Occupational Therapy in acute care - St. Luke's Hospital and Health

advertisement

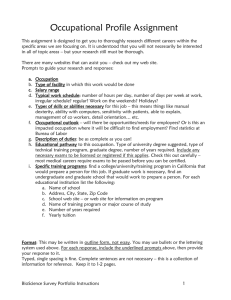

St. Luke’s University Health Network Neuroscience Symposium 2015 DeSales University March 7, 2015 Dr. Julia Glenn, OTD, OTR/L, C-GCM Objectives Background and challenges of acute care today Literature review Summary of findings- New opportunities! Conceptual models The Future of Occupational Therapy Introduction US: 700,000 new or recurrent stroke, 1 every 45 seconds 1.25 men>women ½ all acute neurological hospitalizations 50% are hemiparetic, 12-19% are aphasic, 35% suffer from depression, 26% require nursing home care, 30% cannot walk, and 24-53% report complete or dependent assist for ADLS Health Care Reform Focus on client centered, occupation based interventions to: Promote engagement Prevent psychosocial complications Background Occupational therapy and the paradigm shift towards holism Introduces an encompassing definition for OT services Increasing elderly population in the future Health Care Reform Less insurance denials in acute care/rehab Need for evidence based practice to justify occupation 4 Implications of the Changes in Healthcare in Acute Care Shorter length of stay. Higher demands on productivity. Less staff to treat increase case loads. New rules and regulations (60%,40% rule) for the coverage of acute rehab services are changing the types of patients OTs treat Rehab hospitals will be treating more medically and psychosocially complex patients 5 Occupational Therapy and Acute Care Administrative transformations Decrease in staffing to be cost effective=lack of communication and pursuit of fast paced discharges Implementation of program improvements for care Medicare/Medicaid Services will pay health systems based on quality care Academic Health Centers need to explore new approaches to demarcate & integrate holism Sounds like a need for occupation based practice, doesn’t it? 6 Objectives Background and challenges of acute care today Literature review Summary of findings- New opportunities! Conceptual models The Future of Occupational Therapy Literature Review: Occupation and Acute Care Occupation and Acute Care: Oxymoron? Reductionistic, biomechanical, medical model UB ADLs, UE ROM/MMT, and grooming Impaired our vision- disregard occupation Pilot study: perceptions of role in acute care Most studies relate to effectiveness of intervention strategies Others focus on mobility and deconditioning w/o occupation Psychological well being- rarely addressed 8 PICO Question What are the most effective intervention strategies for improving function in adults diagnosed with CVA and depression? Can occupational engagement improve overall affect and mood in adults diagnosed with CVA and demonstrating signs and symptoms of depression? What are the effects of occupational engagement on improving functional independence and overall affect/mood in adults diagnosed with CVA and demonstrating signs and symptoms of depression? Five Themes Emerged… 1) Participation 2) Occupational engagement 3) Social support 4) Quality of life 5) Physical therapeutic exercise Participation 5/15 articles (4 level III, 1 level I) 5 were quantitative: 3 cross sectionals, single case design, 1 meta-analytic systematic review Rehab should focus on participation in IADLS and leisure activities Participation in meaningful activities while focusing on depression can improve mood and life satisfaction Couple psychotherapeutic interventions with physical engagement to decrease restricted participation Participation Continued… Initially focus on economic sufficiencies, independence and social/environmental participation, then later focus on leisure activities and occupational participation Be sensitive to MCI’s impact on participation and acknowledge these challenges and focus on returning to participation in all activities Further research needed on: Occupation based interventions improving I/ADL, and role participation The impact habits and contextual/environmental influence, and strategy training vs task-specific training have on enabling occupation based participation Occupational Engagement 2/15 articles (2 level V’s, 2 qualitative phenomenologies) Combine re-engagement patterns of old occupations as well as exploring new occupations is proposed to manage s/s depression Maximize re-integration or facilitating adaptation/accommodation for occupation based engagement Little research is available that explores the impact of emotional changes on rehabilitation or effective treatment approaches to manage post stroke emotional changes Existing research suggests feelings of incompetency or incapacity with difficulty with re-engaging in old occupations -> eliciting emotional changes Further research is suggested to be conducted to investigate the impact of the person-centered process on improving social participation and well-being Social Support 2/15 articles (2 quantitative, 1 cross sectional, 1 level III, 1 systematic literature review, 1 level I) Time use satisfaction levels are positively