B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas

advertisement

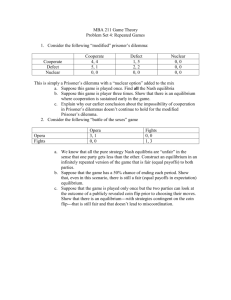

Deep Thought If I ever went to war, instead of throwing a grenade, I’d throw one of those small pumpkins. Then maybe my enemy would pick up the pumpkin and think about the futility of war. And that would give me the time I need to hit him with a real grenade. ~ Jack Handey. (Translation: Today’s lesson demonstrates why people might not cooperate or collude even if it is in their best interests to do so.) BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 1 Readings Readings Baye “Oligopoly” (see the index) Dixit Chapter 4 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 2 Overview Overview BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 3 Overview The Prisoners’ Dilemma shows why people might not cooperate even if it is profitable. Cournot duopoly is a prisoners’ dilemma. Lower output by all is profitable but lower output by you is unprofitable. Duopoly with Substitutes is a prisoners’ dilemma with firms simultaneously choosing prices and producing gross substitutes. Profitable cooperation raises prices. Duopoly with Complements is a prisoners’ dilemma with firms simultaneously choosing prices and producing gross substitutes. Profitable cooperation lowers prices. Advertising is a prisoners’ dilemma when advertising mostly transfers customers between firms rather than generating new customers. Profitable cooperation reduces advertising. Cleaning and Other Public Goods are prisoner dilemmas when public good purchases by all is profitable but purchases by you are unprofitable. Profitable cooperation increases good purchases. Noise and Other Externalities can be prisoner dilemmas. Profitable cooperation decreases the negative externalities (like noise) and increases the positive externalities (like entertainment). BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 4 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 5 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma Overview The Prisoners’ Dilemma shows why people might not cooperate even if it is profitable. Cournot duopoly is a prisoners’ dilemma. Lower output by all is profitable but lower output by you is unprofitable. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 6 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma Comment: A Prisoners’ Dilemma demonstrates why people might not cooperate or collude even if it is in their best interests to do so. The strongest form of the prisoners’ dilemma is when non-cooperation is a dominate strategy for each person. The first game called a “Prisoners’ Dilemma” described prisoners, and has been used in law enforcement. The solution to that game also solves a variety of business applications. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 7 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma In the original dilemma, two suspects are arrested by the police. The police have insufficient evidence for a conviction, and, having separated both prisoners, visit each of them to offer the same deal. If one confesses for the prosecution against the other and the other remains silent, the confessor goes free and the silent accomplice receives the full 10-year sentence. If both remain silent, both are sentenced to only six months in jail for a minor charge. If each confesses against the other, each receives a five-year sentence. Each prisoner must choose to confess or to remain silent. Each one is assured that the other would not know about the betrayal before the end of the investigation. How should each prisoner act? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? If so, can each trust the other to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 8 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma One way to write the normal form of the game is for payoffs to be the negative of the number of years of imprisonment. Prisoner B Prisoner A Confess Silent Confess -5,-5 0,-10 Silent -10,-10 -.5,-.5 Each prisoner should confess since it is the dominate strategy. Prisoners would both increase their payoff, from -5 to -.5 (gaining 4.5), if they each cooperated and remained silent. Neither prisoner can trust the other to cooperate and remain silent since Confess is the best response to the other prisoner remaining Silent. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 9 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma Question: Verizon and AT&T control a large share of the U.S. telecommunications market. They simultaneously decide on the size of manufacturing plants for the next generation of smart phones. Suppose the firms’ goods are perfect substitutes, and market demand defines a linear inverse demand curve P = 20 – (QV + QA), where output quantities QV and QA are the thousands of phones produced weekly by Verizon and AT&T. Suppose unit costs of production are cV = 2 and cA = 2 for both Verizon and AT&T. Suppose Verizon and AT&T consider any quantities QV = 4.5 or 6, and QA = 4.5 or 6. What quantity should Verizon choose in this Cournot Duopoly? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? Can Verizon trust AT&T to cooperate? Can AT&T trust Verizon to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 10 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma Answer: To begin, fill out the normal form for this game of simultaneous moves. For example, at Verizon quantity 4.5 and AT&T quantity 6.0, price = 20-10.5 = 9.5, so Verizon profits = (9.5-2)4.5 = 33.75 and AT&T profits = (9.5-2)6 = 45. AT&T Verizon 4.5 6.0 4.5 6.0 40.5,40.5 33.75,45 45,33.75 36,36 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 11 Example 1: The Prisoners’ Dilemma AT&T Each player should choose 6 4.5 6.0 since it is the dominate 4.5 40.5,40.5 33.75,45 strategy for each player: Verizon 6.0 45,33.75 36,36 6 gives better payoffs for that player compared with 4.5, no matter whether the other player chooses 4.5 or 6. There are mutual gains if both Verizon and AT&T cooperate and produce 4.5. But Verizon cannot trust AT&T to cooperate because AT&T cooperating and choosing 4.5 is not a best response to Verizon cooperating and choosing 4.5. Likewise, AT&T cannot trust Verizon to cooperate because Verizon cooperating and choosing 4.5 is not a best response to AT&T cooperating and choosing 4.5. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 12 Example 2: Duopoly with Substitutes Example 2: Duopoly with Substitutes BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 13 Example 2: Duopoly with Substitutes Overview Duopoly with Substitutes is a prisoners’ dilemma with firms simultaneously choosing prices and producing gross substitutes. Profitable cooperation raises prices. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 14 Example 2: Duopoly with Substitutes Question: MillerCoors and Anheuser-Busch control a large share of the U.S. Domestic beer market. The unit cost of a keg to both retailers is $75. The retailers compete on price but consumers do not find the goods to be perfect substitutes. Suppose MillerCoors and AnheuserBusch consider prices $85 and $95. If both choose price $85, each has demand 50; if both $95, each has 40; and if one chooses $85 and the other $95, the lower price has demand 85 and the higher price 5. Are the two goods gross substitutes or gross complements? What price should MillerCoors choose in this Price Competition Game? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? Can MillerCoors trust Anheuser-Busch to cooperate? Can Anheuser-Busch trust MillerCoors to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 15 Example 2: Duopoly with Substitutes Answer: To begin, fill out the normal form for this game of simultaneous moves. For example, at Miller price $95 and Busch price $85, Miller’s demand is 5 and Busch’s is 85, so Miller profits $(95-75)x5 = $100 and Busch profits $(85-75)x85 = $850. Goods are gross substitutes because a higher price for one means higher demand for the other. Busch Miller $85 $95 $85 500,500 100,850 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas $95 850,100 800,800 16 Example 2: Duopoly with Substitutes Each player should choose $85 since it is the dominate strategy for each player: $85 it gives Miller better payoffs for that player compared with $95, no matter whether the other player chooses $85 or $95. Busch $85 $95 $85 500,500 100,850 $95 850,100 800,800 There are mutual gains if both MillerCoors and Anheuser-Busch cooperate and charge $95. But MillerCoors cannot trust AnheuserBusch to cooperate because Anheuser-Busch cooperating and choosing $95 is not a best response to MillerCoors cooperating and choosing $95. Likewise, Anheuser-Busch cannot trust MillerCoors to cooperate because MillerCoors cooperating and choosing $95 is not a best response to Anheuser-Busch cooperating and choosing $95. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 17 Example 3: Duopoly with Complements Example 3: Duopoly with Complements BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 18 Example 3: Duopoly with Complements Overview Duopoly with Complements is a prisoners’ dilemma with firms simultaneously choosing prices and producing gross substitutes. Profitable cooperation lowers prices. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 19 Example 3: Duopoly with Complements Question: Wii video game consoles are made by Nintendo, and some games are produced by third parties, including Sega. The unit cost of a console to Nintendo is $50, and of a game to Sega is $10. Suppose Nintendo considers prices $250 and $350 for consoles, and Sega considers $40 and $50 for games. If they choose prices $250 and $40 for consoles and games, then demands are 1 and 2 (in millions); if $250 and $50, then .8 and 1.6 (in millions); if $350 and $40, then .7 and 1.4 (in millions); and if $350 and $50, then .6 and 1.2 (in millions). Are the two goods gross substitutes or gross complements? What price should Nintendo choose if both companies choose simultaneously? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? Can Nintendo trust Sega to cooperate? Can Sega trust Nintendo to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 20 Example 3: Duopoly with Complements Answer: To begin, fill out the normal form for this game of simultaneous moves. For example, at Nintendo price $350 and Sega price $40, Nintendo’s demand is .7 and Sega’s is 1.4, so Nintendo profits $(35050)x.7 = $210 and Sega profits $(40-10)x1.4 = $42. Goods gross complements because a higher price for one means lower demand for the other. Sega Nintendo $250 $350 $40 200,60 210,42 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas $50 160,64 180,48 21 Example 3: Duopoly with Complements Nintendo should choose $350 since it is the dominate strategy, and Sega should Nintendo choose $50 since it is the dominate strategy. Sega $250 $350 $40 200,60 210,42 $50 160,64 180,48 There are mutual gains if both Nintendo and Sega cooperate and charge their lower price. But Nintendo cannot trust Sega to cooperate because Sega cooperating and choosing $40 is not a best response to Nintendo cooperating and choosing $250. Likewise, Sega cannot trust Nintendo to cooperate because Nintendo cooperating and choosing $250 is not a best response to Sega cooperating and choosing $40. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 22 Example 3: Duopoly with Complements Comment: The dilemma with Sam’s and Costco producing gross substitutes is the dominate strategy for each prices goods too low. The dilemma with Nintendo and Sega producing gross complements is the dominate strategy for each prices goods too high. Costco Sam's $85 $95 $85 500,500 100,850 $95 850,100 800,800 Sega Nintendo $250 $350 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas $40 200,60 210,42 $50 160,64 180,48 23 Example 4: Advertising Example 4: Advertising BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 24 Example 4: Advertising Overview Advertising is a prisoners’ dilemma when advertising mostly transfers customers between firms rather than generating new customers. Profitable cooperation reduces advertising. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 25 Example 4: Advertising Comment: Advertising is a real life example of the prisoner’s dilemma. When cigarette advertising on television was legal in the United States, competing cigarette manufacturers had to decide how much money to spend on advertising. The effectiveness of Firm A’s advertising was partially determined by the advertising conducted by Firm B. Likewise, the profit derived from advertising for Firm B is affected by the advertising conducted by Firm A. If both Firm A and Firm B chose to advertise during a given period the advertising cancels out, receipts remain constant, and expenses increase due to the cost of advertising. Both firms would benefit from a reduction in advertising. However, should Firm B choose not to advertise, Firm A would benefit by advertising and Firm B would lose. As in any prisoner’s dilemma, each player cannot trust the other to cooperate. In the case of cigarette advertising, that lack of trust made cigarette manufacturers endorse the creation in the U.S. of the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act banning cigarette advertising on television, understanding that this would reduce costs and increase profits across the industry. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 26 Example 4: Advertising Question: R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Corp. and Philip Morris Corp. must decide how much money to spend on advertising. They consider spending either $10,000 or zero. If one advertises and the other does not, the advertiser pays $10,000, then takes $100,000 profit from the other. If each advertises, each pays $10,000 but the advertisements cancel out and neither player takes profit from the other. Should R.J. Reynolds spend $10,000 or zero on advertising if both companies choose simultaneously? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? Can R.J. Reynolds trust Philip Morris to cooperate? Can Philip Morris trust R.J. Reynolds to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 27 Example 4: Advertising Answer: To begin, fill out the normal form for this game of simultaneous moves, with payoffs in thousands of dollars. For example, if Reynolds advertises and Philip does not, Reynolds pays $10,000, then takes $100,000 profit from Philip. Hence, Reynolds makes $90,000 and Philip looses $100,000. Write payoffs in thousands of dollars. Philip Reynolds Ad No Ad Ad -10,-10 -100,90 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas No Ad 90,-100 0,0 28 Example 4: Advertising Philip Each player should choose to Ad No Ad advertise since it is the Ad -10,-10 90,-100 dominate strategy for each Reynolds No Ad -100,90 0,0 player: Ad gives better payoffs for that player compared with No Ad, no matter whether the other player chooses Ad or No Ad. There are mutual gains if both Reynolds and Philip cooperate and choose No Ad. But Reynolds cannot trust Philip to cooperate because Philip cooperating and choosing No Ad is not a best response to Reynolds cooperating and choosing No Ad. Likewise, Philip cannot trust Reynolds to cooperate because Reynolds cooperating and choosing No Ad is not a best response to Philip cooperating and choosing No Ad. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 29 Example 5: Cleaning and Other Public Goods Example 5: Cleaning and Other Public Goods BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 30 Example 5: Cleaning and Other Public Goods Overview Cleaning and Other Public Goods are prisoner dilemmas when public good purchases by all is profitable but purchases by you are unprofitable. Profitable cooperation increases good purchases. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 31 Example 5: Cleaning and Other Public Goods Question: Consider a New York City street on which 25 small businesses are run, and which suffers from a serious litter problem that detracts customers. It costs $100 annually for each business to keep the front of their store clean. If a store owner decides to keep the front of their store clean, all businesses on the street will have improved sales and profits. Suppose every business on the street will have a $10 increase in annual profit for each business that decides to keep the front of their store clean. If more than ten businesses clean their storefronts, then all of the businesses will make more money, including the businesses that clean. If some businesses clean but fewer than ten do so, then the businesses that clean will lose money, while the businesses that do not clean will gain money. Should anyone clean if all businesses choose simultaneously? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? Can any business trust the others to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 32 Example 5: Cleaning and Other Public Goods Answer: No one should clean since Not Cleaning is a dominate strategy. For any strategies by each of the other 24 stores, the extra payoff to Store X from cleaning is a $10 increase minus a $100 cost, which makes the payoff $90 less than for Not Cleaning. When each of the 25 stores follows its dominate strategy, no one cleans, and the payoff to each store is 0. But if each of the 25 stores cleans, each receives a $10x25 increase minus a $100 cost, which makes the payoff $150 more than in the dominance solution. But no business can trust the others to cooperate because Store X cooperating and choosing Cleaning is not a best response to all the other stores cooperating and choosing Cleaning. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 33 Example 6: Noise and Other Externalities Example 6: Noise and Other Externalities BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 34 Example 6: Noise and Other Externalities Overview Noise and Other Externalities can be prisoner dilemmas. Profitable cooperation decreases the negative externalities (like noise) and increases the positive externalities (like entertainment). BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 35 Example 6: Noise and Other Externalities Comment: October 23, 2008 marked the date that many downtown Fullerton regulars cried a tear. The Rockin' Taco Cantina was shut down after being served an eviction notice. No more dueling pianos, no more drunk dance floors, no more disorderly conduct outside in the alley. Was government action needed to control disorderly conduct? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 36 Example 6: Noise and Other Externalities Question: Consider a downtown Fullerton street on which 12 bars are run, and which suffers from a serious drunkenness problem that detracts customers because of the violence and smell. It costs $200 daily in foregone profit for each bar to enforce moderation stop serving customers before they become drunk. If a bar owner decides to enforce moderation, all bars on the street will have improved sales and profits. Suppose every bar on the street will have a $20 increase in daily profit for each bar that decides to enforce moderation. If more than ten bars enforce moderation, then all of the bars will make more money, including the bars that enforce moderation. If some businesses enforce moderation but fewer than ten do so, then the bars that enforce moderation will lose money, while the bars that do not will gain money. Should anyone enforce moderation if all bars choose simultaneously? Are there mutual gains from cooperation? Can any bar trust other bars to cooperate? BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 37 Example 6: Noise and Other Externalities Answer: No one should enforce moderation since Not Enforce Moderation is a dominate strategy. For any strategies by each of the other 11 bars, the extra payoff to Bar X from enforcing moderation is a $20 increase minus a $200 cost, which makes the payoff $180 less than for Not Enforce Moderation. When each of the 12 bars follows its dominate strategy, no one enforces moderation, and the payoff to each store is 0. But if each of the 12 bars enforce moderation, each receives a $20x12 increase minus a $200 cost, which makes the payoff $40 more than in the dominance solution. So mutual gains are possible. But no bar can trust the others to cooperate because Bar X cooperating and choosing Enforce Moderation is not a best response to the other bars choosing Enforce Moderation. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 38 Review Questions Review Questions You should try to answer some of the review questions (see the online syllabus) before the next class. You will not turn in your answers, but students may request to discuss their answers to begin the next class. Your upcoming Exam 2 and cumulative Final Exam will contain some similar questions, so you should eventually consider every review question before taking your exams. BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 39 BA 445 Managerial Economics End of Lesson B.6 BA 445 Lesson B.6 Prisoner Dilemmas 40