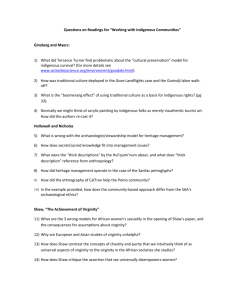

View/Open - University of Limpopo ULSpace Repository Institutional

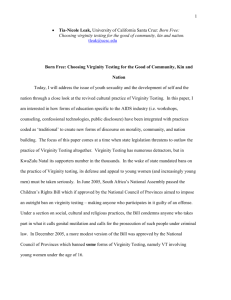

advertisement