Paradigms - Trauma Conference

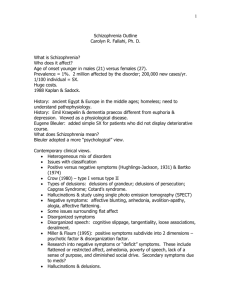

advertisement

The Turn of the Paradigm?: Madness, Differential Sensitivity and Early Life Experience Andrew Moskowitz Aarhus University Kristiansand 4 June 2015 A formative clinical experience Outline of talk How do paradigms change? What is the current, biomedical paradigm of psychosis/mental illness? How well has it worked? What could an alternative – socio-psycho-bio – model of mental disorders look like? Supportive evidence Diathesis/stress vs differential susceptibility Early life experiences/disorganized attachment and a possibly relation to delusions Paradigms and psychopathology Current paradigm of mental illness, emphasizing genetics and brain pathology, has failed An emerging trauma/dissociation/attachment paradigm shows real promise Such a paradigm may be supplemented by conceptualizing individuals not as vulnerable to negative influences, but as sensitive or susceptible to environmental influences - for better or worse Thomas Kuhn and The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) Kuhn’s argument Science does not advance in a linear fashion Myth: More and more accurate data collected over time so that reality or truth is more and more closely approximated Rather, science always progresses under the influence of a dominant paradigm Paradigm means a specific past scientific achievement held up as a model or exemplar and the generally accepted beliefs and attitudes of a particular scientific community A paradigm exerts an organizing influence on a field, determining to a large extent what types of research questions are considered legitimate and what sorts of answers are considered acceptable. Ultimately, what is seen and what is not seen Opposing paradigms in psychopathology Schizophrenia field Genetic/biologically caused brain disease Treatment is medications or biomedical technologies Symptoms are meaningless (unconnected to life contexts) Dissociative disorders field DID is caused by overwhelming severe, often sadistic, childhood trauma Treatment is intensive psychotherapy Symptoms have meaning and can be linked to life events DID almost never (and PTSD rarely) considered in any type of schizophrenia research Paradigmatic interpretation of voices To schizophrenia field Voices (auditory verbal hallucinations) are biologically-generated signs of brain disease Content is meaningless Treatment is medications or distraction techniques To dissociative disorders field Voices are psychologicallygenerated indications of unresolved loss or trauma Content is meaningful (split off aspects of the self/ parts of the personality) Treatment involves engaging these parts (which can be challenging) In other words, are psychotic symptoms, such as delusions and auditory hallucinations Random expressions of a diseased brain? OR Encrypted communications of a tortured life? We’ll first explore the former… Basic assumptions of the neo-Kraepelinian paradigm Dominant paradigm of mental disorders stems from Emil Kraepelin According to Klerman (1978), the neo-Kraepelinian credo contains 9 propositions, 4 of which are: Psychiatry is a branch of medicine There is a boundary between the normal and the sick There are discrete mental illnesses… There is not one, but many mental illnesses The focus of psychiatric physicians should be particularly on the biological aspects of mental illness The idealization of Kraepelin Neo-Kraepelinian’s image of Kraepelin as an objective scientist is flawed Diagnostic cards, which formed the basis for his classification system suffered from a ‘lack of systematic rigour’, and served only to ‘supplement and reinforce preconceived (diagnostic) concepts’ (Weber & Engstrom, 1987, pp. 382-383) Kraepelin is described as ‘fanatically’ working through his cards over and over again, as though they were ‘rare art objects’ These preconceived concepts were derived from Kahlbaum and particularly, dementia paralytica or general paresis of the insane Emil Kraepelin and Dementia Paralytica (General Paresis) What was General Paresis of the Insane? A life threatening condition, rampant in early 19th century Europe, that primarily struck young men, combining psychotic symptoms (often grandiosity and impaired judgment) with physical symptoms (including paralysis) Suggested by Bayle (1822) to be linked to syphilis By the late 19th century, this was largely confirmed Fournier, in 1893 and 1894 published a large series of cases (almost 50,000) in which GPI was overwhelmingly linked to syphilitic infections (Kaplan, 2010) He also used index cards to track these cases in ways that foreshadowed Kraepelin’s use By early 20th century, link between syphilis and GPI confirmed by biological studies, leading to the only Nobel Prize for a psychiatrist (Wagner-Jauregg) Who proposed malaria as a treatment! General Paresis as the central paradigm for Kraepelin ‘All his life, he (Kraepelin) had a preoccupation, if not obsession, with alcohol and syphilis… He had no doubt an organic cause would be found for psychiatric illnesses and saw general paresis of the insane as a template for the other illnesses’ (Kaplan, 2010, p.24). ‘General paresis was taken by