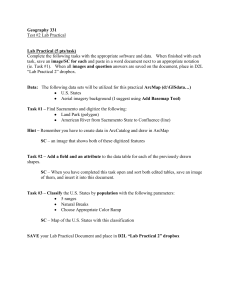

Food Bank Thesis - Sacramento - The California State University

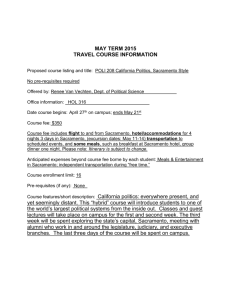

advertisement