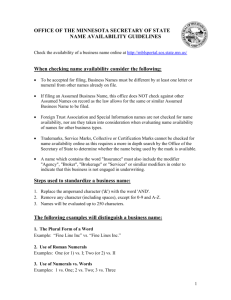

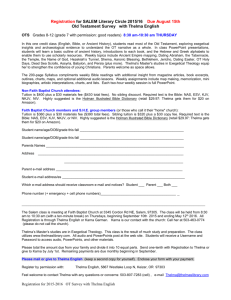

Shot By Shot for Cowboys in Mirror Scene

Shot By Shot for Cowboys in Mirror Scene

1.

Full shot

2.

Medium shot

3.

Traveling shot

4.

Medium long shot

5.

Close up

6.

Medium close up; Slight panning

7.

Medium shot

8.

Medium shot; Pan right

9.

Medium shot (two-shot 1)

Repeat for 5 shots

10.

Closer Medium shot (still two-shot 1)

11.

Closer Medium shot

12.

Medium close up; Pan up (two-shot 2)

13.

Medium close up

14.

Medium close up

15.

Close up

16.

Medium close up; High angle; Pan down (two-shot 3)

17.

Close up

18.

Medium close up (end two-shot 3)

19.

Medium long shot

20.

Traveling long shot

21.

Medium shot

22.

Medium close up (two-shot 4)

Repeat for 2 shots

NOTE: This list should also have a brief description of who/what is in the shot.

Twila McStudent

Dr. Lori Wilson Snaith

Film 2080

27 February 2028

Cowboys in Mirror

Thelma and Louise tells its story with a constant feminist slant as its signature critique on modern and familiar theatrical situations. The scene, “Cowboys in Mirror,” introduces JD as eyecandy and Thelma’s anti-Daryl. In his choice of shots in this scene, Ridley Scott manages to subvert a typical guy-meets-girl scenario with role reversals and unexpected edits.

At the beginning of the scene, we see JD as a little boy playing with his hose. From a literal perspective, this male seems childish and idle. In the metaphorical sense, however, JD’s actions have a sensual, sexual feel to them. Although JD is dressed as a cowboy, stereotypically hardworking, he lazes around at a rest stop or gas station, unemployed and unproductive. At first,

JD seems like just another bump in the road; Thelma literally bumps into JD on her way out of a telephone booth. The camera follows, and even leads, the disoriented Thelma as she tries to escape JD when he is apologizing. Instead of following Thelma all the way back to her convertible, Scott gives one more sneak-peek at JD as he walks away, our gaze lingering on this beautiful man-child. This extra follow up shot acts reassures us that JD will reappear in the movie and possibly become a key character in the narrative.

In the very next shot, we cut to a shot of a shriveled cowboy, and we hear a nondiegetic melody of harmonica and guitar to emphasize the feeling of age and decrepitude. Both elements of this mise-en-scène suggest loneliness and even boredom at the hot desert truck stop.

Furthermore, in re-enforcing this setting of dusty sweatiness, Scott cuts to Thelma, languidly

wiping the sweat off her face with a raggedy tissue. These short vignettes may not add to the plot of the film, but they establish the mood and realism of Thelma and Louise’s journey. . realistic scenery.

Thelma applies eye liner, looking in the rearview mirror of Louise’s convertible as an unfocused JD drifts into the background. Thelma’s movements and expression become slightly agitated as she spots JD through the mirror. She stares at the young man, who we see as an object, because JD is unaware of her gaze upon him. Thelma is the closest character to the camera and thus closer to the audience, while JD is passively on display for her—and our—judgment. The camera follows the still-unfocused JD, who is more of a blur than a human, as Thelma’s eyes follow JD through the succession of mirrors of the convertible. The audience shares Thelma’s point of view as she observes JD while he is deciding to approach her. Scott chooses not to shoot this image such that it focuses on JD and his internal conflict of whether or not to speak to a beautiful, older woman. Instead, Scott subverts the typical male-on-female “gaze” by making the female the subject rather than the object in this case. The shot shifts to Thelma’s point of view when she adjusts the side mirror; the audience sees the mirror and JD’s reflection as he approaches, further objectifying JD because we do not see him in person, but only in reflection.

The alternating shots between Thelma and JD follow their conversation as JD asks for a ride. When Thelma mentions that the car on which JD is now leaning does not belong to her, he immediately removes his hand, as thos the car was someone’s body and it is not his place to touch it…yet. When Thelma offers to persuade her friend, Louise, to let JD ride with them, Scott cuts the shots much more closely, albeit from the same angle. These closer shots during their conversation suggest that the two characters are by no means strangers anymore; because

Thelma initiates the intimacy, she controls the conversation—a further subversion of the typical male-picks-up-female scene that we’re so used to seeing in films and television.

When Thelma asks Louise’s permission to let JD hitch a ride, Scott shows her from

Louise’s point of view, from a slightly higher angle—literally, Thelma is sitting in the car, looking up at Louise, who stands next to it. However, high angle shots also indicate a sense of superiority or authority. Louise, therefore, is in power in this conversation, because she alone decides whether or not JD can join the two of them. She looks down on Thelma for her naiveté in not learning her lesson about how dangerous handsome men can be, even after her narrow escape from being raped earlier in the film. We cut to a wide shot of the convertible peels out of the parking lot, leaving JD in the dust. Louise’s reckless driving is a reflection of her frustration with

Thelma. Thelma complains to Louise because she is equally angry and frustrated that JD is not going with them. Finally, however, Thelma and JD reunite in a steamy sex scene that we hope will lead to a happy ending for poor abused Thelma, but Scott subverts this traditional plot line, depicting JD instead as a whore who services Thelma’s sexual desires solely for financial gain.

The small motifs that create non-verbal narrative in “Cowboys in Mirror” become like other characters in Thelma and Louise, always commenting on the action. The body builder in the background of the filling station is not the only male who has misconceptions of desirable masculinity; the loutish truck driver and the abusive Daryl also try to attract women in the most misogynistic ways. Social blocking and the gaze in this film always operate, however, in favor of the female. Even at the film’s iconic ending, the camera will follow Thelma and Louise off the cliff rather than stay with the males and the cop cars; even in the midst of their spectacular suicide, Thelma and Louise are not objects being observed, but fully self-aware free agents, taking their leave of live on their own terms: airborne...flying into a bright eternity.

Work Cited

Thelma and Louise. Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis. MGM, 1991.

Film