Kraepelin to be the model disease entity and he hoped that both schizophrenia and manicdepressive disorder would follow suit’ (Jablensky, 1995, p. 186). As late as 1922, in the paper Ends and Means of Psychiatric Research, Kraepelin continued to assert this ‘(R)eaffirming the role of general paresis as his prototype, he declares his central objective to be a “search for unitary morbid processes” which “always arise from similar disease causes”… “what we require above all is a clear characterization of the post-mortem appearances of the brain in as many morbid processes as possible”’ (Shepherd, 1995, p. 191) Post-mortem brain of a General Paresis of the Insane (GPI) patient Model disease entity for Kraepelin (and neo-Kraepelinians) is Dementia Paralytica (GPI) caused by advanced syphilitic infections A genuine neuropsychiatric disorder! General paresis as the exemplar for the neo-Kraepelinian paradigm ‘The example of General Paresis, with the assumption not only that mental disorders were brain disorders, but that any classification of psychopathology was best pursued through identifying brain pathology, not only drove Kraepelin’s typology, but also still underpins that of the current diagnostic systems influenced by his thinking’ (Moskowitz, 2011, p. 350) Gottesman & Shields, prominent psychiatric genetic researchers allied with the neo-Kraepelinians wrote in 1973 of coveting for schizophrenia the solid genetic grounding of ‘pellegra, paresis, tuberculosis, polio, and PKU’ (p. 15) The importance of Kraeplin’s fundamental dichotomy The neo-Kraepelinians championed Kraepelin’s greatest achievement - the distinction between dementia praecox (schizophrenia) and manicdepression (bipolar disorder) - as the cornerstone of their diagnostic system ‘…if the twin pillars of manic-depressive psychosis and schizophrenia are disturbed before there is anything better to put in their place, the roof will come crashing down’ (Kendell, 1987, p. 500) Paradigms and Anomalies According to Kuhn, problems arise for paradigms when no acceptable answers are generated for issues considered fundamental This, along with too many or too important anomalies, pushes a paradigm toward a crisis Anomalies Results not compatible with dominant paradigm occur Example: CERN experiments demonstrating neutrinos traveling faster than the speed of light - not predicted by Einstein’s theory usually ignored or adjustments made to keep fit with paradigm Scientific Revolutions A scientific revolution occurs when an alternative paradigm is proposed that explains some of the anomalies as well as most previous findings Revolutions do not occur in the absence of a suitable alternative paradigm Kuhn suggests that for some revolutions to occur, the ‘old guard’ (‘power elite’) has to ‘die out’! Failures of the neo-Kraepelinian paradigm: schizoaffective disorder Evidence now suggests that schizoaffective disorder is a valid disorder (Marneros & Akiskal, 2007) A disorder between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder was not predicted by Kraepelin, and poses a major challenge for the paradigm A dimension is implied, on the basis of family studies and many other factors Paradigm response? Calls to eliminate schizoaffective disorder. DSM-5 criteria for schizoaffective disorder are even narrower than the DSM-IV. Failures of the neo-Kraepelinian paradigm: nonspecificity of schizophrenic (psychotic) symptoms Increasing evidence that psychotic symptoms are common in the ‘normal’ population and do not differ in nature from those found in schizophrenia (Murphy et al, 2010;Van Os et al, 2008,) Other factors determine symptom persistence and psychiatric diagnosis Psychotic symptoms are common in many disorders, including PTSD (Shevlin et al, 2010), and are not always clearly related in content to the trauma (Scott et al, 2007). ‘Psychotic experience is to the diagnosis of mental illness as fever is to the diagnosis of infection – important but non-decisive in differential diagnosis’ (Fischer & Carpenter, 2009, p. 2081) Failures of the neo-Kraepelinian paradigm: antipsychotic medications Are less effective than previously believed, have more serious side effects and do not act directly on psychotic symptoms ‘(A)ntipsychotics do not primarily change thoughts or ideas; instead, they provide a neurochemical mileau wherein new aberrant saliences are less likely to form and previously aberrant saliences are more likely to extinguish… antipsychotics lessen the salience of the concerns, and the patient “works through” her symptoms toward a psychological resolution’ (Kapur, 2003, p. 17) Failures of the neo-Kraepelinian paradigm: genetic findings Significant overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder ‘new work provides compelling support for the… evidence that schizophrenia and bipolar disorder partially share a common genetic etiology’ (Craddock et al, 2008, p. 483) ‘genetic studies point to a shared neurobiology across the two disorders’ (Thaker, 2008, p. 720) Questionable validity of previously cited genetic findings A large scale, well-designed study found ‘none of the (genetic) polymorphisms were associated with the schizophrenia phenotype at a reasonable