeches, handouts, e-mails, listserve or bulletin board discussions, online notes, class lectures, movies, computer programs, textbooks, encyclopedia articles, music clips and sounds files. Recognize that you must acknowledge the work of others in two places within your writing: o within the paragraphs of your paper and o at the end of the paper in a Bibliography or Works Cited List. Click here for an example. Use quotation marks when you use someone else's words exactly as they said or wrote them. o See the VAIL Guide titled Citation! Citation! Citation! and the VAIL Tutor for more on using direct quotations in the text of your paper. Provide parenthetical references for all thoughts that are not your own but you have put into your own words. o See the VAIL Guide titled Citation! Citation! Citation! and the VAIL Tutor for more on paraphrasing. Secure style manual for the documentation style (ALA, MLA, etc.) you have been assigned to use for your Bibliography or Works Cited List. Identify the item in hand. o Is it a book, an article from a subscription database, a dissertation, personal letter, e-mail messages, etc...? Apply the rules for formatting in the appropriate documentation style for the resource used. Consult your instructor or librarian if you need assistance. o Libraries keep multiple copies of citation manuals and often write quick help guides such as this one to help you get started properly citing resources. Write at least one draft! Expect to make mistakes. The draft process can help reduce obvious unintentional mistakes. See if your school has a center for writing assistance or offer peer-tutors. Check Yourself! Double-check your final writing against the original text to guarantee that you have properly cited research. Review your research journal and all notes. Compare your draft to your journal. Verify that you have correctly attributed all words and ideas. Have a writing counselor read your drafts or final paper and edit before submission for a grade. Plagiarism detection services such as TurnItIn.com or EduTie.com can be an effective self-evaluation tool. o These services allow you to compare your writing against a large and growing database of student papers, scholarly writing, web sites and web resources. Questions to ask yourself in the drafting phase: o What do my notes say about this idea? o Where did I find that information? o Am I using a paraphrase or a quotation? o What do I think about this idea? Reviewing Your Sources Don't Panic! If you've kept your research log, checked your work, and followed the tips in this guide, let your instructor know. This will likely help you and him/her to evaluate your work fairly. Go back to your research log and any annotated bibliographies or research notes. Is the text in question in your notes? Did you mention the author? Is the text in question simply a re-phrasing of the original author's words? If so, properly site the item. Check your campus policies for potential sanctions. For more on policies see the VAIL guide titled Academic Policies. Share your self-evaluation with your instructor, department chair or dean.