intergroup contact

advertisement

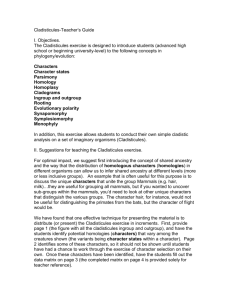

University of Oxford Seminar, University of Helsinki, Finland, May 11, 2012 27/03/2012 2 Outline Impact of diversity: Putnam’s pessimistic prognoses Types of intergroup contact: Whether and how they work Direct and extended forms of contact Impact of contact Focus: generalized/’secondary transfer’ effects Archival re-analysis of contact effects in extreme conditions Rescuers of Jews from Nazi Europe Observational research on intergroup contact Conclusions 2 3 Impact of diversity: Putnam’s pessimistic prognoses Putnam’s (2007) ‘Diversity-Distrust Hypothesis’: Threat vs Opportunity Percentage of Out-groupers + Higher Threat/ Competition + Higher Prejudice = ‘conflict theory’ (Putnam, 2007): “diversity fosters out-group distrust and in-group solidarity” (p. 142) Percentage of Out-groupers + Opportunity for contact + Out-group friends - Lower Prejudice “I think it is fair to say that most (though not all) empirical studies have tended instead to support conflict theory ” (Putnam, 2007, p. 142) 4 5 “In colloquial language, people living in ethnically diverse settings appear to ‘hunker down’ – that is, to pull in like a turtle.” (Putnam, 2007, p. 149) Putnam, R. D. (2007). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30, 137-174. 7 What is the relationship between diversity and trust? Mixed Findings More Diversity Less Trust Putnam (2007); Lancee & Dronkers (2008); Fieldhouse & Cutts (2010) More Diversity More Trust Marschall & Stolle (2004; Black sample); Fieldhouse & Cutts (2010; ethnic minority sample in UK); Morales & Echazarra (forthcoming) More Diversity No effect on Trust Marschall & Stolle (2004; White sample); Gesthuizen, van der Meer & Scheepers (2008); Hooghe et al. (2008) Some Critical Issues in the Putnam Diversity Hypothesis Role of disadvantage Measures of Diversity 8 Index used Level of measured diversity Missing or inappropriate measures of intergroup contact Putnam uses high-threshold measure of contact (friends) Does not test whether contact mediates or moderates diversity effect 8 9 ‘The Contact Hypothesis’ (Allport, 1954) Positive contact with a member of another group (often a negatively stereotyped group) can improve negative attitudes: -- not only towards the specific member, --but also towards the group as a whole 10 Does Contact Work? Results of a ‘Meta–Analysis’ Number of Studies: 515 studies Dates of Studies: 1940s -- 2000 Participants: 250,089 people from 38 nations • Consistent, significant negative effect: more contact, less prejudice The more rigorous the research, the larger the effect (Pettigrew &10Tropp, 2006, 2011) Do We Have Enough Evidence To Challenge Putnam and Impact Policy? Imagine you give evidence to the government on the relevance of your work (e.g., on improving interethnic relations), armed with a data base consisting purely of studies using under-graduates. You are left … exposed! 11 12 Significant Weaknesses of Prior Research on Contact Failure to study contact: (1) over time (2) at the level of the neighbourhood (3) taking account of diversity as well as deprivation (4) using multi-level analysis 13 (PIs: M. Hewstone, A. Heath, C. Peach, S. Spencer; Post docs: A. Al Ramiah, N. Demireva, S. Hussain, K. Schmid) Test of integrated model of group threat theory and contact theory, to examine relationship between macro-level diversity and both individual-level and neighbourhood-level attitudinal outcomes Sampled respondents from neighbourhoods of varying degrees of ethnic diversity Control for additional key macro-level variable: neighbourhood deprivation 14 Between-level neighbourhood measures Percentage Non-White British (range: 1% - 84%) Index of multiple deprivation (IMD; based on variety of