Example_for_a_good_paper_80___Writting_Sample

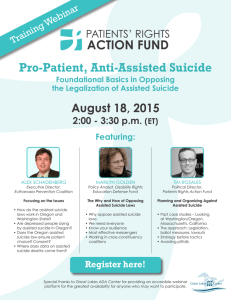

advertisement

LW862: Death and Dying Could physician-assisted suicide be classified as a service under Article 49 of the European Community Treaty? ‘The quality of mercy is not strain’d, It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven.’ William Shakespeare: The Merchant of Venice IV:I:184-185 Introduction Diane Pretty, John Close, Elaine Witt, Reginald Crewe, Debbie Purdy:1 these names represent just a small selection from a considerably longer list of people whom are currently prevented by English law from seeking medical assistance to die and end their intolerable suffering. Notwithstanding widespread public support in the United Kingdom for a change in the law to permit assisted dying for those individuals who are diagnosed with terminal illnesses, 2 the English legal position continues to remain the most restrictive in Europe.3 Furthermore, although the courts in other European jurisdictions such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland have adopted less severe penalties in recognition of the compassionate motive that lies behind a terminally ill person’s request that his life be terminated,4 this approach has not been adopted in the United Kingdom and the English courts still continue to enforce strict criminal penalties against those who actively participate or assist in causing the death of another. Consequently, it can be argued that the current legal position ‘does not provide the support for dignity in dying that many terminally ill patients seek’5 and is ‘out of step with public opinion in the UK and with legal provisions in some other European jurisdictions.’ 6 However, as Mason and Laurie suggest, it is highly unlikely that Parliament will enact any legislation7 that will legalise either active 1 BBC News, 29 October 2008 National Opinion Poll on Euthanasia 2003 in H. Biggs, The Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill 2004: Will English Law Soon Allow Patients the Choice to Die? 12 European Journal of Health Law 43, 2005, p.44 3 This has been emphasised following the decision in R v Woolin [1999] 1 AC 82 where the House of Lords held that intention for the purposes of a charge of murder could be inferred in circumstances where: ‘Death [or seriously bodily harm] was a virtual certainty (barring some unforeseen intervention) as a result of the defendants’ actions and that the defendant appreciated that such was the case’ per Lord Steyn at 97. Consequently, it is clear that a person who actively participates in ending the life of a terminally ill person (irrespective of their compassionate motive) will be satisfy the mens rea for murder as English law does not recognise the defence of mercy killing. Similarly, as discussed below, a person who assists another to commit suicide is also liable under s.2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961 4 H. Biggs, The Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill 2004: Will English Law Soon Allow Patients the Choice to Die? 12 European Journal of Health Law 43, 2005, p.44 5 Ibid, p.52 6 Ibid 7 Particularly following the failure of Lord Joffe’s The Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill 2004 2 LW862: Death and Dying euthanasia or permit physician-assisted suicide.8 Unsurprisingly, the restrictive UK position has led to the development of ‘death tourism’ and in recent years large numbers of desperately ill people have travelled from the UK to more ‘permissive’ jurisdictions in search of assisted dying.9 The most popular destination for those seeking assisted death abroad is the Dignitas Clinic in Zurich, Switzerland, which as of October 2008 has helped over 100 Britons to die.10 However, the increasing numbers of ‘suicide-tourists’ has proven controversial and has led the Swiss Government to consider introducing measures that would restrict the rights of foreigners to assisted suicide.11 Moreover, those individuals who travel with their terminally ill relatives to jurisdictions such as Switzerland where assisted dying is legal, are also at risk of prosecution under s.2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961 upon their return to the UK. Although the Crown Prosecution Service and the Courts have repeatedly asked the Director of Public Prosecutions to issue guidance on the matter,12 no information has been forthcoming and consequently, it is clear that the position of the relatives of a terminally ill individual seeking an assisted death abroad continues to remain uncertain. Notwithstanding these difficulties, it can be argued that European Community (EC) law,13 particularly the right to receive services in another Member State of the Union, may provide an answer to the current problem. This paper will consider whether it is possible to classify physician-assisted suicide (PAS) as a ‘service’ for the purposes of Article 49 EC, which provides for the free movement of services across the EU and requires ‘the removal of restrictions on the provision of services between Member States, whenever a cross-border element is present.’14 Furthermore, if PAS can be classified as a service under EC Law, it is questionable whether the UK Government would be able to deny terminally ill Britons from exercising their rights as EU Citizens15 to obtain PAS in the more permissive jurisdictions of the Union.16 8 J. K. Mason and G. Laurie, Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics, 7th Edition, Oxford, 2005, p.615 H. Biggs, The Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill 2004: Will English Law Soon Allow Patients the Choice to Die? 12 European Journal of Health Law 43, 2005, p.45 10 F. Gibb, Swiss Clinic Has Helped 100 Britons to die, The Times, October 2 2008 11 M. Leidig, P. Sherwell, Swiss to crack down on suicide tourism, Daily Telegraph, 14 March 2004 12 R (on the Application of Pretty) v DPP [2001] UKHL 61 In Re Z (Local Authority: Duty) [2004] EWHC 2817 (Fam), R (on the Application of Purdy) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2008] EWHC 2565 13 The Maastricht Treaty introduced a tripartite ‘pillar’ system into the EU – for the purposes of this paper, the discussion will be focused on Pillar I – The Community Pillar, and accordingly all references are made to European Community Law. 14 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford, 2007, p.791 15 Article 17(1) EC Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union. Article 17(2) EC Citizens of the Union shall enjoy the rights conferred by this Treaty and shall be subject to the duties imposed thereby. 