ExpositoryText_RRISD_Session_1_Launch_R

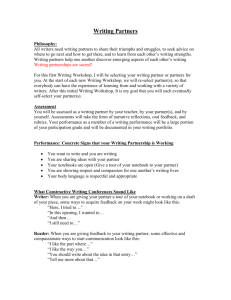

advertisement

Expository Text: Teaching students to explain, inform, argue, and reflect Michelle Fowler-Amato & Lynn Masterson Heart of Texas Writing Project August 10, 2011 Agenda 1. Introductions 2. Writing workshop and processes 3. Writers’ notebooks 4. Understandings of expository genres 5. Reading in a genre: Models and strategies 6. Writing in a genre 7. For next time… Introductions Michelle Lynn Getting to know you Name tent School Grade Six-word Memoir http://www.smithmag.net/sixwords/ Capable Writers Take a few minutes to list the attributes you associate with a person who is a “capable” writer. What kind of classroom environment would support the development of a capable writer? English: What to Teach (Bomer, 2011) Take a few minutes to look back through Chapter 1 of Building Adolescent Literacy in Today’s English Classrooms to situate yourself back in the text. Choose what you believe is the most important sentence in the chapter. Write the sentence and page number on a blank page in your writer’s notebook and write about why you chose this sentence. Then write a question you have about the text Share with your table Share whole group A Class is an Organization of People Independent work Partnerships Small Groups What a Class Period Can Be In a 50 minute period… Mini-lesson (10 minutes) Work time (30 minutes) Sharing (10 minutes) Other Possible Structures Mentored Inquiry Whole-class Discussion Shared Aesthetic Experience Essential Characteristics of a Writer’s Workshop Safe Environment Encouraging risk taking Clear guidelines for assessment Choice Choices about daily work in the workshop, content, development, genre, form, publication Time Regularly scheduled writing time on a weekly basis Talk Interactions with teachers and peers about their writing High Expectations Everyone will write and everyone will publish Teaching Organized for Writers Writers’ Workshop Over time in a writers’ workshop we hope to see students developing: A sense of self as writers, as well as a personal writing process that works for them; A way of reading the world like writers, collecting ideas with variety, volume and thoughtfulness; A sense of thoughtful, deliberate purpose about their work as writers, and a willingness to linger with those purposes; As members of a responsive, literate community; Ways of reading text like writers, developing a sense of craft, genre and form in writing; A sense of audience, and an understanding of how to prepare writing to go into the world Components of a Writer’s Workshop Focus Lessons/Mini Lessons Procedural Lessons: important information about how the workshop runs (how to get or use materials, where to confer with a friends, etc). Writing Process Lessons: strategies writers use to help them choose, explore, or organize a topic Qualities of Good Writing Lessons: information to deepen a student’s understanding of literary techniques: use of scenes, influence of point of view, strong language, leads and endings, etc. Editing Skills: information to develop their understanding of spelling, punctuation and grammatical skills Components of a Writer’s Workshop Focus Lessons/ Mini Lessons short, focused and direct taught to a group of students or the whole class topic varies according to the needs of the class A mini lesson does not always direct the course of action for the rest of the workshop. This is the time to introduce an important skill but we shouldn’t expect students to spend the next 40 minutes practicing it. Teachers can direct student practice during the mini lesson but when the lesson ends students return to ongoing writing projects Components of a Writer’s Workshop Independent Writing Time Freewriting in a notebook to develop, play around with, or extend ideas—use as a tool for thinking. Writing Exercises Reading to support writing Staring off into space Drafting, revising, or editing a writing project Conferencing with teachers or peers Publishing a writing project Components of a Writer’s Workshop Sharing A special time at the end of each workshop for students to share writing with the whole class Teacher coaches students how to give and receive responses to each others writing It is more than a celebration but also a time for teaching Teachers direct students to act in ways that will help them when they are conferring one-on-one with peers Components of a Writer’s Workshop Conferencing The majority of teaching takes place in the conference Conferencing happens at all stages of the writing process Conferencing guides the types of minilessons included in a unit of study Focused Units of Study Process Living a writing life, and getting and growing ideas for writing A writer’s work other than writing: research, observation, talk, etc. An overview of the process of writing Revision Editing Using a notebook as a tool to make writing better How writers have peer conferences How writing gets published Studying our histories as writers How to coauthor with another writer Focused Units of Study Products An overview of the kinds of writing that exist General craft study: Looking closely at good writing and naming the qualities we see Specific craft study: Zooming in on some aspect of craft-structure, punctuation, word choice, leads, endings, paragraphing, descriptions, etc. How to make illustrations work with text Finding mentor authors for our writing Specific genre study: specifically editorials, feature articles, essays, reviews, etc. Write Like a Teacher of Writing “We write so that we know what to teach about how this writing work gets done. We write so that we know what writers think about as they go through the process. We write so that our curriculum knowledge of the processes of writing runs deep and