iconoclasm - The 5 Minute Classroom: Key Terms for

advertisement

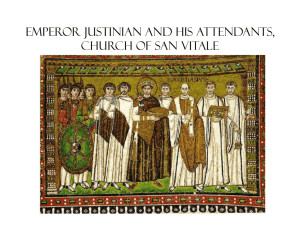

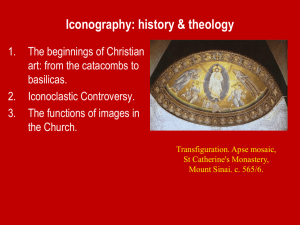

Brain Warm-up! “The concept of iconoclasm entails a contestation over – and destruction of- images coinciding with a belief in the fallacious nature of their representation. The objection to the representation can stem from any number of factors – disagreement over the truth of the representation’s referent, with the manner in which the referent is depicted, etc. – but the commonality between all of these factors is that the violence tends to be directed upon the medium itself.” – Matt Eatough, University of Chicago Take a minute and ponder/discuss what you think this means. Study objectives: 1. Define the term iconoclasm. 2. Apply the definition to practical examples. 3. Describe how this relates to Communication studies and everyday life. 1. The rejection or destruction of religious icons as heretical. 2. The action of attacking or rejecting cherished beliefs and institutions or established values and practices. 3. The distrust and deliberate suspicion of religious imagery; the destruction of various types of icons. Example 1: The First Iconoclastic Period The first example of iconoclasm can be dated back to the 730s, during the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Leo the 3rd began a campaign to remove images of Jesus from prominent places in his cities, claiming that it was heresy to replicate and worship these idols. One such image was located on the entrance gate to the Great Palace of Constantinople, which he had replaced with a cross. Opponents of the idea (called ‘iconocludes’) went so far as to murder some of those people assigned to the task of replacing the image. Example 2: Islamic Iconoclasm This concept is also deeply rooted in Islamic belief. The religion mainly focuses on the avoidance of images of anything viewed as sacred; especially in holy places. However, the act of destroying these images is considered by many Muslims to be an act of great faith and importance. The first example of Muslim iconoclasm is dated back to 630. In a sacred house (Kaaba) in Mecca, several statues of Arabian dieties were completely destroyed. Though not confirmed, the destruction of the Great Sphynx’s nose was said to be an act of iconoclasm carried out by a Sufi Muslim in the mid 1300s. (This is just one of many theories on the fate of the missing nose.) Both of these examples deal with the basic idea of iconoclasm – religious imagery is bad. Boiled down, these cultures (and many more) view the physical representations of their divine beings to be a betrayal of faith. And if faith is defined as “a firm belief in something for which there is no proof” (MerriamWebster Dictionary), then trying to create proof of the divine through these images and physical representations takes away one of the basic tenants of faith. After all, can mere mortals be trusted to accurately depict the divine when they’ve never seen it? Great, but just what exactly does this have to do with the study of communication? Good question. Let’s take an in-depth look at one more example. Example 3: Slightly More Recent History There used to be a statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square in Baghdad. That is, before it was toppled by a United States M88 armored vehicle in the middle of an Iraqi riot. This took place on April 9th, 2003 and was immediately picked up by news sources and spread like wildfire. Not long after that, there were several theories that the event may have been staged. One newspaper had published a picture that had supposedly been altered to show a larger crowd; another report said that the idea had been an American one and not one generated by the Iraqi civilians (as it was made out to be). This is a great example for two reasons: While not exactly a religious image, the statue of Saddam Hussein did represent something: his government. The destruction of the statue therefore represents the destruction of the Hussein government, and a very clear contradiction to the reports that Iraq was winning the war. So here, we have the destruction of the image itself and the destruction of idea that it symbolized. 2. The story itself is adds another layer. As soon as it made the news, the public began to critique it. The event became a distrusted idea. 1. Awesome. Now get to the point. Let’s take another look at that quote: “The concept of iconoclasm entails a contestation over – and destruction of - images coinciding with a belief in the fallacious nature of their representation.” If we go back to the very basics of communication studies, it’ll look something like this: Person 1 M E D I A Person 2 Here we see two people communicating through the use of a medium. But what happens when we lose trust in the medium that is used to communicate something to us? Bingo. That’s the basics of iconoclasm as it relates to us. As soon as we lose faith in the ability of the media to relay the truth to us, we engage in distrust and suspicion of that media. In essence, we no longer believe it to be a valid method of communication. This applies to any kind of media; not just religious images. So… we need to revise our definition of iconoclasm as it relates to communication. Let’s define communicational iconoclasm as the distrust and deliberate suspicion of any kind of image-based media. And exactly how does that relate to us? In our society, the two biggest types of media are television and the internet. It’s the very nature of these types of media that allows for such suspicion and distrust. How can we be sure that these mediums are telling us the truth when so much of the truth depends on the entire picture? And how are we supposed to get the entire picture if we aren’t there? In summation: Iconoclasm has traditionally been defined as “the distrust and deliberate suspicion of religious imagery; the destruction of various types of icons”. A classic example of this is the first iconoclastic period during the Byzantine Empire, where images of deities were thought to be heretical. However, when applied to communications, the idea evolves into a distrust of image media. “Technology has taken away our faith and replaced it with doubt; a need to question all we cannot touch.” - Anonymous Džalto, D. (n.d.). Iconoclasm. Retrieved from http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/iconoclasm.html Eatough, M. (n.d.). Iconoclasm. Retrieved from http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/iconoclasm.htm Farrell, S. (2008, December 11). Retrieved from http://atwar.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/12/11/photographers-journalfirdos-squares-symbols-then-and-now/ Iconoclasm. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.google.ca/search?q=iconoclasm&oq=iconoclasm&aqs=chr ome.69i57j69i60l4j69i59.1710j0&sourceid=chrome&espvd=210&es_sm= 93&ie=UTF-8 Merriam-Webster Dictionary Straw, W. (2011). Intersections of media and communications. Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Limited.