or negatively influenced by the presence or lack of social support Clinically, screening for depression and promoting frequent, immediate, and intense positive social support has a definite impact on improve quality of life and remediating psychiatric distress Quality of Life 4/15 articles (4 quantitative, 4 level III, 3 cross sectionals, 1 single case design) Address psychological distress and stressors in acute phases is important for improving QOL Fatigue and motor function were ID’d as important unmet demands that impede quality of life Depression is often unrecognized and affects activity participation and fatigue that affects QOL and life satisfaction Quality of Life Continued… Healthcare does not manage, address, or meet LTC needs of survivors OR survivors’ perspectives of demands vs expectations are ? Reasonable Depression and emotional changes have a larger impact in the early phases (12mo) of recovery and impact QOL Improving social support and reducing emotional problems early on enhances QOL Even MCI and mild emotional dysfunctions can have a LT effect on QOL if left unmanaged Physical Therapeutic Exercise 2/15 articles (2 quantitative, 1 pilot study case control design, 1 cohort design, 2 level III) Participants with and without cognitive impairments/depressive symptoms improved over time w/ physical therapeutic exercise and repetitive task practice Therapeutic strength and exercise programming has a positive effect on depressive symptoms, mood, & QOL in subacute phases Depression does not limit gains in function or impairments attributable to exercise Objectives Background and challenges of acute care today Literature review Summary of findings- New opportunities! Conceptual models The Future of Occupational Therapy Summary of Findings None relate to latest PICO: In adult stroke survivors, do mood disorders and life dissatisfaction significantly impact functional participation and quality of life? 14/15 articles at an average of level III evidence with most certainty support that mood disorders and life dissatisfaction do significantly impact functional participation and QOL in adult post stroke survivors Conclusions to be made: 66% experience dissatisfaction with life due to activity limitations and restricted participation in IADLS, ADLS, and work related tasks. Summary of Findings Cont’d… Those w/ and w/o mood disorders experience improved participation and performance in ADLs, IADLs, and role participation through client-designation of goal activities and meaningfulness of the activity. Those w/ mild cognitive impairments experience limited participation in social, educational, high and low demand leisure activities; though depressive symptoms did not show a retained participation in comparison to those without depressive symptom. Those w/ emotional changes (depression/lability) directly impact acute occupational engagement and hinder LT recovery and re-engagement in occupations. Those w/ depression and mood dysfxns that receive immediate, intensive, consistent, regular, and early initiation of professional social support can improve emotional regulation and depressive/psychiatric mood management Summary of Findings Cont’d… Those experiencing life dissatisfaction, when engaging in a collaborative lifestyle intervention group are able to more effectively ID limitations in occupations that are meaningful Those that may not necessarily have depression but do demonstrate depressive s/s do in fact experience life dissatisfaction with time use spent in occupational participation; particularly in those w/ less affectionate support. Those w/ depression and mood dysfunctions that receive immediate, intensive, consistent, regular, and early initiation of professional social support can improve emotional regulation and depressive/psychiatric mood management. Those w/ psychological distress and impaired cognitive function are Ily associated with lower reports of perceived QOL. Summary of Findings Cont’d… Those w/ younger age, motor impairments, unemployment, cognitive and motor impairments, fatigue, and depressive symptoms have unmet demands relating to work skills, intellectual fulfillment, and leisure time that impair their QOL. Those w/ depression experience the lowest QOL within the first six months of onset, from six to twelve months is positively influenced by social support, educational qualifications, and occupational status. Those w/ subtle residual deficits (depression, impaired executive function, attention) have less life satisfaction and QOL. Those w/ and w/o depressive s/s and w/ and w/o cognitive impairments can improve in fx’l participation after engagement in a repetitive therapeutic task practice Exercise can have a positive effect on mood, modifying its effect on functional recovery, and improve QOL in stroke survivors w/ depressive s/s Refocusing of Health Care Goals-New Opportunity! OT’s need to develop a knowledge base shown to be effective in enabling those with disability to live more meaningfully and productively Need to abandon biomechanical reasoning and incorporate psychosocial reasoning as well as evidence-based practice OT’s need to shift from reductionism back to holism to fully assess quality of life OT’s also need to advocate for occupation based practice and client centered interventions to address all aspects of humanism-not just a physical disability! 