true in our teaching. We write so that we can explain it all.” -Katie Wood Ray I am a writer who… steals minutes to write -Kelly tends to hide out in particular genres –Michelle has a zillion things to say but won’t allow herself to speak –Samantha throws words on the page to see what sticks –Ann must have colorful ink to compose with -Amber I am a writer who… Take a few minutes to think about your own writing life. When do you write? Why do you write? What do you need to write? What do you do while in the process of writing? I am a writer who… Teaching From Our notebooks “As teachers of writing, we spend time reading the texts of our experiences as writers because the curriculum of process (how it happens that someone gets writing work done) is folded into the layers of meaning in these texts.” -Katie Wood Ray Writers’ Notebooks: Tools for Self-sponsored Thinking “A writer’s notebook is meant to change the way the user pays attention to the world. The writer notices more because she has a notebook and a responsibility to write in it. She has a problem to solve-what to put in a notebook today-and the solution to that problem involves tuning into her own thoughts-noticing when she has them, becoming aware of their relationships, and following them where they might lead.” -Randy Bomer Why Use a Notebook? In a notebook, a writer might: collect ideas, noticings, wonderings gather information on a particular topic respond to literature try on language Why Use a Notebook? In a notebook, a writer might: experiment with the arrangement of text return to past entries to build on ideas rehearse for crafted texts that are created for an audience reflect on processes take notes on writing strategies or editing devices Collecting in notebook Reflecting/selfassessing Finding a topic Publishing to audience Collecting around topic Editing/Clarifying Envisioning text Revising/Rethinking Drafting rapidly Choosing the Right Notebook A notebook must meet the needs of the writer. In choosing a notebook, a writer might consider: the purpose of the notebook the size lines or no lines? room to sketch? Choosing the Right Notebook: Turn and Talk What type of notebook will work for you? What type of notebook will work for your students? Writers’ Notebooks in the Classroom When making use of writers’ notebooks, teachers should plan to: create space for students to write every day teach stamina and concentration confer with student writers, and make note of these conversations encourage variety Finding that Balance “A teacher has to establish a balance between (a) giving students lots of space for decision making and (b) providing enough support so that they don’t feel abandoned and empty. That balance is crucial throughout the teaching of notebooks, and the key is to make students responsible for making decisions, but to teach actively what they need to know to make good decisions.” -Randy Bomer Classroom Reflection: Turn and Talk What role might writers’ notebooks play in your classroom? How will you go about providing students with the tools to make “good” decisions? Learning More About Writers’ Notebooks To continue exploring the use of writers’ notebooks in the classroom, check out: Jeff Anderson’s Mechanically Inclined: Building Grammar, Usage, and Style into Writers’ Workshop Randy Bomer’s Time for Meaning: Crafting Literate Lives in Middle & High School Amy Buckner’s Notebook Know-How: Strategies for the Writers’ Notebook Lucy Calkins’ Living Between the Lines Ralph Fletcher’s A Writer’s Notebook: Unlocking the Writer Within You Ralph Fletcher’s Breathing in Breathing Out: Keeping a Writer’s Notebooks Writers’ Workshop Jig-Saw Take 5 minutes to read the handout you received. Each handout outlines one writing teacher’s thinking about the use of writers’ notebooks. On the top right corner of each handout is a sticker. Find those who have the same sticker. Take turns sharing what you learned from your reading. What similarities do you notice? What differences do you notice? What will you take and use in your own classroom? Expository Writing “Problems make good subjects.” -Donald Murray Writing Break: Expository Writing What problem needs solving? What situation needs correcting? What issue needs explaining? What phenomenon needs exploring? What choice I’ve made/stand I’ve taken/personal preference I’ve chosen needs to be understood by others? Classroom Reflection: Turn and Talk What does the reading and writing of expository text look like in your classroom? How do your students respond to reading and writing expository texts? Unmasking the World “If they are to be empowered as serious participants in a democracy, kids have to learn to explain what they think, to argue their perspective, to inform others about subjects in which they can claim their own knowledge and authority. And if they are to be heeded by real readers, young writers have to learn to write well, engagingly and clearly in these crucial genres.” ~Randy Bomer Living a Writer’s Life While at lunch, try living like a writer. Turn on your observation skills and jot down some noticings in your notebook: eavesdrop, collect images and wonderings. Stir your memory. fiction nonfiction fiction nonfiction Our focus is on the texts and how they are shaped – not on what is real or not real TEXT FORMS narrative expository narrative structured in time expository structured by category Narrative I still had a couple of hours to kill before meeting Alejandra. “I might bring Ram. He might need it.” She’d told me all about Ram’s brother, how he was brain-dead, how it happened, the whole story. The whole thing made me sad. I thought of that day at the cemetery. I thought of how I’d dropped him off at the hospital. I thought of that sadness in his eyes. It felt like something inside him had died