16 Switzerland is not a Member State of the European Union although it does have certain agreements with the EU on free-movement rights 9 LW862: Death and Dying In developing this argument, the author will briefly consider the dichotomy between PAS and euthanasia before examining whether a model such as that operated in Switzerland could be classified as a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC. The current Swiss legal position in respect of assisted-dying will be examined as will the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Communities (ECJ) relating to the free movement of services across the Union. Furthermore, if it is possible to define PAS as service under the auspices of EC law, it will be considered whether the practice could justifiably be restricted under the agreed exceptions to Article 49 EC. Defining Physician-Assisted Suicide This paper contends that EC law should recognise PAS as a service under Article 49 EC. To fully appreciate the implications that this approach would have on the traditional understanding of the law of the single market, it is necessary to firstly, provide a brief discussion of the main issues pertaining to PAS and secondly, consider whether the position taken by the Swiss jurisdiction17 in permitting assisted suicide for terminally ill individuals could be adopted as an EU-wide model for the purposes of Article 49 EC. (A) Physician-Assisted Suicide: Not Always a Simple Case of ‘Leaving the Pills’ Mason and Laurie argue that the ‘classic’ case of PAS involves a doctor ‘in no more than providing the means of ending life’18 –an approach that normally entails the provision or prescription of the appropriate medication and nothing else. It is clear that by taking the medication himself and thus terminating his own life, the patient will complete the act which can then properly be classified as an act of suicide, albeit assisted. In such scenarios the doctor remains a passive agent in the assisted dying relationship and consequently, the process can be considered as a form of passive voluntary euthanasia.19 Moreover, the fact that the physician plays no more than a de minimus role in situations involving PAS is of considerable legal significance. Although the doctor prescribes the drugs, he does not actually perform the final act by administering the lethal dose to the patient. Therefore, it can be argued that as the doctor does not actively end his patient’s life he cannot satisfy the actus reus for the crime of murder.20 Clearly, this approach contrasts greatly with scenarios involving active 17 I am deliberately focusing on Switzerland as it is a European Country, albeit not an EU Member, and as it satisfies the requirements for a service set out in Article 50EC, the Swiss system provides an ideal model for how a system of PAS could be operated as a service under Article 49EC 18 J. K. Mason and G. Laurie, Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics, 7th Edition, Oxford, 2005, p.612 19 Ibid 20 The doctor may still be charged under s.2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961 LW862: Death and Dying voluntary euthanasia. In these situations the patient is unable or does not wish to perform the final act himself and instead requests that the doctor personally administers the lethal dose. Although medically practised active euthanasia has been legal in the Netherlands since November 2000,21 the practise is illegal under English law, a position that was confirmed by Lord Mustill in Bland in which his Lordship stated that ‘the fact that the doctor’s motives are kindly...makes no difference in law. It is the intent to kill or cause grievous bodily harm which constitutes the mens rea of murder.’22 Furthermore, whilst Mason and Laurie argue that these two approaches, prima facie appear to be distinctive, it is not always easy to distinguish between active euthanasia and PAS in practice.23 Consequently, it is clear that some care needs to be taken when attempting to introduce any legislation that defines PAS as a separate, but lawful, entity. In addition, Meyers and Mason have identified several factual situations in which the distinction between PAS and euthanasia is ambiguous. For example, what is the position of a doctor who performs a venepuncture and holds the syringe full of barbiturates while the patient presses the plunger?24 Arguably, it can be said that the doctor is performing both PAS and active euthanasia. Consequently, as this situation clearly demonstrates, it is not always possible to draw a distinction between the two categories in certain circumstances. In spite of these difficulties, the courts are keen to perceive a distinction and hence, clearly categorise an activity as either PAS or an act of active euthanasia. This approach can be demonstrated by the American case of Vacco, in which the court held that ‘the distinction between assisting suicide and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment...is logical, widely recognised and endorsed by the medical profession and by legal tradition.’25 However, in spite of the legal semantics in that case, it is questionable whether there is any real difference between a doctor who accepts a patient’s refusal of medical treatment despite knowing that her decision will prove fatal and a request by a terminally ill patient for PAS. Consequently, one can only assume that the court’s approach in classifying the issue as a withdrawal of treatment, as opposed to assisting a suicide, represents an attempt to avoid making a decision that can be interpreted as supporting euthanasia.26 21 The Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act Airedale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] 1 All ER 821 at 980 23 J. K. Mason and G. Laurie, Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics, 7th Edition, Oxford, 2005, p.612 24 W. Meyers and J. K. Mason, Physician Assisted Suicide: A Second View from Mid-Atlantic, 28 Anglo-American Law Review 265, 1999, p.265-266 25 Vacco v Quill 117 S Ct 2293 (1997) 26 J. K. Mason and G. Laurie, Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics, 7th Edition, Oxford, 2005, p.613 22 LW862: Death and Dying Notwithstanding jurisprudence to the contrary, it is clear that ‘there is no bright dividing line’27 between assisted suicide and euthanasia. However, as Churchill and King note, these difficulties are often overlooked as most people prefer to address the subject in the simple terms of either the doctor leaving the pills for the patient to take or the administering of a lethal injection by a health care professional.28 Consequently, it can be argued that for the layman, the finer distinctions between PAS and active euthanasia are less important29 and therefore, one can assume that many terminally ill patients would potentially welcome the opportunity to opt for legally assisted dying if it were provided as a properly-regulated30 service in another Member State. Although it is clear that this simplistic approach overlooks the finer ethical considerations in respect of the issue, it can be argued that ‘in an era of expanding patient choice and well-founded fears about the potential excesses of medical technology,’ the opportunity to recognise PAS as a service under Article 49 EC ‘has the potential to offer relief and greater certainty to a group of patients who desperately need it.’31 However, as Article 50 EC states that certain provisos must be adhered to before EC law will recognise something as a service, it is necessary to consider whether a system of PAS based on the Swiss model could be adopted in another EU Member State for the purposes of Article 49 EC. (B) Introducing the System of PAS in Switzerland Contrary to many other European jurisdictions, assisted suicide is not per se illegal in Switzerland. Since January 1 1942, Article 115 of the Swiss Penal Code has stated that it is not unlawful to assist