guzman, katheleen 5/15/2015 For Educational Use Only

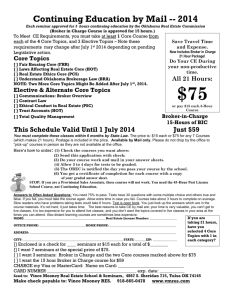

advertisement