indicators, e.g. income, employment, health deprivation) Analysis 14 Data hierarchically ordered in a two-level structure (respondents nested within neighbourhoods) Multilevel structural equation modeling to account for both withinlevel and between-level variance of constructs 15 Overview of research Test of effects of diversity on: Outgroup trust Ingroup trust Neighbourhood trust Focus on key role of intergroup contact 16 Putnam (2007) DIVERSITY + PERCEIVED THREAT – TRUST – Diversity is perceived as threatening and has negative consequences for trust 17 Our Research + DIVERSITY INTERGROUP CONTACT + – PERCEIVED THREAT – TRUST – Diversity offers opportunities for positive contact Positive contact reduces perceived threat Prediction: Diversity will have positive indirect effects on trust 18 Results: White British respondents (N = 868) .55** Intergroup Contact Outgroup Trust –.34*** –.43*** Diversity (Ethnic fractionalization) Perceived Threat –.29*** Ingroup Trust –.30*** –.23** Trust in neighbours Diversity has positive indirect effects on Trust Outgroup Trust (b = .31, z = 2.93, p < .01), Ingroup Trust (b = .21, z = 2.72, p < .01), Neighbourhood Trust (b = .23, z = 2.93, p < .01) 19 Results: Ethnic minority respondents (N = 797) .30** Intergroup Contact .17* Outgroup Trust –.38*** –.30*** Diversity (Herfindahl) .16* Perceived Threat –.31*** .24** Ingroup Trust –.22*** .21** Trust in neighbours Diversity has positive indirect effects on Trust Outgroup Trust (b = .16, z = 2.65, p < .01), Ingroup Trust (b = .16, z = 2.60, p = .01), Neighbourhood Trust (b = .12, z = 2.42, p = .02) 20 Contextual effect of intergroup contact Do individuals from different contexts who have the same amount of intergroup contact differ in their intergroup attitudes? Does the context influence intergroup attitudes over and above individual level variables? If so, then context drives this difference (contextual effect) -- can’t be explained with individual level variables. 21 Contextual effect of intergroup contact Intergroup attitudes (i.e., prejudice) Do individuals from different contexts who have the same amount of intergroup contact differ in their intergroup attitudes? Then context drives this difference (contextual effect) -- can’t be explained with individual level variables. βW Context A βC βB Context B Context C Direct Intergroup Contact Within Group Effect (Level 1): Between Group Effect (Level 2): Contextual Effect: (Extended Contact) e.g., βW = -.30 e.g., βB = -.50 e.g., βC = βB - βW = -.20 22 Results: Leverhulme, UK data Intergroup contact βB = -2.223*** Ingroup Bias Context level Individual level Intergroup contact Contextual Effect: βW = -0.346*** Ingroup Bias βC = βB - βW = -1.877** *controlled for age, sex, education, and IMD 23 Results: Leverhulme, UK data 0.892*** Intergroup contact Tolerant norms -1.840*** βB = -0.614 Ingroup Bias Context level Individual level Intergroup contact Contextual Effect: βW = -0.346*** Ingroup Bias βC = βB - βW = -0.270 Indirect effect on context level: -0.343*** *controlled for age, sex, education, and IMD Results: MPI data, German longit. Data time 1 time 2 Intergroup contact Intergroup contact 24 0.130+ Tolerant norms Tolerant norms -0.318* βB = -0.192** Threat Threat Context level Individual level Intergroup contact Contextual Effect: βW = -0.031* Ingroup Bias βC = βB - βW = -0.161* Indirect effect on context level: -0.041+ *controlled for age, sex, education, and unemployment, and sse rate 25 Putnam’s impact “Will first-hand experience weaken stereotypes? That was the belief of the sociologist Samuel Stouffer, who observed during the Second World War that white soldiers who fought alongside blacks were less racially prejudiced than white soldiers who had not. The political scientist Robert Putnam has stood Stouffer, and Aristotle, on their heads. Putnam has found that first-hand experience of diversity in fact leads people to withdraw from these neighbours” (p. 5) 26 Types of intergroup contact: whether and how they work 27 DIRECT CONTACT Quantity of contact – frequency of interaction with outgroup members, e.g., ‘how often do you meet/talk to/etc. outgroup members where you live/shop/socialize, etc?’ Quality of contact – nature of the interaction with outgroup members, e.g., how positive/negative; friendly/unfriendly, etc, is the contact?’ Cross-group friendship – being friends with outgroup members, e.g., ‘How many close outgroup friends?’ EXTENDED CONTACT Indirect/Vicarious contact, via family or friends, e.g., ‘How many of your family members/friends have outgroup friends? 28 Direct contact: Longitudinal Effects and Evidence of Mediators 29 30 3-Wave Study of Longitudinal Contact in South African ‘Coloured’ Schools (Swart, Hewstone, Christ, & Voci, JPSP, 2011) Age (yrs): Variables: T1: Mean (SD) = 14.68 (1.06) T2 (+ 6 mths): Mean (SD) = 15.31 (1.03) T3 (+ 6 mths): Mean (SD) = 15.67 (1.05) Predictors: cross-group (white) friends Mediators: intergroup anxiety; empathy Outcomes: positive outgroup attitudes; outgroup variability; negative action tendencies 3-wave cross-lagged analyses 3-waves permit mediation analyses Time 1 ‘predictor’ -> Time 2 ‘mediator’ -> Time 3 ‘Outcome’ 31 Outgroup Friendships x1 Outgroup Friendships y1 x2 Intergroup Anxiety x3 x5 y3 Empathy x7 x10 x8 x12 x11 y21 y9 y10 x15 y13 y8 y24 y12 y27 y16 y17 y25 y26 y28 y30 y29 Perceived outgroup Variability y15 y31 Negative Action Tendencies x18 y23 Positive Outgroup Attitudes y11 y14 y22 Empathy Perceived outgroup Variability x14 x17 y5 y7 y20 Intergroup Anxiety Positive Outgroup Attitudes Negative Action Tendencies x16 y4 y6 Perceived outgroup Variability x13 y19 Empathy Positive Outgroup Attitudes x9 y2 Intergroup Anxiety x4 x6 Outgroup Friendships y32 y33 Negative Action Tendencies y18 y34 y35 y36 32 Outgroup Friendships Outgroup Friendships -.14** -.11** Intergroup Anxiety .13** -.14** -.11** Intergroup Anxiety Intergroup Anxiety -.14** -.14** Empathy Outgroup Friendships Empathy .23*** .13** .23*** .23*** Positive Outgroup Attitudes Positive Outgroup Attitudes .15** Perceived outgroup Variability .23*** .15** Negative Action Tendencies Blue: ‘forward’; Red: ‘reverse’ -.27*** -.15** Negative Action Tendencies Positive Outgroup Attitudes Perceived outgroup Variability Perceived outgroup Variability -.15** Empathy -.27*** Negative Action Tendencies 33 Making Sense of ‘Spaghetti’ Green paths are autoregressive. Blue paths are 'forward' paths (as predicted by contact model). Red paths are 'reverse' paths (self-selection). Model equates paths from Wave 1-2, and 2-3 All paths indicated are significant. 34 Outgroup Friendships Outgroup Friendships -.14** -.11** Intergroup Anxiety .13** -.14** -.11** Intergroup Anxiety Intergroup Anxiety -.14** -.14** Empathy Outgroup Friendships Empathy .23*** .13** .23*** .23*** Positive Outgroup Attitudes Positive Outgroup Attitudes .15** Perceived outgroup Variability .23*** .15** Negative Action Tendencies Blue: ‘forward’; Red: ‘reverse’ -.27*** -.15** Negative Action Tendencies Positive Outgroup Attitudes Perceived outgroup Variability Perceived outgroup Variability -.15** Empathy -.27*** Negative Action Tendencies 35 Outgroup Friendships Outgroup Friendships Outgroup Friendships -.14** -.11** Intergroup Anxiety Empathy .13** .23*** -.14** Empathy Positive Outgroup Attitudes Positive Outgroup Attitudes Perceived outgroup Variability Perceived outgroup Variability -.15** Negative Action Tendencies Blue: ‘forward’; Red: ‘reverse’ Intergroup Anxiety Intergroup Anxiety Empathy .23*** .15** Positive Outgroup Attitudes