or was dying. Something like that. So what the hell did I have to be sad about? No one in my house was dying. Not that we weren’t brain dead. I took off in my car and found myself driving back home. Okay so I was going back home. What was I going to do in the rain? When I pulled up to the driveway, David’s car was sitting there. You know, like it belonged. Expository In their quest to spread their seeds, plants have proved endlessly adaptable. Some, such as dandelions, produce spores that can fly miles on a puff of wind. Others, like coconuts, have engineered seeds that can survive thousand-mile voyages at sea. Some of the most remarkable seeds, however, are those adapted to survive fires so intense they kill virtually everything else in their path. Many of the world's pine forests, for instance, grow in arid climates, where a single flash of lightning can spark an inferno. Trees that couldn't take the heat died out long ago. Those that remain generate seeds that are fire-hardened better than any high-security safe, able to protect their precious genetic cargo from the heat. Some functions of expository texts To inform To explain To persuade To reflect To instruct or offer advice information •feature articles argument •letters •pamphlets •editorials reflection •essays explanation •concept papers To instruct or offer advice •Consumer reports •Advice columns •Self-help books •Guide books Argument Gather 'round children, and a true tale I'll tell, about how privatization does not go well. In the past decade or so, there has been a rush by public officials to privatize government functions. Corporations, they cried, can do any public job better and cheaper. So, on that theoretical assumption, everything from water systems to social services have been turned over to corporations for their fun and profit. In case after case, the profits came, but at the expense of the public, for the corporations achieved their so-called "efficiencies" by replacing experienced government employees with low-wage workers and cutting service to the people. Explanation The word after "infinity" in my dictionary is "infirm," a definition of which is "weak of mind." This is how many of us who are not mathematically inclined feel upon contemplating infinity. We feel weak because our finite minds can only go so far with the concept, and because every time we think we're on the verge of securing even a shadowy understanding, we're tripped up by something. A friend of mine once told me that trying to hold her hyperactive toddler was like trying to hold a live salmon. Infinity is like that for us "infirm ones": slippery as a salmon, forever eluding our grasp. This is true no matter how you approach the concept. Many of us might consider numbers the most sure-footed way to come within sight of infinity, even if the mathematical notion of infinity is something we'll never even remotely comprehend. We may think, for starters, that we're well on our way to getting a sense of infinity with the notion of no biggest number. There's always an ever larger number, right? Well, no and yes. Mathematicians tell us that any infinite set—anything with an infinite number of things in it—is defined as something that we can add to without increasing its size. The same holds true for subtraction, multiplication, or division. Infinity minus 25 is still infinity; infinity times infinity is—you got it—infinity. And yet, there is always an even larger number: infinity plus 1 is not larger than infinity, but 2infinity is. Reflection I hate happiness. Particularly jocularity on demand. I have always refused to smile on cue. When I was a child we posed for family portraits at the local suburban shopping mall photography studio. My grinning parents and cousins all look like the typical middle class suburban family while the expression on my face would suggest that I'm about to be marched on a pogrom from our shtetl in Russia. I love melancholic novels, depressed poets, and pessimistic prognosticators. I like sad songs, weepy movies, I'm a sentimental drunk. My idea of a good time is drinking a double espresso while reading Death in Venice. Venice is my idea of a rollicking good time town. I was never a waitress. Not perky enough. I had just enough natural attitude to work the door of a popular NY nightclub in the late '80s. In fact, I probably turned you away, for no reason at all, just because you really, really wanted to come in. I was never a cheerleader, never an ingénue, never the homecoming queen. Feature Article – “Penny Dreadful” Several years ago, Walter Luhrman, a metallurgist in southern Ohio, discovered a copper deposit of tantalizing richness. North America’s largest copper mine—a vast openpit complex in Arizona—usually has to process a ton of ore in order to produce ten pounds of pure copper; Luhrman’s mine, by contrast, yielded the same ten pounds from just thirty or forty pounds of ore. Luhrman operated profitably until mid-December, 2006, when the federal government shut him down. The copper deposit that Luhrman worked wasn’t in the ground; it was in the storage vaults of Federal Reserve banks, and, indirectly, in the piggy banks, coffee cans, automobile ashtrays, and living-room upholstery of ordinary Americans. A penny minted before 1982 is ninety-five per cent copper— which, at recent prices, is approximately two and a half cents’ worth. Luhrman, who had previously owned a company that refined gold and silver, devised a method of rapidly separating pre-1982 pennies from more recent ones, which are ninetyseven and a half per cent zinc, a less valuable commodity. His new company, Jackson Metals, bought truckloads of pennies from the Federal Reserve, turned the copper ones into ingots, and returned the zinc ones to circulation in cities where pennies were