another individual to commit suicide.32 Although prima face, this approach appears quite liberal in comparison to English law, there are several notable caveats: (1) Firstly, Swiss law is clear that the final decisive gesture i.e. taking the pills, swallowing the poison, pulling the trigger, must be under the control of the victim otherwise the act would be classified as murder as opposed to assisted suicide33 27 Ibid, p.612 L. R. Churchill and N. M. P. King, Physician Assisted Suicide, Euthanasia, or Withdrawal of Treatment, 315 British Medical Journal 137, 1997, p.137-138 29 J. K. Mason and G. Laurie, Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics, 7th Edition, Oxford, 2005, p.613 30 I.e. with sufficient safeguards – such as two the approval of two doctors, witnesses, etc 31 H. Biggs, The Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill 2004: Will English Law Soon Allow Patients the Choice to Die? 12 European Journal of Health Law 43, 2005, p.53 32 O. Guillod and A. Schmidt, Assisted Suicide Under Swiss Law, 12 European Journal of Health Law 25, 2005, p.30 33 Ibid 28 LW862: Death and Dying (2) Secondly, whilst the Penal Code allows an individual to assist another person to commit suicide, it is illegal to encourage someone to commit suicide. (3) Thirdly, any assistance must be in the form of a selfless act and such help cannot be given in order to satisfy any personal interest whether it be financial, professional or affective.34 Providing that these criteria are adhered to, it is perfectly legal in Switzerland to assist another in their own suicide. However, as Guilod and Schmidt argue, although, prima facie, Article 115 is ‘a criminal provision, and therefore cannot create a right to assisted suicide,’ this has not prevented the establishment of clinics such as Dignitas that allow for people to come to Switzerland to be helped in committing suicide.35 Furthermore, whilst the organised practice of assisted suicide is perfectly legal in Switzerland, the rise in death tourism has been severely criticised and there have been calls to limit the application of Article 115 to those permanently residing in the country.36 Dignitas was founded as an independent organisation37 on May 17 1998 by Ludwig Minelli, a Swiss lawyer who had considerable experience in working with EXIT; a Swiss organisation that specialises in right to die issues.38 The first assisted suicide was performed without any legal challenge on October 27 1998 at the, then newly established, Dignitas Clinic in Zurich.39 Initially, the right to PAS was only available for Swiss nationals, however this position was modified in September 1999 when for the first time, a terminally ill German national was allowed to travel to Zurich for assisted suicide.40 Following a consultation with Meinrad Schär, Professor of Social and Preventive Medicine at Zurich University, it was agreed that those who travel to Dignitas seeking assisted suicide would be prescribed Pentobarbital of Sodium by a Swiss physician.41 The medication is described by Minelli as ‘very potent’ and is only prescribed after a comprehensive examination of the patient’s medical records and an extensive consultation with a doctor. The Pentobarbital is usually given in doses exceeding four grams which is guaranteed to secure ‘a deep coma... respiratory arrest’42 and hence, the patient’s death. 34 Ibid Ibid, p.31 36 Ibid, p.32 37 Dignitas is not part of the Healthcare system provided by the Swiss Government 38 There are two organisations, both of which are called EXIT. One is based in Geneva (for French speaking Cantons) whilst the other is based in Zurich (for German speaking Cantons) 39 L. Minelli, DIGNITAS in Switzerland – its philosophy, the legal situation, actual problems and possibilities for Britons who wish to end their lives, Friends at the End (FATE), London Meeting, December 1 2007, p.4 40 This stance is in contrast to EXIT which argues that only Swiss residents should be allowed the right to assisted suicide 41 Providing several key steps are followed, see below. 42 L. Minelli, DIGNITAS in Switzerland – its philosophy, the legal situation, actual problems and possibilities for Britons who wish to end their lives, Friends at the End (FATE), London Meeting, December 1 2007, p.5 35 LW862: Death and Dying Although Dignitas allows terminally ill patients from foreign jurisdictions to seek PAS in Switzerland, it is questionable whether a similar system operated in an EU Member State could constitute a ‘service’ under Articles 49 and 50 of the European Community Treaty. Consequently, in order to address this issue, the author will now consider the procedure used at Dignitas in light of the ECJ case-law on the freedom to provide cross border services between Member States. (C) Could the Swiss system be adopted as the model for the purposes of Article 49 EC? Article 49 EC, which sets out the freedom to provide cross border services, is one of the four fundamental freedoms43 of the European Union and is a key component in the functioning of the Internal Market.44 Whilst the law on the free movement of services is very similar to that on the freedom of establishment, Craig and De Burca argue that the distinguishing feature of the freedom to provide services under Article 49 EC is that the activity in question is carried out for ‘a temporary period in a Member State,’ and that ‘either the provider or the recipient45 of the service is not established.’46 Although it is clear that the temporary nature of a service is a crucial requirement for EC Law, as will be discussed below, the jurisprudence of the ECJ has played an important role in developing the freedom to provide services under Articles 49 and 50 EC. (I) Fundamental Requirements: Temporary in Duration, Cross-Border Element, an Economic Foothold in a Member State and Remuneration The ECJ held in the Insurance Services47 case that if an individual or enterprise has a permanent base in a Member State, which can include a single office, that person (natural or legal) will not be able to claim a right under the Treaty to provide a service. However, the potentially far reaching implications of this approach have since been clarified by the recent decision in Gebhard.48 In that case, the ECJ re-examined its previous jurisprudence and accepted that the provision of a service did not cease to be temporary in nature49 merely because the provider requires certain infrastructure, such as an office or specific medical facilities, in order to perform the service. Consequently, it is clear that the provision of a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC ultimately depends on whether 43 The others being the free movement of goods (Articles 28-31 EC), the free movement of workers (Article 39 EC) and the freedom of establishment (Article 43 EC) 44 European Commission: The EU Single Market http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/services/principles_en.htm 45 I.e. the terminally ill patient who wishes to obtain PAS 46 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford 2007, p.813 47 Case 205/84 Commission v Germany [1986] ECR 3775, para 21 48 Case C-55/94 Gebhard v Consiglio dell’Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano [1995] ECR I-4165, para 27 49 And