Antenatal vitamin D supplementation in a

advertisement

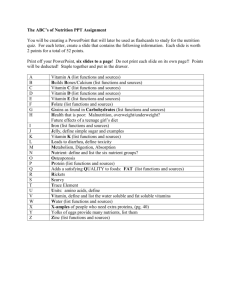

Ealing Hospital NHS Trust Antenatal vitamin D supplementation in a multicultural population in a West London hospital Galea P, Lo H, Kalkur S , T A N T O H L I C K Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Ealing Hospital NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom INTRODUCTION RESULTS CONCLUSIONS Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy has been associated with a variety of One hundred and sixty two women consented to be interviewed and Despite the NICE guidance, implementation of vitamin D supplement is pregnancy complications including an increased risk of pre-eclampsia and were recruited for analysis. A significant 75% of those interviewed were poor even in mothers at greatest risk of vitamin D deficiency. To improve gestational diabetes [1]. It also plays a role in fetal development, of ‘high risk’ ethnicities and a further 23% were obese. Overall, only 52 of our standards, we have recommended various measures including imprinting and immunological function, with a raised susceptibility to mothers (32%) took vitamin D supplements, with a third starting pre- successful implementation of staff education sessions, identification of chronic disease in later life [2]. Furthermore, fetuses of vitamin D conceptually or in the first trimester. Within the ‘high risk’ ethnicities, the women at risk and pro-actively offer them vitamin D supplements in our deficient mothers are at risks of neonatal hypoglycaemia, seizures, heart overall compliance in vitamin D supplementation was less than a third early pregnancy unit. failure and rickets [3]. In 2008, the National Institute for Health and with Caribbean and Middle Eastern women more likely to be left out Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended vitamin D supplementation for (South Asia 53%, Africa 52%, Caribbean 75% and Middle East 70%)(Figure all pregnant women with special emphasis to those at risk of Vitamin D 1). Similarly, only 37% of women with a BMI >30 kg/m2 were given deficiency including women from South Asia, Africa, Caribbean and vitamin D supplements (Figure 2). Vitamin D Middle East and obese women [4]. Both groups are in high prevalence in No vitamin D our population. We audited the compliance of this guidance in pregnant women booked in our hospital to improve our care. Chinese 0 No vitamin D 23 Vitamin D 13 1 2 Other Black No Vitamin D 3 Africans 8 Vitamin D 6 Caribbean 3 1 Other Asians METHODS 19 Figure 2. Vitamin D intake in pregnant women with a BMI≥30kg/m2. The 10 Pakistan 7 3 A prospective audit of 162 mothers delivered during a 2-month period Indians Any other mixed (5th February 2011 – 5th April 2011) at Ealing Hospital Trust. Women were verbally consented and interviewed by a team member using a standardized questionnaire as regards to prescribing, usage and 0 White and Black 0 1 1 Any other white 23 5 White Irish 0 1 White British compliance of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy. Their data labels are the actual number of patients (n=36). 42 17 8 1 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 demographics were collected from their medical records. The audit was registered with our hospital’s Clinical Governance audit department. National Research Ethics Service (NRES UK) exempted the project from ethics approval as it was considered an Audit. Figure 1. Vitamin D intake according to ethnicity. The data labels denote the actual number of in that group (n=162) Correspondence: paula.galea@doctors.net.uk References: 1. Lewis, S., et al., Vitamin D deficiency and pregnancy: from preconception to birth. Mol Nutr Food Res. 54(8): p. 1092-102. 2. Kovacs, C.S., Vitamin D in pregnancy and lactation: maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes from human and animal studies. Am J Clin Nutr, 2008. 88(2): p. 520S-528S. 3. Mulligan, M.L., et al., Implications of vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and lactation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 202(5): p. 429 e1-9. 4. Antenatal Care: Routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance, ed. R. press. 2008, London: National Collaborating Centre for Women' and Children's Health (UK).