scarce. “Doing that prevented the U.S. Mint from having to make more pennies,” Luhrman told me recently. “Isn’t that neat?” The Mint didn’t think so; it issued a rule prohibiting the melting or exportation of one-cent and five-cent coins. (Nickels, despite their silvery appearance, are seventy-five per cent copper.) Luhrman laid off most of his employees and implemented his corporate Plan B: buying half-dollars from banks and melting the silver ones (denominations greater than five cents aren’t covered by the Mint’s rule); mining Canadian five-cent coins (which were a hundred per cent nickel most years from 1946 to 1981); and lobbying Congress. Luhrman’s experience highlights a growing conundrum for the Mint and for U.S. taxpayers. Primarily because zinc, too, has soared in value, producing a penny now costs about 1.7 cents. Since the Mint currently manufactures more than seven billion pennies a year and “sells” them to the Federal Reserve at their face value, the Treasury incurs an annual penny deficit of about fifty million dollars—a condition known in the coin world as “negative seigniorage.” The fact that the Mint loses money on penny production annoys some people, because one-cent coins no longer have much economic utility. More than a few people, upon finding pennies in their pockets at the end of the day, simply throw them away, and many don’t bother to pick them up anymore when they see them lying on the ground. (Breaking stride to pick up a penny, if it takes more than 6.15 seconds, pays less than the federal minimum wage.) Advice The Science of Intuition: An Eye-Opening Guide to Your Sixth Sense Gut Feelings You may know what it's like to live on carrot sticks and rice cakes. You may not know that eating intuitively—paying attention to your inner satiety meter—is far more likely to lead to a healthy weight than dieting. After assessing the eating habits of 1,260 female college students, Tracy Tylka, PhD, an associate professor of psychology at Ohio State University, found that those who relied on internal hunger and fullness cues to determine when and how much to eat had a lower body mass index than women who actively tried to control their weight through calorie restriction. In another study, published in 2005 in The Journal of the American Dietetic Association, women who practiced intuitive eating over the course of two years maintained their weight and achieved lower cholesterol levels, lower blood pressure, higher self-esteem, and greater levels of physical activity— while women who dieted over the same period regained any weight they managed to lose and experienced no improvements in their physical or mental health. Further research has shown that intuitive eaters are less likely to think about how their body appears to others, and more likely to spend time considering how their body feels and functions Tune In: Becoming an intuitive eater requires the willingness to sit and listen to your stomach's signals. Eat every three to four hours, before extreme hunger sets in, and stop when you feel nourished and energized, not stuffed. Imagining the portion you want to consume before a meal—and what that will physically feel like afterward—is another way to start trusting your gut. On The Nose There's a reason we say that a bogus idea doesn't "pass the smell test": Research suggests that our nose plays a major role in certain of our judgments, even if we're not aware of the scents we're detecting. In a recent Israeli study, men were asked to sniff a jar containing either fresh women's tears or saline. The participants who smelled tears rated photographs of women as less attractive, and when the researchers tested the men's saliva, they discovered lower levels of testosterone, which correlates with decreased aggression. The scent of tears may have physiologically prompted the men to be more nurturing and appeasing. But scents don't just shape our impressions of a person; they can sway our behavior as well. Research shows that particular odors encourage shoppers to linger over a product and may even make them willing to spend more money. In one study carried out at a clothing store, the scent of vanilla doubled the sales of women's clothes. Tune In: While no one has found a way to increase the number of receptors in the human nose, new research suggests that smelling sweat (your own or someone else's) may increase your nose's sensitivity (thanks to chemicals in the steroids naturally produced by sweat glands). More reason to get moving: Exercise itself temporarily improves your olfactory sense, because adrenaline constricts blood vessels in the nose, increasing nasal airflow. Smell receptors that line the inside of your nose regenerate roughly every three weeks, but if you live in an urban area, air pollution can damage the receptors, meaning countryside vacations may temporarily boost sniffing prowess. Genre Exploration • Look through the variety of texts at your table. • With a partner, locate examples of the five (5) expository genres we explored today and label each with a sticky note. Closing Reflection Look back at your first response regarding the “capable” writer. Think about the conversations we had today and add to your initial list of attributes. Now look at your initial thoughts regarding the type of classroom environment you envisioned. Add or make revisions to the types of learning experiences students will need to become capable writers. For Next Time… Live a writer’s life: Collect in your notebook. Read Chapter 11 (What is There to Teach About Writing to Think?) in Building Adolescent Literacy in Today’s English Classrooms. Read Chapter 3 (Feature Article) in Thinking Through Genre (This will be emailed to you). Bring in examples of feature articles that might serve as mentor texts for your students.