therefore outside the Scope of Article 49 EC LW862: Death and Dying the activity in question is carried out on a temporary rather than permanent basis in a Member State.50 Aside from insisting that the activity is pursued on a temporary basis, Article 49 EC also states that the right to provide services under EC Law requires an individual or undertaking to be established within a Member State of the Community. Additionally, in FKP Scorpio51 the ECJ has recently confirmed that in those situations where it is an individual (as opposed to an enterprise) that is seeking to provide a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC, it is obligatory that such persons are also in possession of a nationality of a Member State. Moreover, once the person in question (natural or legal) is established in the Community, he must also have an ‘economic foothold’ within a Member State52 from which to provide temporary services. Furthermore, in demonstrating that he has a ‘real and continuous link’53 with the economy of a Member State;54 a natural or legal person must also satisfy the requirements of Article 50 EC which states that any proposed service should be commercial in nature and provided for remuneration.55 Can any of these initial fundamental requirements be applied to a Dignitas-type model of PAS? Firstly, it is clear that in order to satisfy the requirement that the service provider has an ‘economic foothold’ within the Community, any PAS service would have to be operated from within a Member State of the EU56 and any recipient of that service would need to be a national of a different57 Member State.58 Secondly, although the ECJ held in Gebhard that the existence of an office or consulting room does not automatically disbar a legal or natural person from claiming a right to provide services under the EC Treaty, it can be argued that as the PAS provider would appear to be pursuing the activity in an EU Member State on a permanent basis, the provider would prima facie, be covered by the Treaty provisions on establishment. However, as Craig and De Burca have suggested, the crucial distinction between freedom to provide services and freedom of establishment is that ‘the provider or the recipient...is not established’59 in a Member State of the Community. Consequently, it can be argued that as the terminally ill patient seeking PAS in another 50 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford 2007, p.815 Case C-290/04 FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH v Finanzamt Hamburg-Eimsbüttel [2006] ECR I-9461 52 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford 2007, p.814 53 Ibid 54 Case C-452/04 Fidium Finanz v Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht [2006] ECR I-9521 55 Although in light of recent case law of the ECJ in light of cross-border health care, this requirement is now questionable see Case C-372/04 Watts v Bedford Primary Care Trust [2006] ECR I-4325 56 As opposed to an European Economic Area Country such as Switzerland 57 For a cross-border element to apply, it is clear that there needs to be a movement between Member States, otherwise the scenario is classified as a ‘Wholly Internal Situation’ and consequently, the EC Treaty Provisions will not apply – see Case 52/97 Procureur du Roi v Debauve [1980] ECR 883 58 As Switzerland is not a Member State of the EU – it is arguable that this requirement is unique to EC Law 59 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford 2007, p.813 51 LW862: Death and Dying Member State is not established in that State, the Dignitas-type organisation would be providing the activity to the patient on a temporary basis and hence, the provider would be covered by Articles 49 and 50 of the Treaty. Furthermore, although an organisation offering PAS would require an ‘economic foothold’ in a Member State of the Community, it is questionable whether the activity of PAS itself could be classified as a ‘service’ for the purposes of the Treaty. In Luisi and Carbone60 the ECJ held that the provision of medical treatment can be classified under Article 50(d) EC as ‘activities of the professions.’ Therefore, as PAS at Dignitas involves an examination of a terminally ill patient’s medical records and several detailed consultations with a Swiss physician prior to the prescription of the Pentobarbital of Sodium,61 it is arguable that the procedure can be properly classified as an ‘activity of the professions’ and hence, satisfy the requirements of Article 50(d) EC. Moreover, in Gerates-Smits62 the ECJ expanded its previous approach in Luisi and held that not only do all medical activities fall within the scope of the Treaty, but EC Law does not distinguish between ‘care provided in a hospital environment and care provided outside such an environment.’63 Consequently, it is clear that even though Dignitas does not operate in a standard hospitalised environment,64 the organisation is still classified as providing medical care, and therefore services, for the purposes of EC Law. Whilst the ECJ has accepted that medical activities can fall within the scope of the Treaty, it is clear that a ‘service’ for the purpose of EC Law depends not only on an inter-state element, but also that the activity is provided for remuneration.65 Arguably, the system operated in Switzerland appears to satisfy these requirements. In order to have an assisted suicide at Dignitas the terminally ill patient must become a member of the organisation – which costs 200 CHF for an initial registration fee and 80 CHF for each subsequent year’s membership.66 Moreover, once all of the necessary steps have been adhered to and the patient is ready to take the Pentobarbital of Sodium, there is a final charge 60 Cases 286/82 and 26/83 Luisi and Carbone v Ministero del Tesoro [1984] ECR 377, para 16 L. Minelli, DIGNITAS in Switzerland – its philosophy, the legal situation, actual problems and possibilities for Britons who wish to end their lives, Friends at the End (FATE), London Meeting, December 1 2007, p.4-5 62 Case C-157/99 Gerates-Smits v Stichting Ziekenfonds, Peerbooms v Stichting CZ Group Zorgverzekeringen [2001] ECR I-5473 63 Geraets-Smits [2001] ECR I-5473 at para 53 64 Dignitas operates from a tower block in Zurich 65 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford 2007, p.818 66 L. Minelli, DIGNITAS in Switzerland – its philosophy, the legal situation, actual problems and possibilities for Britons who wish to end their lives, Friends at the End (FATE), London Meeting, December 1 2007, p.5. Arguably this satisfies the condition that some form of remuneration is needed as consideration for the service in question – see Case C-76/05 Schwarz and Gootjes-Schwarz v Finanazamt Bergisch Gladbach [2007] ECR I6849 at para 38 61 LW862: Death and Dying to pay for the assisted suicide itself and to cover any other arrangements that the patient may have made in the aftermath of his death.67 Furthermore, the fact that Dignitas is a non-profit organisation makes no difference to the remuneration requirements of Article 50 EC and the ECJ has ruled that such activities do not lose their economic nature. 