File

advertisement

Statutory and common law duties to

consult over reductions and removals of

services: The potential impact of the Public

Sector Equality Duty

Mr. Jamie Grace (Helena Kennedy Centre for

International Justice)

Introduction

An overview of the paper (1)

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

PSED came into force on the 5th April 2011.

The potential impact of the PSED in challenging cuts by way of judicial

review?

The best part of five years of cuts to come?

Five-year period in which human rights-based JR might fundamentally

change?

A Westlaw search on 1st June 2015 for the phrase "public sector

equality duty" shows 74 case reports since September 2013, when the

Government Equalities Office report on the Review of the Public Sector

Equality Duty noted that:

" Although the [relative] number of JRs brought under the PSED is low, it is

still a significant proportion of the overall number of JRs and there have

been several high profile cases..."

The doctrinally-significant Court of Appeal decision in Bracking on 6th

November 2013 had been cited 19 times by 1st June 2015.

The PSED is probably still developing, doctrinally-speaking

Challenging cuts on human rights grounds vs.

challenging cuts on PSED grounds?

Economic/cost-based rationale for welfare cuts

can be using either, but which is more

effective?

•

McDonald v UK (4241/12) 37 B.H.R.C. 130; Times, June 13, 2014

(ECHR)

•

Confirming R. (on the application of McDonald) v Kensington and

Chelsea RLBC [2011] UKSC 33; [2011] 4 All E.R. 881 (SC)

•

Article 8 ECHR engaged but not unlawfully interfered with; The

application of the PSED was deemed irrelevant to the decision

•

Proportionality analysis can include measuring economic benefits to

wider society, in assessing whether a public body has struck the

correct balance against the rights of the individual etc. In conducting

this kind of decision-making process today, in setting a new policy

about the shift to one type of care to another, the Article 8 ECHR rights

of the disabled/unwell/elderly (as groups with 'protected

characteristics') would need to be addressed as part of the process

of having due regard to 'eliminating victimisation' etc.

Introduction

An overview of the paper (2)

•

The particular focus of the paper will be on the notion that

statutory duties to consult, including the PSED, are duties

that raise, augment or supersede the applicable threshold

to meet the requirements of common law procedural

fairness to be met by public bodies;

• while the paper will address the PSED as something which

highlights the importance of this doctrinal development.

R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex

p. Coughlan [2001] QB 213

Consultation principles can be found in the

judgment of Lord Woolf MR... (1 of 2)

“It is common ground that, whether or not consultation of

interested parties and the public is a legal requirement, if it is

embarked upon it must be carried out properly. To be proper,

consultation must be undertaken at a time when proposals

are still at a formative stage; it must include sufficient

reasons for particular proposals to allow those consulted to

give intelligent consideration and an intelligent response;

adequate time must be given for this purpose; and the product

of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account

when the ultimate decision is taken..."

R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex

p. Coughlan [2001] QB 213

Consultation principles can be found in the

judgment of Lord Woolf MR... (2 of 2)

"…It has to be remembered that consultation is not litigation: the

consulting authority is not required to publicise every submission it

receives or (absent some statutory obligation) to disclose all its advice.

Its obligation is to let those who have a potential interest in the subject

matter know in clear terms what the proposal is and exactly why it is

under positive consideration, telling them enough (which may be a

good deal) to enable them to make an intelligent response. The

obligation, although it may be quite onerous, goes no further than this.”

This is the often-cited common law position, but the Supreme

Court noted in Moseley in 2014 that statutory duties to

consult/provide fuller information for consultation make the

Coughlan principles a stricter matter of application.

Statutory duties to consult, as placed on public

bodies - which can form grounds of JR

An example: "arrangements which secure that

users are involved" - S.242 NHS Act 2006

(1B) Each relevant English body must make arrangements, as respects health

services for which it is responsible, which secure that users of those services,

whether directly or through representatives, are involved (whether by being

consulted or provided with information, or in other ways) in–

(a) the planning of the provision of those services,

(b) the development and consideration of proposals for changes in the way

those services are provided, and

(c) decisions to be made by that body affecting the operation of those services.

(1C) Subsection (1B)(b) applies to a proposal only if implementation of the proposal would

have an impact on–

(a) the manner in which the services are delivered to users of those services, or

(b) the range of health services available to those users.