threshold for statistical significance’ (Sanders et al, 2008, p. 421) ‘The project to ground our messy psychiatric categories in genes… may be in fundamental trouble’ (Kendler, 2006, p. 1145). ‘The historical effort to ground the categorical nature of schizophrenia in genetic theory has failed’ (Kendler, 2014, p. 5) The dominant paradigm’s response to crisis? Moving the goal posts… ‘As the neo-Kraepelinian edifice begins to crumble, adherents resort to stronger and stronger biological language, as though words such as neuropsychiatry and endophenotypes had the power to restore its once shining façade. The emphasis on endophenotypes… involves exploring putative underlying biological variables that may have only an indirect relationship to the signs and symptoms of mental disorders. For example, … apparent genetic impairments in memory and intelligence as conveying liability for schizophrenia (Toulopoulou et al., 2010). The strong emphasis on endophenotypes, arising from a failure to find clear connections between genetic makeup and psychiatric diagnoses or symptoms, suggests that the neo-Kraepelinian stalwarts have beaten a strategic retreat; at the same time that psychological approaches to treating and understanding psychiatric symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations, have made great strides, the dominant paradigm has given up the traditional territory of mental disorders—the signs and symptoms that people suffer from and that treatments target’. ‘So, the neo-Kraepelinian, categorical, medically based diagnostic system clearly seems to be in a state of crisis. But, as Kuhn has noted, a discipline such as psychopathology will not loosen its grip on a paradigm unless a suitable alternative is available to take its place. What is the evidence that one is appearing?’ (Moskowitz, 2011) The seed planted in the DSM-III The emerging attachment/trauma/ dissociation paradigm Insecure attachment patterns, and particularly disorganized attachment, greatly increases the likelihood of a range of mental disorders, including schizophrenia (Liotti & Gumley, 2008) Childhood trauma, and aversive childhood experiences, change the structure and functioning of the brain in powerful ways – ways that have previously been seen as evidence for a neurobiological disorder (Read, Fosse, Moskowitz & Perry, 2014) Childhood trauma strongly predicts a wide range of mental disorders A prominent psychiatric geneticist, Kenneth Kendler, concluded from a large-scale twin study that childhood sexual abuse was ‘causally related’ to the development of psychiatric and substance abuse disorders (Kendler et al, 2000, p. 953), and that this relationship (at least for major depression) was ‘much stronger’ than for any gene linked to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Kendler, 2006, p. 1140) In addition, there is now extensive evidence, from a range of studies, that childhood trauma specifically predicts psychotic symptoms Dissociation plays a central role not only in DID, but also in PTSD, BPD and possibly schizophrenia (certainly in auditory hallucinations) There may be a range of ‘dissociative’ and ‘non-dissociative’ disorders, or ‘cohesive’ and ‘non-cohesive’ (ego) disorders The emerging attachment/trauma/dissociation paradigm: genetics and brain development Family patterns of psychosis formerly attributed to genetics may be explained by trauma. A large scale case-control and case-sibling comparison concluded: ‘Discordance in psychotic illness across related individuals can be traced to differential exposure to trauma.… Positive psychotic symptoms in vulnerable individuals may arise as a consequence of the level and frequency of exposure to abuse’ (Heins, et al, 2011, American Journal of Psychiatry) Plus the limited genetic evidence that exists is at least partly gene x environment evidence. The field of epigenetics emphasizes the powerful impact of the environment on the expression of genes. ‘(R)odent and non-human primate studies replicate the vulnerability of the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and HPA axis to early-life adversity…’ (Roth And Sweatt, 2011a) ‘To the extent that an increased incidence of schizophrenia is associated with earlylife adversity, epigenetic changes triggered in early prenatal or postnatal developments might predispose the development of schizophrenia later in life’ (Roth and Sweatt, 2011a) The hippocampus and childhood trauma The hippocampus, which is very important for episodic memory and integrative functions, is powerfully affected by chronic stress, particularly in childhood. Teicher et al (2012), on childhood maltreatment and the hippocampus ‘…the most intriguing finding to emerge from this study was evidence for maltreatmentrelated alterations in the subiculum [of the hippocampus], given the importance of this region in the regulation of the HPA axis, dopaminergic responses to stress, and risk for substance abuse and psychosis’ (Teicher et al, 2012) The emerging attachment/trauma/dissociation paradigm: treatment Psychotherapy is effective treatment for psychotic symptoms And can prevent the development of psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia (French et al, 2007, Lemos-Giráldez, 2009) Trauma-based therapies are particularly important ‘Our findings that childhood abuse can influence the content of psychotic symptoms, (suggests) that it is important to assess childhood trauma and trauma-related symptoms in patients diagnosed with psychosis, and to offer a range of treatment options that include trauma-relevant interventions’ (Rieff et al, 2010, p. 363) Van der Berg & Van der Gaag (2012) found that EMDR reduced delusions and some auditory hallucinations in persons with comorbid PTSD and psychosis - even without psychotic symptoms being directly targeted A subsequent study found delusions, but not auditory hallucinations, to improve One further turn of the paradigm Are those who become labeled mentally ill inherently defective, or potentially superior? Are they vulnerable because of an inherent weakness, or more sensitive to influence than others - for worse or for better? Vulnerability to harm vs sensitivity to influence A number of researchers are now suggesting, on the basis of evolutionary theory and empirical research, that some people are more sensitive, for better or for worse, than others. Certain gene alleles (dopamine, serotonin, etc.) may predispose to this Differential susceptibility (Belsky & Pluess) Sensory processing sensitivity (Aron & Aron) Personality type (15-20% in many species) processes sensory information deeply before acting Biological sensitivity to context (Boyce & Ellis) Differences within families are normal and evolutionarily logical Highly supportive or highly aversive environments (including prenatal) increase stress sensitivity/physiological reactivity Differential sensitivity Classic diathesis (vulnerability) – stress model ‘Beyond Diathesis Stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences’ (Belsky & Pluess, 2009) ‘The central thesis in this paper… is that those putatively “vulnerable” individuals most adversely affected by many kinds of stressor may be the very same ones who reap the most benefit from environmental support and enrichment, including the absence of adversity’. (p. 886) This appears to apply not only to children with a difficult temperament, but also to those with genetic variants of the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems (linked to sensitivity to stress), previously seen as indicators of vulnerability to psychosis. Interventions to improve parenting differentially affect the behavior of the more sensitive children (with a specific dopamine gene allele). Poor parenting led to most ‘externalizing behavior’ and sensitivity to stress, while good parenting led to the least. (Van IJzendoorn et al, 2008) Differential susceptibility (sensitivity) model (Ellis et al, 2011) From Bakermans-Kranenburg & Van IJzendoorn (2011) intervention study Time for a paradigm switch? Current ‘medical’ model, neo-Kraepelinian or biopsychosocial (‘biobio-bio’) paradigm has explained little and been faced with numerous ‘anomolies’ New paradigm emphasizing sensitivity (not vulnerability), adverse life experiences - trauma, attachment - and dissociation, better explains current findings - including biomedical ones and Makes evolutionary sense! Social support for a new paradigm Is in a current state of crisis Voice hearing/user/family movements Journalistic critiques of psychopharmacology and medical model Increasing acceptance of high-ranking journals of publications consistent with a new paradigm What to call it? Socio-psycho-biological paradigm? Delusions and early attachment experiences Could delusions - paranoid, grandiose, delusions of reference - be related to early disturbed attachment experiences? Delusions in schizophrenia and emotional arousal Delusional ‘mood’ or ‘atmosphere’ (‘pre-delusional state’) Edinburgh High Risk Schizophrenia study (Cunningham Owens et al, 2005) Depression and anxiety very common in psychotic prodrome (Yung and McGorry, 1996) Other intense mood states – including love and joy – possible (Watts, 2007) Perplexity and foreboding also common (Watts, 2007) ‘Considerable degrees’ of anxiety and depression in high risk sample, particularly in subgroup which later became psychotic anxiety and depression decreased with the development of psychosis ‘anxiety-type phenomena may partially remit as psychotic features escalate’ (p. 390) Thus, delusions may serve to bind or reduce anxiety or other powerful emotions Could some intense affective experiences preceding delusions be memory-related, but not recognized as such? Jaspers’ (1913) classification of delusions Karl Jaspers argued that some delusions were clear explanations for an experience (such as somatic hallucinations) He called these secondary delusions, and argued that they were not specific to schizophrenia Secondary delusions may be, for example, explanations for flashback-related hallucinations, which are not recognized as memory related Sexual abuse survivor’s delusion of ‘snakes in my bed’ Such delusions may serve a defensive purpose - to keep the traumatic memories from reaching consciousness Similar to avoidance in PTSD and compartmentalization in personality parts in DID (which may not be possible for psychotic disorders) Jasper’s Primary delusions But Jasper also described another form of delusion - primary delusions He argued that these were psychologically irreducible or un-understandable Concern was with the form or experience of the delusion, not with its content But delusions did not arise out of the blue, but out of a typical affective state Jaspers on Delusional atmosphere (‘Wahnstimmung’) preceding primary delusions ‘We find that there arise in the patient certain primary sensations, vital feelings, moods, awarenesses: “Something is going on; do tell me what on earth is going on!”