23 Objectives Background and challenges of acute care today Literature review Summary of findings- New opportunities! Conceptual models The Future of Occupational Therapy Conceptual Models in Acute Care Conceptual models Lifestyle Performance Model (LSPM) Models in psychiatric/mental health settings MOHO, PEO, OA, and Ecology of Human Performance most often used Most therapists don’t use just one, they combine Little to no studies on the LSPM Some relating to COPM 25 The Lifestyle Performance Model Designed to give the OT the basis to perform sophisticated assessment and treatment that truly impacts a person’s quality of life through purposeful activity. Allows for incorporating relevant data into documentation which guides the intervention plan. Can be used with other-treatment based frames of reference as an over-arching model. Drives client centered, occupation based practice interventions for a treatment plan “specially made” for the client 26 The Lifestyle Performance Model (cont.) 4 Domains of the LSPM patient profile, equal in importance and socioculturally specific: - Self-Care/Self-Maintenance - Intrinsic Gratification - Societal Contributions - Reciprocal Interpersonal Relatedness Environment: All of the above must be considered given the context in which these activities take place including how the environment hinders or contributes to occupation. 27 Communicating findings to practice, funders, clients, and managers Multidisciplinary daily stroke rounds Anti-depressants, mood screens, communicate findings Family, caregiver, patient education re: mood and emotional regulation/depression, participation and life satisfaction/QOL Make it personal Managers can acknowledge the need for consistent caseloads for maintain consistency/rapport Improvement in motivation/participation/mood i.e. screens/assessments can improve function i.e. FIM scores= $ Justifies need for psychosocial management in acute care for LT prognostic recovery Ensure documentation reflects functional, medical, skillable and reimbursable needs Communicate findings to coworkers, symposiums, state/international conferences Objectives Background and challenges of acute care today Literature review Summary of findings- New opportunities! Conceptual models The Future of Occupational Therapy Overview Hospitals need new approaches to improve communication and pt satisfaction Health systems are reimbursed based on quality services Patients are most frequently seen longitudinally in acute care and not only value it- but significantly benefit from occupation OT’s know their role, but are interested in finding out more information with tools that are quick, effective, and beneficial…LSPM! 30 Conclusion OT is moving back to holism Acute care needs an innovative approach focused on the client with assuring quality care Health systems will pay for quality care provided People need occupation for recovery People value occupational engagement to promote overall health and well being by improving functional independence OT’s value theory and conceptual models though need more education on how to utilize them LSPM incorporates 4 holistic domains and is quick, easy, and encompassing OT’s are the ones to drive the movement towards improving quality of life and recovery in acute care through the use of the LSPM to identify meaningful occupations 31 Wrap Up! When a patient does what is familiar, enjoyable and what they want to achieve; they are inadvertently developing their own treatment program. Occupation based practice and client centered interventions drive motivation and willingness to participate Find what makes them tick and submerge them in those meaningful activities to get “flow” to happen Our expertise is to direct the engagement in occupation to support participation. Be the means to achieve! 32 Overall Benefits of Occupational Engagement Differentiated us from other disciplines and increased respect for OT throughout the institution. Has produced improved patient outcomes. Enhanced meaningful engagement Positive perception of a good therapeutic experience Illustrated the benefits of true functional independence Has significantly increased OT referrals from other disciplines. Has increased role clarity for therapists and students. Influenced multidisciplinary treatment approaches, therapeutic styles, and holistic interventions Increased recognition for the power of human engagement Elicited psychosocial impact with patients and families that value occupational engagement 33 Integrating Occupation into Treatment Session Occupation= meaningful activity as a therapeutic tool. Need to define OT’s role, reclaim occupation. Looking at Quality of Life and changing life-style to promote physical, cognitive, and emotional wellbeing. Exploring ways to continue life style roles with physical/cognitive limitations. Need to use assessment tools with data supports observations. Ensure documentation reflects measurable data, capture the “flow”. Exploring patients contributions to society. Moving past function Quality and Balance life-style. 