Directions: You will have 4 choices for this final exam essay. You

advertisement

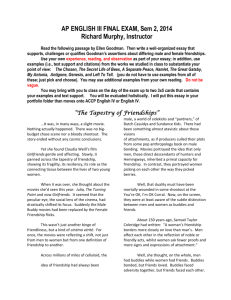

AP English III: Final Exam, Semester 2 -- 2013 Directions: You will have 4 choices for this final exam essay. You may use two 3 x 5 note cards for your outline and quotes in preparation for the writing of the essay in class. Your support for your choice of topic needs to be specific and precise in its detail and articulation. Choice 1: “The Tapestry of Friendships” selection. Essay prompt is on the editorial sheet. Choice 2: in Genesis, the novel questions human being’s capacity to determine its own ends, to use freedom wisely and judiciously, and to develop intelligence and technology constructively. Does the outcome suggest that humans are incapable of creating and managing their own future? Choices 3 and 4 entail the concept of heroism. In literature, a tragic hero is a character who pursues a goal, or dream, admirably, but does not achieve that goal / dream because of a flaw, either within the dreamer or a flaw within society. The nature of the flaw tends to be complex. Choice 3: In Genesis, Anaximander explains to the Examiners, “I believe those who feel the urge to understand Adam’s heroism instinctively understand the importance of empathy. For a society to function successfully, perhaps there needs to be a level of empathy that cannot be corrupted.” Write an essay in which you support, refute, or qualify the argument from Anaximander that Adam is a hero in this future Republic. Choice 4 : In The Great Gatsby, it can be argued that Jay Gatsby is a tragic hero, a pathetically naïve man who relentlessly pursues Daisy Buchanan in hopes of a lasting marriage with her after he returns from the War. At the same time, it can be argued that there are no heroes in Gatsby, only “careless people”, who pursue wealth and materialism relentlessly, “smashing up things and creatures and then retreating back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” Write an essay in which you support, refute, or qualify the argument that indeed there are no heroes in this novel. “The Tapestry of Friendships” Read the following passage by Ellen Goodman. Then write a well-organized essay that supports, challenges or qualifies Goodman’s assertions about differing male and female friendships. Use your own experience, reading, and observation as part of your essay; in addition, use examples (i.e., text support and citations) from the works we studied in class to substantiate your point of view: The Chosen, The Secret Life of Bees, A Separate Peace, Hamlet, The Great Gatsby, My Antonia, Antigone, Genesis, and Left To Tell. (you do not have to use examples from all of these; just pick and choose). You may use additional examples from your own reading. ...It was, in many ways, a slight movie. Nothing actually happened. There was no big-budget chase scene nor a bloody shootout. The story ended without any cosmic conclusions. Yet she found Claudia Weill’s film Girlfriends gentle and affecting. Slowly, it panned across the tapestry of friendship, showing its fragility, its resiliency, its role as the connecting tissue between the lives of two young women. When it was over, she thought about the movies she’d seen this year: Julia, The Turning Point and now Girlfriends. It seemed that the peculiar eye, the social lens of the cinema, had drastically shifted its focus. Suddenly the Male Buddy movies had been replaced by the Female Friendship flicks. This wasn’t just another binge of friendliness, but a kind of cinéma vérité. For once, the movies were reflecting a shift, not just from men to women but from one definition of friendship to another. Across millions of miles of celluloid, the idea of friendship had always been male, a world of sidekicks and “pardners,” of Butch Cassidys and Sundance Kids. There had been something almost atavistic about these visions of attachments, as if producers culled their plots from some pop anthropology book on male bonding. Movies portrayed the idea that only men, those direct descendants of hunters and Hemingways, inherited a primal capacity for friendship. In contrast, they portrayed women picking on each other the way they picked berries. Well, that duality must have been mortally wounded in some shootout at the You’re OK, I’m OK Corral. Now, on the screen, they were at least aware of the subtle distinction between men and women as buddies and friends. About 150 years ago, Samuel Taylor Coleridge had written: “A woman’s friendship borders more closely on love than a man’s. Men affect each other in the reflection of noble or friendly acts, whilst women ask fewer proofs and more signs and expressions of attachment.” Well, she thought, on the whole, men had buddies while women had friends. Buddies bonded, but friends loved. Buddies faced adversity together, but friends faced each other. There was something palpably different in the way they spent their time. Buddies seemed to “do” things together, friends simply “were” together. Buddies came linked, like accessories, to one activity or another. People have golf buddies and business buddies, college buddies and club buddies. Men often keep their buddies in these categories, while women keep a special category for friends. A man once told her that men weren’t real buddies until they’d been “through the wars” together, corporate or athletic or military. They had to soldier together, he said. Women, on the other hand, didn’t count themselves as friends until they’d shared three loathsome confidences. Buddies hang tough together, friends hang onto each other. It probably had something to do with pride. You don’t show off to a friend; you show need. Buddies try to keep the worst from each other; friends confess it. A friend of hers once telephoned her lover, just to find out if he were home. She hung up without a hello when he picked up the phone. Later, wretched with embarrassment, the friend moaned, “Can you believe me? A thirty-five-year-old lawyer, making a chicken call?” Together, they laughed and made it better. Buddies seek approval. But friends seek acceptance. She knew so many men who had been trained in restraint, afraid of each other’s judgment or awkward with each other’s affection. She wasn’t sure which. Like buddies in the movies, they would die for each other, but never hug each other. She’d reread Babbitt recently, that extraordinary catalogue of male grievances. The only relationship that gave meaning to the claustrophobic life of George Babbitt had been with Paul Riesling. But not once in the tragedy of their lives had one been able to say to the other “you make a difference.” Even now, men shocked her at times with their description of friendship. Does this one have a best friend? “Why, of course, we see each other every February.” Does that one call his most intimate pal long distance? “Why, certainly, whenever there’s a real reason.” Do these two old chums ever have dinner together? “You mean alone? Without our wives?” Yet, things were changing. The ideal of intimacy wasn’t this parallel playmate, this teammate, this trench mate. Not even in Hollywood. In the double standard of friendship, for once the female version was becoming accepted as the general ideal. After all, a buddy is a fine life-companion. But one’s friends, as Santayana once wrote, “are that part of the race with which one can be human.”