68 Moreover, whilst it is a requirement that services under EC Law are provided for remuneration, the ECJ has taken a teleological approach in its interpretation of this proviso and stated in Bond van Adverteerdas that the remuneration did not have to come from the recipient of the service, provided there was some remuneration from another party.69 In respect of an EU-based service for PAS, this position would allow those terminally ill individuals who cannot afford to travel to institutions such as Dignitas the right to seek financial help from charities and relatives without worrying that such people would be potentially at risk from prosecution.70 Based on the discussion above, it is arguable that the provision of PAS in a Member State of the EU by a Dignitas-type organisation could prima facie be considered as a service under EC law. In classifying PAS as a service under the Treaty it is clear that terminally ill individuals would be afforded considerable rights under EC law to obtain this service in another Member State. The remainder of this paper will consider the rights that such individuals would have under Articles 49 and 50 EC and whether any restrictions imposed by Member States on PAS as a service could be justified. The Right to Receive Physician-Assisted Suicide as a Service Whilst the Treaty expressly allows for the freedom to provide services, it does not specifically mention the rights of the recipients of that service. This anomaly was finally rectified in Luisi and Carbone where the ECJ held that the ‘freedom to provide services includes the freedom, for the recipients of services, to go to another Member State in order to receive a service there, without being obstructed by restriction.’71 Therefore, it is clear that in order to provide services under EC Law 67 There is a charge of €4000 for preparation and suicide assistance only, and an increased charge of €7000 if the patient wishes Dignitas to take over family duties, funerals, doctor’s costs and official fees 68 Case C-70/95 Sodemare v Regione Lombardia [1997] ECR I-3395 69 Case 352/85 Bond van Adverteerdes v Netherlands [1988] ECR 2085 70 This is discussed in greater detail below, but based on the notion that EC Law takes precedent over conflicting domestic law; the right to free movement for services under EC Law could potentially trump domestic provisions such as the Suicide Act which make it an offence for individuals to assist another to commit suicide. 71 Luisi and Carbone [1984] ECR 377 at para 16 LW862: Death and Dying ‘the freedom for the recipient to move [is] the necessary corollary of the freedom for the provider;’ a position that has since been confirmed by the ECJ in subsequent cases.72 Furthermore, the ECJ held in Van Binsbergen73 that Article 49 EC confers vertical direct effect and accordingly, as the provisions of the Treaty Articles relating to the free movement of services are sufficiently clear, precise and unconditional; 74 they can be invoked and relied upon by individuals before national courts. Consequently, it can be argued that if a Member State of the Community began to provide PAS for the purposes of Articles 49 and 50 EC, then nationals from other Member States would be able to directly rely on the right of free movement provided by the Treaty to travel to that Member State and receive the service of assisted dying.75 Arguably, this right would prove particularly problematic in England where those individuals who have accompanied the terminally ill to receive PAS in another Member State would potentially be at risk from prosecution under s.2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961. Although de Cruz argues that the decision of Hedley J not to recommend prosecution in Re Z76 for the husband who made arrangements for his wife to seek assisted dying in Switzerland represents a ‘watershed’ in English law and suggests that the Suicide Act ‘is on its last legs,’77 it is clear that the Act has not been repealed and in theory, remains good law. Furthermore, s.2(4) of the Suicide Act provides that the decision to prosecute an individual under s.2(1) for aiding and abetting a suicide remains the prerogative of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), and it can be suggested that in Re Z the DPP did not think it appropriate to exercise this power in that particular case.78 Moreover, whilst Hedley J believed that the Suicide Act represents a situation where Parliament recognised that ‘although an act might be criminal, it was not always in the public interest to prosecute in respect of it,’79 it is questionable whether the same approach would be applied to an EC legal right to PAS as a service in another Member State. Arguably, whilst only 100 Britons have been helped to die at 72 Most notably Case 186/87 Cowan v Le Trèsor Public [1989] ECR 195 Case 33/74 Van Binsbergen v Bestuur van de Bedrijsvereniging voor de Metaalnijverheid [1974] ECR 1299 74 The original criteria for direct effect of Treaty Articles as laid down by the ECJ in Case 26/62 NV Algemene Transporten Expeditie Onderneming van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen [1963] ECR 1 para 12-13 75 P. Pescatore, The Doctrine of ‘Direct Effect’: An Infant Disease of Community Law, 8 European Law Review 155, p.158, 1983 76 In Re Z (Local Authority: Duty) [2004] EWHC 2817 (Fam) 77 P. De Cruz, The Terminally Ill Adult Seeking Assisted Suicide Abroad: The Extent of a Duty Owed by a Local Authority, 13(2) Medical Law Review 257, 2005, p.261 78 The same can be said about Daniel James – on 9 December 2008 Keir Starmar QC, Director of Public Prosecutions, announced that it was not in the public interest to pursue a prosecution against James’ parents under s.2(1) of the Suicide Act for taking their son to Dignitas in September 2008; No Charges over Assisted Suicide, BBC News, 9 December 2008 79 [2004] EWHC 2817 (Fam) at para 14 73 LW862: Death and Dying Dignitas, it can be suggested that the ‘spectre’ of prosecution under the Suicide Act has deterred many others from seeking PAS abroad.80 Notwithstanding the English legal position, it is clear that Article 49 EC confers vertical direct effect, and therefore, allows an individual to rely on the freedom to receive services in another Member State. Consequently, it is arguable that a terminally ill person could potentially challenge s.2(1) of the Suicide Act as in contravention of his right to free movement to receive services under the Treaty. Many terminally ill individuals are unable to physically travel abroad to receive PAS and consequently, require help from relatives or carers in seeking assisted dying. However, as discussed above it is clear that such individuals are at risk from prosecution upon their return to the UK. The ECJ held in Costa that ‘the Treaty carries with it a permanent limitation of [Member States’] sovereign rights, against which a subsequent unilateral act incompatible with the concept of the Community cannot prevail,’81 and therefore, in situations where EC Law and domestic law conflict, the domestic law should be set aside. Accordingly, as the provisions of the Suicide Act would prima facie be in conflict with a terminally ill person’s right to PAS as a service under Articles 49 and 50 EC, it can be argued that the principle of supremacy of EC Law applies and hence, the Suicide Act should be disapplied.82 It is clear from the ECJ decision in Internationale Handelsgesellschaft mbH83 that the legal status of a conflicting national measure is irrelevant to whether Community law should take precedence, and in theory, even fundamental rules of national constitutional law are to be disapplied. Similarly, even though the Suicide Act predates the UK’s entry into the Community, the ECJ held in Simmenthal84 that the doctrine of supremacy applies regardless of whether the national law pre-dates or postdates the relevant Community Law and that the doctrine must be universally applied by all national courts within the Member State. Although Lord Bridge appeared to accept the supremacy of EC Law in Factortame by stating ‘in the protection of rights under Community law, national courts must not be inhibited by rules of national law,’85 in the later case of Thoburn, Laws LJ warned that if a ‘European measure was seen to be repugnant to a fundamental...right guaranteed by the law of 80 Indeed this is the issue with Debbie Purdy who has sought a declaration that her husband will not be prosecuted under the Act – see R (on the Application of Purdy) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2008] EWHC 2565 81 Case 6/64 Flamino Costa v ENEL [1964] ECR 585 at p.593 82 K. Lenaerts and T. Corthaurt, Of Birds and Hedges: The Role of Primacy in Invoking Norms of EU Law, 31 European Law Review 287, 2006, p.290-291 83 Case 11/70 International Handelsgesellschaft mbH v Einfuhr-und Vorarsstelle für Getreide und Futtermittel [1970] ECR 1125 84 Case 106/77 Amministrazione della Finanze dello Stato v Simmenthal SpA [1978] ECR 629 85 Factortame Ltd v Secretary of State for Transport (No 2) [1991] 1 AC 603 at 658 LW862: Death and Dying England.’ 86 Consequently, it remains unclear whether the English courts would disapply the Suicide Act as being in contravention of a terminally ill person’s rights and recognise the supremacy of EC law in respect of an individual’s right to receive PAS as a service under Article 49 of the Treaty. A Member State offering PAS as a service for the purpose of Articles 49 and 50 of the Treaty would afford terminally ill patients the freedom of movement to receive the service in that State. Furthermore, the direct vertical effect of Article 49 EC has the potential to expand the rights of those individuals who need assistance in seeking PAS abroad and it is questionable whether English law could continue to deny the terminally ill the right to free movement by prosecuting carers and relatives under the Suicide Act. However, it is inevitable that the supremacy of EC law on this matter would be controversial and it is unclear whether the English courts would accede to previous ECJ jurisprudence on the issue. 87 Despite these problems, it is arguable that the provision of PAS as a service could be restricted by a Member State under the agreed exceptions in Article 55 EC or the list of open-ended ‘imperative requirements’ that have been developed from the jurisprudence of the ECJ. Restrictions on Physician-Assisted Suicide as a Service As Craig and De Burca note, some Member States may have good reasons for wanting to restrict the provision of certain services.88 Arguably, one of the most contentious issues concerns ‘immoral’ services, which are lawful in certain Member States but not in others. Consequently, it is of particular importance whether these contentious activities, the legality of which Member States cannot agree upon, can be classified as ‘services’ for the purposes of Community law.89 Although the ECJ has not yet had to consider whether PAS can constitute a service under Community Law, it is arguable that the issue of abortion rights represents a similar problem. In Grogan, the ECJ had to determine whether abortion was a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC and if a ban by the Irish Government on the provision of information relating to abortion clinics in the United Kingdom constituted a violation of Community law. Whilst the ECJ was keen to ensure that it did not express an opinion as to whether abortion was immoral,90 the Court ruled that it would not ‘substitute its assessment for that of the legislature in those Member States where the activities are 86 Thoburn v Sunderland City Council [2003] QB 151 at para 69 P. Craig, ‘Britain in the European Union,’ in J. Jowell and D. Oliver (eds), The Changing Constitution, 6th Edition, Oxford, 2007, Chapter 4 88 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford, 2007, p.823 89 Craig and De Burca, p.823 90 B. Wilkinson, Abortion, the Irish Constitution and the EEC, Public Law, Spring 1992, p.26 87 LW862: Death and Dying practised legally,’91 and dismissed the application on the grounds that there was not a sufficient link to EC Law.92 This position of deferring to the Member States was continued in the later cases of Schindler93 and Jany,94 and consequently, it can be argued that so long as an activity is lawful in some Member States95 and the other conditions laid down in Articles 49 and 50 of the Treaty are adhered to;96 the activity can be classified as a service for the purpose of Community law. Based on the ECJ’s approach in Grogan, it is arguable that a Dignats-type model of PAS could constitute a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC. However, it is clear that if a Member State wishes to restrict such a service, it must do so under the Treaty exceptions listed in Article 55 EC or under the ECJ approved list of imperative requirements. In respect of Article 55 EC, it is not surprising, as with all Treaty exceptions to the fundamental freedoms, that the ECJ has construed this Article narrowly, strictly and exhaustively.97 Furthermore, it is clear that any limits imposed on the operation of a service by a Member State will be closely scrutinised by the ECJ to ‘ensure that the defence pleaded is warranted on the facts of the case,’ and that any limitations are proportionate and ‘the least restrictive’’98 option. Moreover, it was accepted in Van der Veldt99 that the burden of proof in justifying any restrictions on the freedoms provided by the Treaty rests with the Member State. In respect of providing the service of PAS in a Member State, it is arguable that the public policy exception under Article 55 of the Treaty would be most applicable. Arguably, in States such as Germany100 where there is a Constitutional Right to human dignity and an established legal tradition for preserving live at any cost,101 it can be argued that there would be strong public policy reasons for restricting the provision of some services such as PAS. Consequently, prima facie it can be 91 Case C-159/90 SUPC v Grogan [1991] ECR I-4685 The main issue was that there was no payment for the provision of information and the case focused more on that aspect than whether abortion was a service per se 93 Case C-272/92 HM Customs and Excise v Schindler [1994] ECR I-1039 94 Case-C-268/99 Jany v Staatssecretaris van Justitie [2001] ECR I-8615 95 Although Craig and De Burca question whether one Member State would be sufficient – p.824 96 See the discussion above 97 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford, 2007, p.696 98 Ibid 99 Case C-17/93 Openbaar Ministerie v Van der Veldt [1994] ECR I-3537 100 Although Dignitas