(1D) Subsection (1B)(c) applies to a decision only if implementation of the decision (if

made) would have an impact on–

(a) the manner in which the services are delivered to users of those services, or

(b) the range of health services available to those users.

R (Joicey) v Northumberland County Council

[2014] EWHC 3657 (Admin)

Ultimate quashing of planning permission for a

wind turbine to be built by R & J Barber Farms

Ltd

•

Cranston J: (para. 34) "The Local Government (Access to Information)

Act 1985 inserted a number of right to know provisions as part VA of

the Local Government Act 1972 (“the 1972 Act”)."

•

Cranston J: (para. 47) "Right to know provisions relevant to the taking

of a decision such as those in the 1972 Act and the Council’s

Statement of Community Involvement require timely publication.

Information must be published by the public authority in good

time for members of the public to be able to digest it and make

intelligent representations: cf. R v North and East Devon Health

Authority Ex p. Coughlan [2001] Q.B. 213, [108]; R (on the application

of Moseley) (in substitution of Stirling Deceased) v Haringey LBC

[2014] UKSC 56, [25]. The very purpose of a legal obligation

conferring a right to know is to put members of the public in a

position where they can make sensible contributions to

democratic decision-making."

"The real Article 8 [ECHR] battleground"?

Munby LJ in R. (on the application of Bibi) v

Secretary of State for the Home Department

[2013] EWCA Civ 322

• "Proportionality...

• Wilson

is the real Article 8 battleground."

LJ in R. (on the application of Quila) v Secretary of State for the

Home Department [2011] UKSC 45

• "(a) is the legislative object sufficiently important to justify limiting a

fundamental right?;

• (b) are the measures which have been designed to meet it rationally

connected to it?

• (c) are they no more than necessary to accomplish it? And

• (d) do they strike a fair balance between the rights of the

individual and the interests of the community?”

Proportionality and fact-finding?

Lord Munby (again) in outlining individual

consultation as an element of proportionate

action

• "So

procedural fairness is something mandated not merely by

Article 6, but also by Article 8". Per Munby J (as he then was), Re G

(Care: Challenge to Local Authority’s Decision) [2003] EWHC 551 (FAM)

[34]

• "[There

are] standards of procedural fairness mandated in [certain

circumstances] both by the common law and by Article 8." Per

Munby LJ in R (on the application of H) v A City Council [2011] EWCA

Civ 403, [50–52]

• "Article

8 . . . has an important procedural component." Per Munby

LJ in R (on the application of H) v A City Council [2011] EWCA Civ 403,

[50–52]

Statutory duty to consult on public bodies - the

Public Sector Equality Duty (1 of 2)

s.149 Equality Act 2010 - the PSED

(1) A public authority must, in the exercise of its functions,

have due regard to the need to—

(a) eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and

any other conduct that is prohibited by or under this Act;

(b) advance equality of opportunity between persons who

share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do

not share it;

(c) foster good relations between persons who share a

relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not

share it.

Statutory duties to consult on public bodies the Public Sector Equality Duty (2 of 2)

s.149 Equality Act 2010 - the PSED

(2) A person who is not a public authority but who exercises public

functions must, in the exercise of those functions, have due regard

to the matters mentioned in subsection (1).

(3) Having due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity

between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and

persons who do not share it involves having due regard, in particular,

to the need to—

(a) remove or minimise disadvantages suffered by persons who share

a relevant protected characteristic that are connected to that

characteristic;

(b) take steps to meet the needs of persons who share a relevant

protected characteristic that are different from the needs of persons

who do not share it;

(c) encourage persons who share a relevant protected characteristic to

participate in public life or in any other activity in which

participation by such persons is disproportionately low.

Tom Hickman, 'Too hot, too cold or just right?

The development of the public sector equality

duties in administrative law', P.L. 2013, Apr,

325-344

With regard to the general PSED under s.149 Equality Act

2010:

"It may be that the number of cases has peaked and that

now that a body of case law has developed we will see

fewer reported cases in future years, or at least no further

increase..."

"s.149 of the EA is undoubtedly a candidate for

recognition as constitutionally significant, although the

jurisprudence itself does not yet quite go this far."

