NPARIH Review of Progress - Department of Social Services

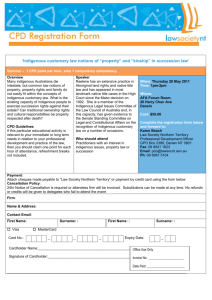

advertisement