has opened a clinic in Hanover, Lower Saxony, the decision has been extremely controversial and is currently under threat from a legal challenge by the Justice Minister of Lower Saxony and the Federal Health Ministry of Germany. If these motions are successful, it is likely that the clinic will be forced to close – see A. Tuffs, Assisted Suicide Organisation opens branch in Germany, 331 British Medical Journal 7523, p.984, 29 October 2005 101 However, it has been revealed in a recent survey carried out by Der Spiegel that 40% of German Doctors would be prepared to carry out PAS and would like the current German law to be changed, A. Tuffs, A Third of German Doctors Would Like the Law on Assisted Suicide to be Changed, 337 British Medical Journal 2814, 2 December 2008 92 LW862: Death and Dying suggested that in light of the ECJ’s decision in Omega,102 any derogation from Article 49 EC on the grounds that allowing PAS a service would contravene such a fundamental right of national constitutional law could potentially be justified as a proportionate and acceptable measure. However, although the ECJ was prepared to recognise in Omega that the protection of human life and dignity could form part of the general principles of EC Law, it is clear that any attempt to restrict PAS as a service under the grounds of public policy is dependent upon several Member States103 adopting a similar position.104 Furthermore, whilst it can be argued that a significant number of Member States would need to adopt a similar position before a PAS service could be banned in an individual State under the public policy exception of Article 55 EC, the ECJ has also held that the risk of civil disturbances105 in those states which would allow PAS cannot be used as a justification for restricting such a service. In Cullet,106 Advocate General Van Thematt107 held that the risk of civil disturbances cannot be used as a justification for encroachment upon the freedoms guaranteed by the Treaty and argued that such problems should be dealt with effectively by the authorities within a Member State, rather than on the grounds of public policy.108 Consequently, it is clear that if a State such as the Netherlands109 wishes to provide a Dignitas-type system of PAS as a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC, any limitation on the service for public policy reasons under Article 55 EC must be proportionate and not used as a means to advance what amounts to an entirely different reason110 for the restriction.111 Although the ECJ has treated the list of exceptions in Article 55 of the Treaty as exhaustive, the Court has developed a justificatory test to examine whether national measures liable to hinder or restrict the freedom to provide services under Article 49 EC can be upheld. The test was first laid down in 102 Case C-36/02 Omega Spielhallen-und Automatenaufstellungs-GmbH v Oberbürgerjeisterin der Biundesstadt Bonn [2004] ECR I-9609 103 Arguably, the need for several Member States to enact similar restrictions reflects the initial proportionality concerns of the ECJ in Omega 104 Case C-245/01 RTL Television GmbH v Niedersächsische Landesmedienanstalt für privaten Rundfunk [2003] ECR I-12489 105 This would be a particular problem in Member States such as Spain, Poland and the Republic of Ireland that have a strong Catholic influence – see N. Wood, Pro-Euthanasia Poll Misleading, Care Not Killing, 24 January 2007 106 Case 231/83 Cullet v Centre Leclerc [1985] ECR 305 107 Although Cullet concerned a public policy argument for the restriction of the free movement of goods under Article 29 EC, it can be implied from the Advocate General’s reasoning that he intended his opinion to apply to all four freedoms guaranteed by the EC Treaty 108 Cullet v Centre Leclerc [1985] 2 CMLR 524, p.534 109 The Netherlands already allows PAS, albeit not as a service for the purposes of EC Law. Luxembourg has recently become the third EU Member State to permit PAS. 110 I.e. the risk of civil disobedience 111 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford, 2007, p.698 LW862: Death and Dying Van Binsbergen and it is clear that for a national restriction on the freedom to provide services to be upheld, the measure must be proportionate and applied in a non-discriminatory manner. It is arguable that the ECJ’s approach in Müller-Fauré,112 where the Court held that that the objective of maintaining a high-quality, balanced medical and hospital service open to all, could potentially be classified as an objective justification for restricting the provision of PAS a service in a Member State. However, as the author has argued that a Dignitas-type model should be used, it is questionable whether this objective justification would apply. Whilst the ECJ held In Müller-Fauré that restrictive measures could be justified in terms of hospital treatment, the Court argued that this was not the case in terms of non-hospital measures. As Dignitas does not operate within the medical care system of Switzerland, and hence cannot be classified as a hospital service, it is unclear whether an objective justification based on national healthcare concerns would be valid. Finally, it is arguable that a Member State which offers PAS to its own citizens would not be able to impose additional excessive penalties to those from another State on the grounds that cross-border PAS would upset the financial balance of the social security system. Such a measure would be discriminatory and as the ECJ held in Leichtle,113 this approach applies even to non-standard medical treatments such as spa therapies. Arguably, a Member State that wishes to restrict the provision of a PAS service must do so either under one of the agreed Treaty exceptions or under the objective justification test developed by the ECJ. Furthermore, it is clear that any limitation must be proportionate, non-discriminatory and genuine.114 Whilst there are clear public policy reasons for denying PAS in some States, it is arguable that in others such as the Benelux countries, the issue is far less contentious115 and consequently, it is unlikely that there would be an EU wide ban or the introduction of harmonization measures on such a service.116 Conclusion: Deus Ex Machina? This paper has considered whether a Dignitas-type model of PAS could be classified as a service for the purposes of Article 49 EC. It is clear from the discussion above that a system which is properly 112 Case C-385/99 Müller-Fauré [2003] ECR I-4509 Case C-8/02 Leichtlie [2004] ECR I-2641 114 A. Biondi, Free Trade, a mountain and the right to protest: European economic freedoms and fundamental rights, 1 European Human Rights Law Review 51, p.53-55, 2004 115 G. Laurie, Physician-Assisted Suicide in Europe: Some Lessons and Trends, 12 European Journal of Healthcare Law 5, 2005, p.5-6 116 This is reflected by the recent Directive 2006/123 on services in the internal market which deliberately excludes healthcare from its ambit 113 LW862: Death and Dying regulated, operated by medical professionals and provided in return for remuneration would satisfy the requirements of the EC Treaty. Although it is unlikely that any Member States would offer a PAS service in the foreseeable future, it is arguable that the supremacy