Perceived outgroup Variability -.27*** Negative Action Tendencies Negative Action Tendencies 36 Extended Contact: The Surprising Impact of “weak ties” Some of my friends have friends who are . . . (outgroup members) ‘Extended contact’ is second-hand, rather than involving the participants in direct intergroup contact themselves Just knowing other people in your group who have out-group friends might improve attitudes to the out-group (Wright et al., 1997) 37 38 Extended Contact in Northern Ireland (Results for Catholics and Protestants; N = 316) (Paolini, Hewstone, Cairns & Voci, 2004) .52 Number of Direct Friends -.18*** Prejudice Towards The Group R2 = .48 .79 Intergroup Anxiety R2 = .21 .53*** Number of Indirect Friends .17** - .03 General Group Variability R2 = .11 .89 40 Key facts about extended contact It works by changing group norms It is especially effective for those who have no direct contact It should lead people to take up more opportunities for direct contact in the future Impact of Indirect Contact is Moderated by Amount of Direct (Friendship) Contact (NI- CRU Survey, N=984; Christ, Hewstone et al., PSPB, 2010) When does extended contact work best? When direct contact is low. Low cross-group friendship High cross-group friendship In-group bias 1 0 -1 Low High Indirect contact 41 42 Longitudinal analysis of the effects of extended contact at time 1 on direct contact at time 2 (Swart, Hewstone, Tausch et al., in prep.) .15*** Extended Contact (Time 1) .23*** .21*** Controlling for direct contact scores at Time 1 Neighbourhood Contact Quantity (Time 2) Neighbourhood Contact Quality (Time 2) Contact with Friends (Time 2) An Experimental Comparison of Different Forms of Contact Evidence from Cyprus http://www.isxys.org/isolation/wp-content/uploads/2007/02/turkishpopulation1960-present.jpg 44 Study 1 Participants: 52 female students (26 pairs) at the University of Cyprus Recruitment criteria: Greek/Cypriots Friends with each other Good knowledge of English Study 1: Methodology- Procedure T1 T2 1 WEEK Pre- test (baseline measures) Intervention & Post- test 47 Study 1: Methodology - Contact Intervention Type of Contact – Manipulation of Direct vs Extended contact Randomly allocate one of each pair of participants to each of the two conditions: Direct contact: a 10 minute structured face-to-face interaction of the first member of the pair with a T/C confederate.* Extended contact: the 2nd member of the pair observed her friend interacting with the T/C through a one-way mirror. * the T/C confederate was trained to give the same answers every time. Study 1: Results Direct Contact Mean (SD) Extended contact Mean (SD) Attitudes tow. outgroup member (thermometer) 8.44 (.92) 8.23 (1.31) Typicality of out-group member 2.28 (.89) 2.58 (1.20) In-group (Self) disclosure 3.40 (.76) 3.50 (.81) Out-group disclosure 3.36 (.57) 3.38 (.75) Group Salience 1.97 (.87) 2.26 (1) Contact (State) Anxiety 1.47 (.34) 1.5 (.41) Study 1: Attitudes Results Pre – Post Contact (improved attitudes, esp. Direct contact) 50 Impact of contact 51 Multiple Outcomes of Intergroup Contact 51 Explicit attitudes Attitude strength Implicit attitudes Neural processes Trust Forgiveness Behavioural intentions Outgroup-to-outgroup generalization: the ‘secondary transfer effect’. * Are the effects of contact with members of one group restricted to that outgroup, or do they have ‘knock-on’ or ‘trickle-down’ effects on attitudes towards other groups? Schmid, K., Hewstone, M., Küpper, B., Zick, A., & Wagner, U. (2012). Social Psychology Quarterly, 75, 28–51. 