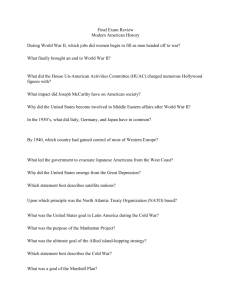

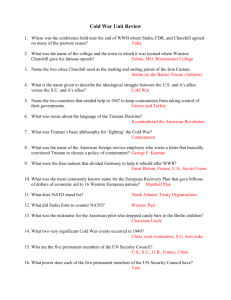

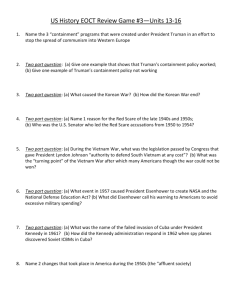

Modern American History Online Textbook

advertisement