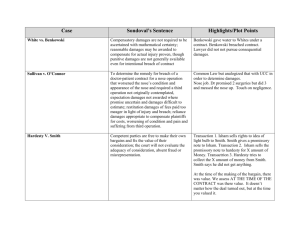

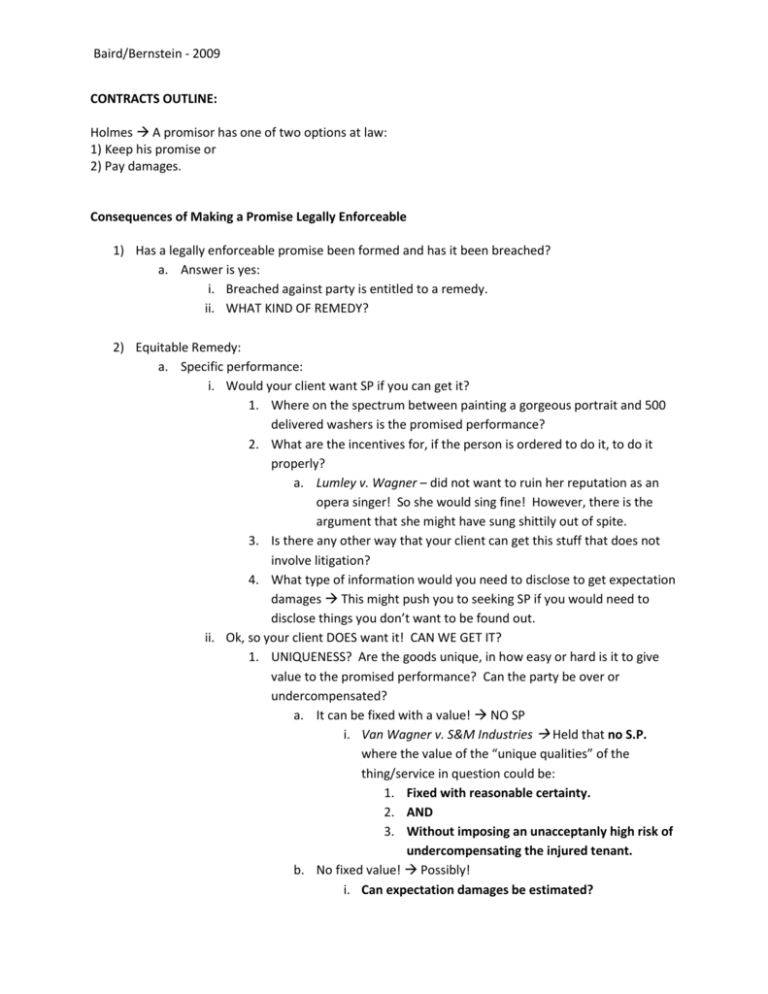

Baird/Bernstein 3 (2009)

advertisement