53 Overview Test of secondary transfer effects in cross-national comparison 8 European countries: France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, UK Moderation by Social dominance orientation (SDO)? Ideology of inequality (Pratto, Sidanius et al., 1994) Data from GFE Europe survey (30-minute crosssectional CATI survey) Full sample analysis (N = 7042; Schmid, Hewstone et al., 2012; controls: age, gender, education, income, political orientation ) Low SDO: –.22*** High SDO: –.08ns Negative attitudes – homosexuals –.13*** .37*** Intergroup Contact – Immigrants –.15*** Negative Attitudes – Immigrants .39*** Overall mediation: b = –.06, z = –6.68*** Moderated mediation: Low SDO: b = –.08, z = –6.65*** High SDO: b = –.02, z = –3.14*** Attitudes Jewish 55 Longitudinal Secondary transfer effect in Northern Ireland (N = 181 Catholics, 223 Protestants; matched at T1-T2, 1 year; Tausch et al.,2010) Attitude to ethno-religious outgroup T1 Neighbourhood contact with ethno-religious outgroup T1 Controlling for: Contact with and attitude to racial minorities T1 1.76* Attitude to ethno-religious outgroup T2 .43*** Attitude to racial minorities T2 1.84* 1.07, n.s. Ingroup feeling thermometer T2 * p < .05; ** 56 p < .01; *** p < .001 57 Does contact impact behaviour, and when it really matters?Archival re-analysis of contact effects in extreme conditions: Rescuers of Jews from Nazi Europe Kronenberg & Hewstone (in prep.) 58 Data Data from the Altruistic Personality and Prosocial Behaviour Institute (Oliner/Oliner 1988) 510 respondents from 15 European countries Collected in the 1980s Retrospective case-control sample: Case sample of identified rescuers (N=346, recognized by Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, as ‘Righteous among the Nations’) Control sample matched on age, sex, education, region (N=164) Final sample 412 respondents (297 rescuers, 115 nonrescuers) 59 Main Hypothesis (with multiple controls, e.g. for opportunities to help; pro-social orientation) 59 Pre-war friendships with Jews increase the probability of rescuing Jews (especially Jewish friends) (direct contact via friends) 3. Empirical Application The Impact of Pre-war Friendships with Jews Multinomial logistic regression (variables coded [0,1]): Helping Jewish friends Pre-war frnds. w Jews 12.19** Helping other Jews 2.24** Notes: N = 412. Coefficients are odds ratios. No control variables. + p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. 61 Odds Ratio Odds ratio (OR) calculated shows the probability of helping (Jewish friends; other Jews) vs not-helping OR of 12.19 in previous table 1 means: If you had pre-war Jewish friends, the probability of Helping Jewish Friends divided by the probability of not-Helping was 12.19 times higher than if you did not have prewar Jewish friends. The odds of helping other Jews vs. not helping increase (only) by a factor of 2.24 if respondents had Jewish friends before the war. Less technically: Having Jewish friends before the war made potential rescuers more likely to help, especially to help Jewish friends, but also to help other Jews. 3. Empirical Application The Impact of Pre-war Friendships with Jews: Effect of adding controls Multinomial logistic regression (variables coded [0,1]): Helping Jewish friends Helping other Jews 15.41** 2.89** 1.07** 1.05* Prosocial orientation 18.43** 5.18* Command zone 10.89** 10.36** 0.98 1.19** Pre-war frnds. w Jews Age Size Jewish population Number of rooms 15.28** 12.11** Many neighbours 0.86 0.39* Notes: N = 412. Coefficients are odds ratios. Additional control variables: gender; education level; religiosity; religious confession; SS zone, Jewish Neighbours, partner/children in household, financial resources. + p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Observational research: Is everything for the best in this best of all possible worlds? Limits to the impact of contact: Segregation, desegregation, and re-segregation 64 Cafeteria study in mixed school 64 