of EC Law could overrule any restrictions imposed by English law in allowing an individual to exercise their right under Community Law to seek assisted dying in another EU State. Furthermore, whilst there are permitted exceptions to the freedom to provide a service, the ECJ has continually stated that any restrictions to Article 49 EC must be non-discriminatory and proportionate. Moreover, in distinguishing between hospital and non-hospital services, the Court has held that any restrictive measures imposed by Member States are more justifiable in respect of the former than the latter.117 Consequently, as a Dignitas-type model would operate outside the hospital services of a Member State, it is arguable that the ECJ has set a considerably high threshold for a State to achieve before PAS could be prohibited as a service within its jurisdiction. Clearly, it is arguable that the freedom to receive PAS as a service in another Member State of the Union could provide a solution to many of the difficulties currently faced by UK nationals who wish to seek assisted suicide abroad. Case List English Case Law: Airedale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] 1 All ER 821 Factortame Ltd v Secretary of State for Transport (No 2) [1991] 1 AC 603 In Re Z (Local Authority: Duty) [2004] EWHC 2817 (Fam) R (on the Application of Purdy) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2008] EWHC 2565 R v Woolin [1999] 1 AC 82 Thoburn v Sunderland City Council [2003] QB 151 Case Law of the European Court of Justice Case 106/77 Amministrazione della Finanze dello Stato v Simmenthal SpA [1978] ECR 629 Case 352/85 Bond van Adverteerdes v Netherlands [1988] ECR 2085 Case 205/84 Commission v Germany [1986] ECR 3775 Case 186/87 Cowan v Le Trèsor Public [1989] ECR 195 Case 231/83 Cullet v Centre Leclerc [1985] ECR 305 Case C-452/04 Fidium Finanz v Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht [2006] ECR I-9521 Case C-290/04 FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH v Finanzamt Hamburg-Eimsbüttel [2006] ECR I-9461 Case 6/64 Flamino Costa v ENEL [1964] ECR 585 Case C-55/94 Gebhard v Consiglio dell’Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano [1995] ECR I4165 Case C-157/99 Gerates-Smits v Stichting Ziekenfonds, Peerbooms v Stichting CZ Group Zorgverzekeringen [2001] ECR I-5473 Case C-272/92 HM Customs and Excise v Schindler [1994] ECR I-1039 117 P. Craig and G. De Burca, EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, Oxford, 2007, p.830 LW862: Death and Dying Case 11/70 International Handelsgesellschaft mbH v Einfuhr-und Vorarsstelle für Getreide und Futtermittel [1970] ECR 1125 Case-C-268/99 Jany v Staatssecretaris van Justitie [2001] ECR I-8615 Case C-8/02 Leichtlie [2004] ECR I-2641 Cases 286/82 and 26/83 Luisi and Carbone v Ministero del Tesoro [1984] ECR 377 Case C-385/99 Müller-Fauré [2003] ECR I-4509 Case 26/62 NV Algemene Transporten Expeditie Onderneming van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen [1963] ECR 1 Case C-17/93 Openbaar Ministerie v Van der Veldt [1994] ECR I-3537 Case C-36/02 Omega Spielhallen-und Automatenaufstellungs-GmbH v Oberbürgerjeisterin der Biundesstadt Bonn [2004] ECR I-9609 Case 52/97 Procureur du Roi v Debauve [1980] ECR 883 Case C-245/01 RTL Television GmbH v Niedersächsische Landesmedienanstalt für privaten Rundfunk [2003] ECR I-12489 Case C-76/05 Schwarz and Gootjes-Schwarz v Finanazamt Bergisch Gladbach [2007] ECR I-6849 Case C-70/95 Sodemare v Regione Lombardia [1997] ECR I-3395 Case C-159/90 SUPC v Grogan [1991] ECR I-4685 Case 33/74 Van Binsbergen v Bestuur van de Bedrijsvereniging voor de Metaalnijverheid [1974] ECR 1299 Case C-372/04 Watts v Bedford Primary Care Trust [2006] ECR I-4325 Case Law from Other Jurisdictions Vacco v Quill 117 S Ct 2293 (1997) Bibliography Barnard, C. The Substantive Law of the EU: The Four Freedoms, Oxford, 2004 BBC News, 29 October 2008 BBC News, 9 December 2008 Biggs, H. The Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill 2004: Will English Law Soon Allow Patients the Choice to Die? 12 European Journal of Health Law 43, 2005 Biondi , A. Free Trade, a mountain and the right to protest: European economic freedoms and fundamental rights, 1 European Human Rights Law Review 51, 2004 Churchill, L. and King, N. Physician Assisted Suicide, Euthanasia, or Withdrawal of Treatment, 315 British Medical Journal 137, 1997 Craig, P. ‘Britain in the European Union,’ in J. Jowell and D. Oliver (eds), The Changing Constitution, 6th Edition, Oxford, 2007, Chapter 4 Craig, P. and De Burca, G. EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials, 4th Edition, Oxford, 2007 De Cruz, P. The terminally ill adult seeking assisted suicide abroad: the extent of the duty owed by a local authority, 13(2) Medical Law Review 257, 2005 Freeman, M. Denying death its dominion: thoughts on the Dianne Pretty case, 10(3) Medical Law Review 245, 2002 LW862: Death and Dying Gibb, F. Swiss Clinic Has Helped 100 Britons to die, The Times, October 2 2008 Guillod, O. and Schmidt, A. Assisted Suicide under Swiss Law, 12 European Journal of Health Law 25, 2005 Hatzopoulous, V. and Do, T. The Case Law of the ECJ Concerning the Free Provisions of Services 20002005, 43 Common Market Law Review 923, 2006 Laurie, G. Physician-Assisted Suicide in Europe: Some Lessons and Trends, 12 European Journal of Healthcare Law 5, 2005, p.5-6 Leidig, M. and Sherwell, P. Swiss to crack down on suicide tourism, Daily Telegraph, 14 March 2004 Lenaerts, K. and Corthaurt, T. Of Birds and Hedges: The Role of Primacy in Invoking Norms of EU Law, 31 European Law Review 287, 2006 Martinsen, D. Towards and Internal Health Market with the European Court of Justice, 28 West European Politics 1035, 2005 Mason, J. and Laurie, G. Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical Ethics, 7th Edition, Oxford, 2005 Meyers, W. and Mason, J. Physician Assisted Suicide: A Second View from Mid-Atlantic, 28 AngloAmerican Law Review 265, 1999 Minelli, L. DIGNITAS in Switzerland – its philosophy, the legal situation, actual problems, and possibilities for Britons who wish to end their lives, Friends at the End (FATE), London Meeting, December 1 2007 Pedain, A. Assisted Suicide and Personal Autonomy, 61(3) Cambridge Law Journal 511, 2002 Pescatore, P. The Doctrine of ‘Direct Effect’: An Infant Disease of Community Law, 8 European Law Review 155, 1983 Schwarze, K. Legal Restrictions on Physician Assisted Suicide, 12 European Journal of Health Law 11, 2005 Snell, J. Goods and Services in EC Law, Oxford, 2002 Tuffs, A. Assisted Suicide Organisation opens branch in Germany, 331 British Medical Journal 7523, p.984, 29 October 2005 Tuffs, A. A Third of German Doctors Would like the Law on Assisted Suicide to be Changed, 337 British Medical Journal 2814, 2 December 2008 Tur, R. Legislative technique and human rights: the sad case of assisted suicide, Criminal Law Review 3, January 2003 Van Nuffel, P. Patients’ Free Movement Rights and Cross-border Access to Health Care, 12 Maastricht Journal 235, 2005 Wilkinson, B. Abortion, the Irish Constitution and the EEC, Public Law, Spring 1992 LW862: Death and Dying Wood, N. Pro-Euthanasia Poll Misleading, Care Not Killing, 24 January 2007 <carenotkilling.org.uk> accessed 4 December 2008