34 The Future of Occupational Therapy For OT to survive and flourish in the rehab setting we must: Learn about all the resources in the community Be able to assess and address complex biopsychosocial issues in a wide variety of patient population and setting. Be able to provide sophisticated, authentic, occupational therapy based on sound conceptual models and frames of reference. Utilize valid assessment tools to design treatment and utilize evidence based practice. Integrate OTs unique ability to utilize occupation as a therapeutic tool. 35 The Future of Occupational Therapy (cont’d) New paradigm shift: the need for evidence based practice Requires measurable and reimbursable evaluations, treatment plans, interventions, and holistic assessments. All OT’s acknowledge need for more research, though few are doing it! Few studies exist regarding the use of occupation in acute care/acute rehab medical settings NO evidence exists relating to the use of the LSPM as a conceptual model in this setting 36 Speaking of Research: Top 5 Research Articles Relating to Occupation in Acute Care as of 2012: Studies showing OT has a positive effect in acute care ○ Brahmbhatt, N., Murugan, R., & Milbrandt, E.B. (2010). Early mobilization improves functional outcomes in critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine, 14: 321. ○ Wressle, E., Filipsson, V., Andersson, L., Jacobsson, B., Martinsson, K., & Engel, K. (2006). Evaluation of occupational therapy interventions for elderly patients in Swedish acute care: A pilot study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 13, 203-210. Studies showing the nature of OT in acute care ○ Craig, G., Roberson, L., & Milligan, S. (2004). Occupational therapy practice in acute physical health care settings: A pilot study. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(1), 5-13. ○ Griffin, S.D., & McConnell, D. (2001). Australian occupational therapy practice in acute care settings. Occupational Therapy International, 8(3), 184-197. Study showing occupation based intervention use in acute care ○ Eyres, L., & Unsworth, C.A. (2005). Occupational therapy in acute hospitals: The effectiveness of a pilot program to maintain occupational performance in older clients. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 52, 218-224. 37 Any Questions?? References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. American Occupational Therapy Association (2009). American Occupational Therapy Association fact sheet: Occupational therapy in acute care. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press. American Occupational Therapy Association. (2008). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (2nd ed,). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 625-683. Atwal, A. (2002). A world apart: How occupational therapists, nurses, and care managers perceive each other in acute health care. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65, 446-452. Baum, C. (2000, January 3). Occupation-based practice: Reinventing ourselves for the new millennium. OT Practice 5(1), 12-15. Bigliusi, U., Eklund, E., & Erlandsson, E.K. (2010). The value and meaning of an instrumental occupation performed in a clinical setting. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 17, 4-9. Blaga, L., & Robertson, L. (2008). The nature of occupational therapy practice in acute physical care settings. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(2), 11-18. Bloch, M.W., Smith, D.A., & Nelson, D.L. (1987). Heart rate, activity, duration, and the affect in added-purpose versus single-purpose jumping activities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43, 25-30. Brahmbhatt, N., Murugan, R., & Milbrandt, E.B. (2010). Early mobilization improves functional outcomes in critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine, 14: 321. Bynon, S., Wilding, C., & Eyres, L. (2007). An innovative occupation-focused service to minimize deconditioning in hospital: Challenges and solutions. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 54, 225-227. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. (2002). Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective (rev. ed.). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Author. Chisholm, D., Dolhi, C., & Schreiber J. (2004). Occupational therapy intervention resource manual: A guide for occupation-based practice. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Learning. Cheah, S., & Presnell, S. (2011). Older people’s experiences of acute hospitalizations: An investigation of how occupations are affected. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 120-128. Craig, G., Roberson, L., & Milligan, S. (2004). Occupational therapy practice in acute physical health care settings: A pilot study. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51(1), 513. Crennan, M., & MacRae, A. (2010). Occupational therapy discharge assessment of elderly patients from acute care hospitals. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 28(1), 33-43. Crist, P.A., Royeen, C.B., & Schkade, J.K. (Eds). (2000). Infusing occupation into practice (2nd ed.). Bethesda, MD. American Occupational Therapy Association. Cusick, A. (2001). The experience of clinician-researchers in occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 9–18. Eakman, A.M., & Nelson, D.L. (2001). The effect of hands-on occupation on recall memory in men with traumatic brain injuries. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 21, 109-114. Eyres, L., & Unsworth, C.A. (2005). Occupational therapy in acute hospitals: The effectiveness of a pilot program to maintain occupational performance in older clients. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 52, 218-224. Fasoli, S.E., Trombly, C.A., Tickle-Degnen, L., &Verfaellie, M. H. (2002). Context and goal-directed movement: The effect of materials-based occupation. OTJR: Occupation, Participation, and Health, 22, 119-128. Ferguson, J.M., & Trombly, C.A. (1997). The effect of added-purpose and meaningful occupation on motor learning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 51, 508-515. Fleming, J.M., Lucas, S.E., & Lightbody, S. (2006). Using occupation to facilitate self-awareness in people who have acquired brain injury: A pillow study. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 44-55. Griffin, S. (2002). Occupational therapy practice in acute care neurology and orthopaedics. Journal Of Allied Health, 31(1), 35-42. Griffin, S.D., & McConnell, D. (2001). Australian occupational therapy practice in acute care settings. Occupational Therapy International, 8(3), 184-197. Hinojosa, J., & Blount, M. (Eds). (2000). The texture of life: Purposeful activities in occupational therapy practice. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association. Holst, C., & Vogt, D. (1999). Empowering occupational therapy. Columbia, MO: TheraPower. Jackson, J.P., & Schkade, J.K. (2001). Occupational adaptation model versus biomechanical-rehabilitation model in the treatment of patients with hip fracture. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 531-537. 39 References 26. Kielhofner, G. (2004). Conceptual Foundations of Occupational Therapy. (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA. F.A. Davis Company. 27. Kircher, M.A. (1984). Motivation as a factor of perceived exertion in purposeful versus nonpurposeful activity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 38, 165-170. 28. Lang, E.M., Nelson, D.L., & Bush, M.A. (1992). Comparison of performance in materials-based occupation, imagery-based occupation, and rote exercise in nursing home residents. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46, 607-611. 29. Law, M. (Ed.). (1998). Client-centered occupational therapy. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. 30. Law, M., Baptiste, S., & Mills, J. (1995). Client-centered practice: What does it mean and does it make a difference? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 250-257. 31. Law, M., Baptiste, S., Carswell, A., McColl, M.A., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. (2005). Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (4th ed.). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists Publications ACE. 32. Law, M., Baum, C.M., & Baptiste, S. (2002). Occupation-based practice: Fostering performance and participation. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. 33. Law, M., Polatjko, H., Baptiste, W., & Townsend, E. (1997). Core concepts of occupational therapy. In E. Townsend (Ed.), Enabling occupation: An occupational therapy perspective. (pp. 29-56). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. 34. Letts, L., Rigby, P., & Stewart, D. (Eds.). (2003). Using environments to enable occupational performance. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. Pierce, D. (2003). Occupation by design: Building therapeutic power. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. 35. Mastos, M., Miller, K., Eliasson, A.C., & Imms, C. (2007). Goal-directed learning: Linking theories of treatment to clinical practice for improved functional activities in daily life. Clinical Rehabilitation, 21, 47-55. 36. McKelvey, J. (2004). Occupational therapy in acute care hospitals. OT Practice, 9(12), CE-1-CE-8. 37. Melchert-McKearnan, K., Deitz, J., Engel, J.M., & White, O. (2000). Children with burn injuries: Purposeful activities versus rote exercise. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54, 381-390. 38. Miller, L., & Nelson, D.L. (1987). Dual-purpose activity versus single-purpose activity in terms of duration on task, exertion level, and affect. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 7, 406-413. 