Coded who sat where and with whom in cafeteria of a 6th Form College (16-18 yrs) in NW England (40% ethnic minority, mostly Pakistani- and Bangladeshi-heritage British Asians) Area A1 Food service counters Costa Area A2 Area A3 Kitchen Day 1 Time 1 Occupied seats 89 Mixed tables 1 Area A4 66 Coding and measures Over a two day period, 3,037 seating positions were coded; we analysed the data using: the segregation index of dissimilarity (D; Clack et al., 2005) Ethnic composition of ‘social units’ Side-by-side and face-to-face cross-race adjacencies (Campbell et al., 1966) Aggregation Index of ethnic clustering (I; difference between actual vs. expected frequency with which Whites and Asians sat opposite each other; Campbell et al., 1966) Asian* White* Black Other Pillar (i.e., not a seat) Empty seat 68 Coded data of 22 time intervals . . . 68 Area A1 Food service counters Costa Area A2 Area A3 Kitchen Day 1 Time 1 Occupied seats 89 Mixed tables 1 Area A4 Area A1 Food service counters Costa Area A2 Area A3 Kitchen Day 1 Time 2 Occupied seats 189 Mixed tables 5 Area A4 Area A1 Food service counters Costa Area A2 Area A3 Kitchen Day 1 Time 6 Occupied seats 295 Mixed tables 11 Area A4 72 Ethnic composition of social units White/ Asian White/ Asian/ Black/ Other White/ Black/ Other Asian/ Black Black/ / Other Other 58.97% 30.91% 4.18% 0.33% 4.73% 0.55% All White % of social units All Asian 0.33% 73 Mean Ethnic Aggregation Indices for each area across both days Day Area No. of Intervals I Upper Limit Lower Limit 1 1 10 -1.99 -0.98 -4.36 1 2 10 -0.71 0 -2.57 1 3 10 -0.29 0 -1.48 1 4 10 -1.09 0 -3.04 2 1 12 -1.6 -0.32 -3.82 2 2 12 -0.39 0 -1.52 2 3 12 -0.44 0 -3.44 2 4 12 -1.19 0 -3.02 Note: I denotes aggregation index (negative values indicate more ethnic clustering/less cross-ethnic mixing than expected from random distribution). See Area 1 . . . Area A1 Food service counters Costa Area A2 Area A3 Kitchen Day 2 Time 7 Occupied seats 142 Mixed tables 4 Area A4 75 The number of Whites versus Asians in each area for both days Day Area No. of intervals Number of Whites Number of Asians 1 1 10 251 366 1 2 10 254 16 1 3 10 141 9 1 4 10 282 46 2 1 12 241 461 2 2 12 278 16 2 3 12 182 13 2 4 12 381 36 76 Lessons from cafeteria study Mixed student body does not equate with intergroup contact Students do, in fact, report contact, including outgroup friends, and contact is associated with more positive attitudes But why do students choose to sit apart at lunch? Does it even matter that they do? Ongoing research 76 77 Conclusions Actual contact is crucial for integration Just ‘living together’ is not enough (re-segregation problem in cafeteria) Contact does mediate impact of neighbourhood diversity; Putnam is too pessimistic Direct and extended and forms of contact have effects Contact has multiple outcomes; STE especially important Effects of contact shown via multi-method approach: Surveys (cross-sect’l. &longitud.); experiments; archival analysis To understand diversity effects you have to study contact. 77 78 Funding Leverhulme Trust Community Relations Unit (N.I.) Economic and Social Research Council Nuffield Foundation Russell Sage Foundation, U.S.A. Templeton Foundation, U.S.A. (ex) Graduate students Maria Ioannou Dr Ananthi al-Ramiah Dr Hermann Swart Dr Nicole Tausch Dr Rhiannon Turner Dr Christiana Vonofakou Research collaborators Prof. Ed Cairns (University of Ulster) Dr Oliver Christ (University of Marburg, Germany) Prof. Joanne Hughes (University of Ulster) Dr Jared Kenworthy (University of Texas) Prof. Clemens Kronenberg (University of Mannheim) Dr Katharina Schmid (University of Oxford) Dr Alberto Voci (University of Padua, Italy) Undergraduate students Eleanor Baker Christina Floe Caroline Povah Elisabeth Reed Anna Westlake 79