"[The uncertainty of a correct granularity of review] is

arguably no more uncertain than what is Wednesbury

unreasonable or what constitutes justification for

overriding a legitimate expectation, or other grounds of

judicial review."

Lord Justice McCombe's 8 points - closure of

the 'Independent Living Fund'

Bracking and others v Secretary of State for

Work and Pensions [2013] EWCA Civ 1345

McCombe LJ laid out a set of points of doctrinal principle around the

PSED, drawing on a range of case law pre- and post-Equality Act

2010, including:

•

•

•

R (Hurley & Moore) v Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills

[2012] EWHC 201 (Admin): Unsuccessful challenge in relation to student tuition

fee increases etc.

R (Diedrick) v Chief Constable of Hampshire Constabulary and the Home

Secretary [2012] EWHC 2144 (Admin): Unsuccessful challenge to the devolution

of discretion in relation to recording ethnicity in police 'stop and accounts' etc.

[NB: PSED-based challenges often brought in conjunction with Article 8

ECHR and Article 14 ECHR grounds etc.]

• Mrs Justice Simler DBE also adopted a 'principles approach' in

setting out the operation of the PSED in 10 points in R (Christian

Kitchen and others) v London Borough of Waltham Forest [2014]

EWHC 1027 (Admin)

Recent judicial recognition of the approach by

McCombe LJ in Bracking

Adopting a standardised view of the 'contents'

of the PSED to have 'due regard'

McCombe LJ set out 8 points in Bracking, drawing substantially on Elias LJ

in Hurley and Moore, that were adopted and utilised/confirmed in at the

following sample of recent cases:

•

•

Hotak v Southwark LBC [2015] UKSC 30; Times, May 25, 2015 (SC)

Lord Neuberger described the list of McCombe LJ's points in Bracking as

'rightly' unchallenged.

•

R. (on the application of A) v Secretary of State for Work and

Pensions [2015] EWHC 159 (Admin) (QBD (Admin))

R. (on the application of Karia) v Leicester City Council

[2014] EWHC 3105 (Admin)

R. (on the application of Aspinall) v Secretary of State for Work and

Pensions [2014] EWHC 4134 (Admin)

R. (on the application of Cushnie) v Secretary of State for Health

[2014] EWHC 3626 (Admin)

R. (on the application of Robson) v Salford City Council [2014]

EWHC 3481 (Admin)

•

•

•

•

Compliance with the PSED: McCombe LJ in

Bracking and Simler J in Christian Kitchen

13 doctrinal points that underpin PSED

grounds for judicial review

(1) Equality duties are an integral and important part of the

mechanisms for ensuring the fulfilment of the aims of antidiscrimination legislation (R (Elias) v Secretary of State for Defence

[2006]). The duty to have 'due regard' to issues of equality (e.g.

equality of opportunity between different groups with or without

'protected characteristics) must be “exercised in substance, with

rigour, and with an open mind”. It is not a question of “ticking boxes”;

while there is no duty to make express reference to the regard paid to

the relevant duty, reference to it and to the relevant criteria reduces the

scope for argument: R (Brown) v Secretary of State for Work and

Pensions [2008].

(2) The duty applies to the exercise of all public authority

functions even where the relevant decision relates to a public

authority’s private law arrangements such as the termination of a

private contract or licence: see for example, Barnsley Borough Council

v Norton [2011] relating to possession proceedings in relation to

residential property.

Compliance with the PSED: McCombe LJ in

Bracking and Simler J in Christian Kitchen

13 doctrinal points that underpin PSED

grounds for judicial review

(3) An important evidential element in the demonstration of the

discharge of the duty is the recording of the steps taken by the

decision maker in seeking to meet the statutory requirements: R

(BAPIO Action Ltd) v Secretary of State for the Home Department

[2007]. It is good practice for a decision maker to keep records

demonstrating consideration of the duty as per R (Brown) v

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2008].

(4) (There is a rebuttable presumption that) the relevant duty is upon

the Minister or other decision maker personally. What matters is what

he or she took into account and what he or she knew. Thus, the

Minister or decision maker cannot be taken to know what his or her

officials know or what may have been in the minds of officials in

proffering their advice - R (National Association of Health Stores) v

Department of Health [2005]. The PSED as a legal duty is nondelegable: R (Brown) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

[2008].