39. Mortera, M. (2007). The OT researcher: achievement through applied scientific inquiry. OT Practice, 12(12), 13-16. 40. Mullins, C.S., Nelson, D.L., & Smith, D.A. (1987). Exercise through dual-purpose activity in the institutionalized elderly. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 5, 29-39. 41. Nagel, M.J., & Rice, M.S. (2001). Cross-transfer effects in the upper extremity during an occupationally embedded exercise. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 317-323. 42. Nelson, D.L., Konosky, K., Fleharty, K., Webb, R., Newer, K., Hazboun, V.P., et al. (1996). The effects of an occupationally embedded exercise on bilaterally assisted supination in persons with hemiplegia. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 50, 639-646. 43. Phipps, S., & Richardson, P. (2007). Occupational therapy outcomes for clients with traumatic brain injury and stroke using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 328-334. 44. Price, P., & Miner, S. (2007). Occupation emerges in the process of therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 441-450. 45. Rebeiro, K.L., & Cook, J.V. (1999). Opportunity not prescription: An exploratory study of the experience of occupational engagement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66, 176-187. 40 References 46. Retchin, S., Clark, R.R., Downey, W.B. (2005). Contemporary challenges and opportunities at academic health centers. Journal of Healthcare Management, 50, 121-135. 47. Rexroth, P., Fisher, A.G., Merritt, B.K., & Gliner, J. (2005). ADL differences in individuals with unilateral hemispheric stroke. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72, 212-221. 48. Ross, L.M., & Nelson, D.L. (2000). Comparing materials-based occupation, imagery-based occupation, and rote movement through kinematic analysis of reach. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 20, 45-60. 49. Sakemiller, L.M., & Nelson, D.L. (1998). Eliciting functional extension in prone through the use of a game [case report]. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 52, 150-157. 50. Schmidt, C.L., & Nelson, D.L. (1998). A comparison of three occupation forms in rehabilitation patients receiving upper extremity strengthening. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 16, 200-215. 51. Shah, S., Vanclay, F., & Cooper, B. (1990). Efficiency, effectiveness, and duration of stroke rehabilitation. Stroke; A Journal Of Cerebral Circulation, 21(2), 241-246. 52. Sietsema, J.M., Nelson, D.L., Mulder, R.M., Mervau-Sheidel, D., & White, B.E. (1993). The use of a game to promote arm reach in persons with traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47, 19-24. 53. Smith-Gabai, H. (Ed.). (2011). Occupational therapy in acute care. Bethesda, MD: The American Occupational Therapy Association. 54. Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimension, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1442-1465. 55. Steinbeck, T.M. (1986). Purposeful activity and performance. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 40, 529-534. 56. Sumsion, T. (Ed.). (1999). Client-centered practice in occupational therapy: A guide to implementation. London, Churchill Livingstone. Velde, B., & Fidler, G. (2002). Lifestyle Performance: A model for engaging in the power of occupation. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. 57. Thibodeux, C.S., & Ludwig, F.M. (1998). Intrinsic motivation in product-oriented and non-product-oriented activities. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 42, 169-175. 58. Thomas, J.J., Vander Wyk, S., & Boyer, J. (1999). Contrasting occupational forms: Effects on performance and affect in patients undergoing Phase II cardiac rehabilitation. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 19, 187-202. 59. Velde, B. P., & Fidler, G.S. (2002). Lifestyle Performance: A model for engaging the power of occupation. Thorofare, NJ. Slack Inc. 60. Ward, K., Mitchell, J., & Price, P. (2007). Occupation-based practice and its relationship to social and occupational participation in adults with spinal cord injury. OTJR: Occupation, Participation, and Health, 27(4), 149-156. 61. Wressle, E., Filipsson, V., Andersson, L., Jacobsson, B., Martinsson, K., & Engel, K. (2006). Evaluation of occupational therapy interventions for elderly patients in Swedish acute care: A pilot study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 13, 203-210. 62. Wu, C., Trombly, C.A., & Lin, K. (1994). The relationship between occupational form and occupational performance: A kinematic perspective. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48, 679-687. 63. Yoder, R.M., Nelson, D.L., & Smith, D.A. (1989). Added-purpose versus rote exercise in female nursing home residents. American Journal of Occupational, 43, 581-586. 64. Zimmerer-Branum S., & Nelson, D.L. (1995). Occupationally embedded exercise versus rote exercise: A choice between occupation forms by elderly nursing home residents. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49, 397-402. Revised 1/12/2015 per Dr. Julia Glenn, OTD, OTR/L, C-GCM 41