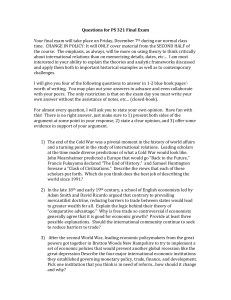

Stanford-Gulati-Rosenthal-Aff-Kentucky

advertisement