Emory-Morrow-Karthikeyan-Neg-GSU-Round7

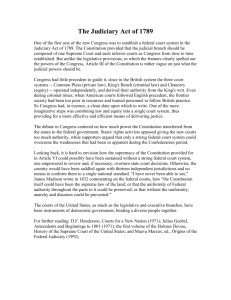

advertisement