Compliance with the PSED: McCombe LJ in

Bracking and Simler J in Christian Kitchen

13 doctrinal points that underpin PSED

grounds for judicial review

(5) A decision maker must assess the risk and extent of any adverse

impact and the ways in which such risk may be eliminated before the

adoption of a proposed policy and not merely as a “rearguard action”,

following a concluded decision: Kaur & Shah v LB Ealing [2008]. The

duty must be fulfilled before and at the time when a particular

policy is being considered: R (Brown) v Secretary of State for Work

and Pensions [2008].

(6) The public authority decision maker must be aware of the duty to

have “due regard” to the relevant matters; and that the duty is a

continuing one: R (Brown) v Secretary of State for Work and

Pensions [2008].

(7) "General regard to issues of equality is not the same as

having specific regard, by way of conscious approach to the

statutory criteria": R (Meany) v Harlow DC [2009] EWHC.

Compliance with the PSED: McCombe LJ in

Bracking and Simler J in Christian Kitchen

13 doctrinal points that underpin PSED

grounds for judicial review

(8) Those reporting to or advising Ministers/other public authority

decision makers, on matters material to the discharge of the duty, as

officials must not merely tell the Minister/decision maker what

he/she wants to hear but they have to be “rigorous in both enquiring

and reporting to them”: R (Domb) v Hammersmith & Fulham LBC

[2009].

(9) Provided the court is satisfied that there has been a rigorous

consideration of the duty, so that there is a proper appreciation of the

potential impact of the decision on equality objectives and the

desirability of promoting them, it is for the decision maker to decide

how much weight should be given to the various factors

informing the decision: R (Hurley & Moore) v Secretary of State for

Business, Innovation and Skills [2012].

Compliance with the PSED: McCombe LJ in

Bracking and Simler J in Christian Kitchen

13 doctrinal points that underpin PSED

grounds for judicial review

[10] "The concept of ‘due regard’ requires the court to ensure that there has

been a proper and conscientious focus on the statutory criteria, but if that is

done, the court cannot interfere with the decision simply because it would

have given greater weight to the equality implications of the decision than

did the decision maker. In short, the decision maker must be clear

precisely what the equality implications are when he puts them in the

balance, and he must recognise the desirability of achieving them, but

ultimately it is for him to decide what weight they should be given in the light

of all relevant factors": R (Hurley & Moore) v Secretary of State for

Business, Innovation and Skills [2012].

(11) The duty of due regard under the statute requires public authorities to

be properly informed before taking a decision. If the relevant material is

not available, there will be a duty to acquire it and this will frequently

mean that some further consultation with appropriate groups is required: R

(Hurley & Moore) v Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills

[2012].

Compliance with the PSED: McCombe LJ in

Bracking and Simler J in Christian Kitchen

13 doctrinal points that underpin PSED

grounds for judicial review

(12) In a case where large numbers of vulnerable people, very many of

whom fall within one or more of the protected groups, the due regard

necessary is very high: see Harjula v London Councils [2011].

(13) A sense of proportionality and reality is required. If a fair reading of

the equality analysis makes clear that the decision-maker considered

and conscientiously applied his or her mind to the relevant equality

impact or impacts of the proposed decision, the court will not

micromanage such decisions: Branwood v Rochdale Metropolitan

Borough Council [2013].

Tom Hickman, 'Too hot, too cold or just right? The development

of the public sector equality duties in administrative law', P.L.

2013, Apr, 325-344

"It may be that the number of cases has peaked and that now that a body of

case law has developed we will see fewer reported cases in future years, or

at least no further increase..." [JG: Perhaps the PSED will not develop

too much doctrinally in the next five years, but it will increasingly be

drawn on as part of the 'anti-austerity grounds' of JR.]

"s.149 of the EA is undoubtedly a candidate for recognition as

constitutionally significant, although the jurisprudence itself does not yet

quite go this far." [JG: It needs to be, with the HRA under attack?]

