j_smith_CPSA_2009_Paper - AUSpace

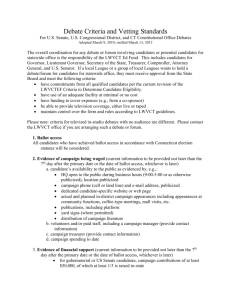

advertisement