… Patients feel uncanny and that there is something suspicious afoot. Everything gets a new meaning. The environment is somehow different – not to a gross degree – perception is unaltered in itself but there is some change which envelops everything with a subtle, pervasive and strangely uncertain light. A living room which was previously felt as neutral or friendly now becomes dominated by some indefinable atmosphere. Something seems in the air which the patient cannot account for, a distrustful, uncomfortable, uncanny tension invades him…This general delusional atmosphere with all its vagueness of content must be unbearable. Patients obviously suffer terribly under it and to reach some definite idea at last is like being relieved from some enormous burden.’ (Jaspers, 1913/1963, p. 98). Jasper’s ‘uncanny’ is the German ‘unheimlich’ An unusual clue from an obscure Freud essay… Freud’s (1919) analysis of feeling ‘uncanny’ (‘unheimlich’) ‘Heimlich’ ‘From the idea of “homelike”, “belonging to the house”, the further idea is developed of something withdrawn from the eye of strangers, something concealed, secret’ (p. 225). Freud argued that Heimlich could be transformed into its opposite Unheimlich He quotes Schelling to say: “‘Unheimlich” is the name for everything that ought to have remained . . . secret and hidden but has come to light’ (p. 224). Freud argued that the feeling of uncanniness related to ‘secretly familiar’ (p. 245) infantile experiences that had been repressed but that had been ‘once more revived by some impression’ (p. 249). The original feeling need not have been negative; the uncanniness is due to the uncalled-for repetition, the re-emergence of the familiar in an unfamiliar context A speculative association of early attachment experiences with Wahnstimmung Disturbing attachment experiences from the 1st few months of life, particularly those associated with disorganized attachment (parent as frightening or frightened), can be stored as emotional memories (because the amygdala is active), but without any autobiographical context (because the hippocampus is not yet fully functional). There is some evidence that disorganized attachment (followed by a dismissing attachment style) may be related to schizophrenia Such emotional memories would likely share many components with Wahnstimmung - including fear, confusion, and foreboding In addition, early attachment memories can include rudimentary conceptions of self and other - as perpetrator, victim or rescuer - which could underlie subsequent paranoid or grandiose delusions Such decontextualized affective states could be triggered by situations somehow reminiscent of these early attachment situations, or perhaps simply by the activation of the attachment system, in a special context These experiences cannot be recalled as memories (and thus need not be repressed or dissociated), because the autobiographical memory system/hippocampus is not fully active before age two The trajectory from early attachment experiences to psychopathology Disorganized attachment has also been linked to DID and Borderline Personality Disorder Liotti (2009) speculates that subsequent childhood trauma is required for DID Emotional abuse and neglect emphasized more in psychosis research Clinical experience supports this Than sexual abuse Differences in the type of trauma across groups? Perhaps also capacity for dissociation differs? Delusions are needed when dissociation is limited? Are we witnessing a turn of the paradigm? Perhaps… Will only happen if Delusion that brain studies can explain everything is overcome Delusion that those diagnosed with mental disorders are fundamentally different from the rest of us is overcome Fear of PTSD and dissociative disorders by psychosis field is overcome And this conference is a great start! More careful longitudinal studies are conducted Clinically More approaches from trauma and dissociation field should be tried with psychotic disorders ‘You think you’re better than us, don’t you? You think this could never happen to you’… The last word from Carl Jung’s (1908) The Content of the Psychoses ‘(W)e can maintain with complete assurance that in dementia praecox there is no symptom which could be described as psychologically groundless or meaningless. Even the most absurd things are nothing other than symbols for thoughts which are not only understandable in human terms, but dwell in every human breast. In insanity, we do not discover anything new and unknown; we are looking at the foundations of our own being, the matrix of those vital problems on which we are all engaged.’