"[The uncertainty of a correct granularity of review] is arguably no more

uncertain than what is Wednesbury unreasonable or what constitutes

justification for overriding a legitimate expectation, or other grounds of

judicial review." [JG: Though complex, the PSED is arguably getting

more certain, in the doctrinal sense.]

Stephenson (2014) and Carr (2014) have both been critical of the way

the PSED has been reviewed and critiqued by the Government

Equalities Office in 2013 - who were dismissive of its value.

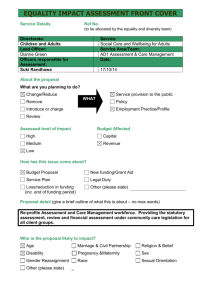

Government Equalities Office, Review of the Public

Sector Equality Duty: Report of the Independent

Steering Group, 6th September 2013, London:

Government Equalities Office

" Although the number of JRs brought under the PSED is low, it is still a

significant proportion of the overall number of JRs and there have been

several high profile cases. In all the cases we have seen, the PSED is

just one of a number of grounds, which suggests that these JRs

would have arisen even in the absence of a PSED...

"While courts have said the duty should not be too burdensome and

completion of an EIA is not a statutory requirement, in the majority of

cases public bodies have nevertheless completed EIAs… Challenges

have been based on the fact that what it means to have “due regard” in a

particular situation is not qualified in the legislation. Only the court can

confirm that a public body has had “due regard” in a particular case…"

(pg.28)

"The Steering Group therefore recommends:

"Enforcement of the PSED needs to be proportionate and

appropriate. In light of the findings around Judicial Review, the

Government should consider whether there are quicker and more costeffective ways of reconciling disputes relating to the PSED." (pg.31)

House of Lords and House of Commons Joint

Committee on Human Rights, The implications for

access to justice of the Government's proposals to

reform judicial review, Thirteenth Report of Session

2013–14

"We welcome the unequivocal confirmation from the Chair of the

Independent Review of the Public Sector Equality Duty (“PSED”) that in

his view the PSED should continue to be legally enforceable. It is clear to

us that the legal enforceability of the PSED is crucial in ensuring the

implementation of, and compliance with, equality law by public

authorities."

"From the examples of actual cases that have been cited to us in

both written and oral evidence, it is clear to us that the legal

enforceability of the PSED is crucial in ensuring the

implementation of, and compliance with, equality law by public

authorities. We do not rule out the possibility of there being a

“quicker” and more “cost-effective” mechanism,

but we recommend that any such mechanism must retain the

ultimate legal enforceability of the duty by judicial review, rather

than be an alternative to it." (p.41-42)

Why could the PSED become even more

crucial than it already is?

An example: R (SG) v Secretary of State for

Work and Pensions [2015] UKSC 16

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child ('the UNCRC'), had been a

ground of challenge to a set of regulations which the Secretary of State had put in place

to reduce the overall welfare and benefits costs to the UK government arising from

housing benefits. SG objected to this as damaging to the interests their children, who

would need to be relocated with their families when they could no longer afford to live in

the same home, with less housing benefit to rely on as a result of the new regulations.

It was argued in the SG case that the relevant regulations, created under the Welfare

Reform Act 2012, had not taken into account a need for compliance with the UNCRC but the majority of the UK Supreme Court held that the rule that the UK courts could not

criticise the interpretation by the UK government of an unincorporated treaty or

convention was a strict one. The challenge on the basis of Article 1 Protocol 1 ECHR

combined with Article 14 EHCR grounds also failed in the majority view of the UKSC.

Would a reduction in the benefits cap survive a proportionality challenge,

after this majority decision in the UKSC in SG? Would the PSED play a

role in further litigation in this area? What does 'due regard' mean here?

References

Supporting literature

•

Tom Hickman, 'Too hot, too cold or just right? The

development of the public sector equality duties in

administrative law', P.L. 2013, Apr, 325-344

• Helen Carr (2014), 'The public sector equality duty – a

mainstay of justice in an age of austerity', Journal of Social

Welfare and Family Law, 36:2, 208-210

• Mary-Ann Stephenson (2014), 'Misrepresentation and

Omission—An Analysis of the Review of the Public Sector

Equality Duty', The Political Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 1,

January–March 2014

Thanks

Do you have any questions?

You can always contact me at: j.grace@shu.ac.uk