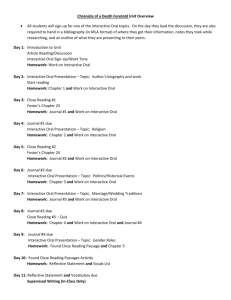

Foster Care Presentation - Jessie's Senior Portfolio

advertisement

Samantha McCartney, Jessie Neel, and Carson Pennypacker Today, youth who age out of the nation’s foster care system are at high risk of having difficulty managing the transition from dependent adolescence to independent adulthood. They experience high rates of educational failure, unemployment, poverty, out-of-wedlock parenting, mental illness, housing instability, and victimization. The government takes children away from their parents under the presumption that the government can provide for them better. The government tries to reunite the youth with their families, but when that isn’t possible they try to find them another permanent home through adoption. At the end of the day it is the government, acting as parents, that decides when foster youth are ready to be on their own. According to estimates from the federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS), 542,000 children lived in outof-home care on September 30, 2001. Of these children, 55% were black and/or Hispanic 52% were male 48% lived with nonrelative foster parents 24% lived in relative foster care 18% lived in group homes 4% in a pre-adoptive home 3% were living at home during a trial home visit 2% had run away from care Child welfare agencies are required to make “reasonable efforts” to prevent placement of children in out-of-home care, usually in the form of social services for their families. If the children and youth cannot return to the care of their families, the child welfare agency and the court attempt to find another permanent home for the child through adoptive or legal guardianship. Wulczyn and Brunner Hislop analyzed placement histories and discharge outcomes of all youth in twelve states. Few youth who age out of care actually grow up in the foster care system. This should not be surprising given that the median age of children entering foster care is less than nine years, and about half of all children leave care within one year of entry. 47% of these youth were returned to their families at discharge from the child welfare system. What responsibility should the child welfare system bear for preparing foster youth for independent living? Former foster youth must face the transition to independence with significant deficits in educational attainment, and they do not appear to make up for these deficits during the transition. These deficits put them at a significant disadvantage in the labor market and are likely to contribute to some of the other negative outcomes they experience. Researchers found that: 66% of the eighteen-year-olds discharged from care in had not graduated from high school Former foster youth suffer from more mental health problems than the general population. They face sexual and physical victimization. 25% of the males and 15% of the females reported experiencing physical victimization Former foster youth experience mental health problems during the transition to adulthood, which raises concerns about their ability to maintain healthy relationships and employment. Not much research has been conducted on substance use among former foster youth, because youth who have serious substance abuse problems may end up moving from the child welfare system into the juvenile corrections system due to behavior associated with their substance abuse before they age out of foster care. 6% of alcoholics reported lived in out-of-home care 39% of those were not clinically diagnosed Former foster youth have a higher rate of involvement with the criminal justice system than the general population. 28% of males and 6% of females from a New Orleans study had been convicted of crime. A criminal record can limit the future employment and housing prospects of these youth. Former foster children tend to have higher rates of marital separation and divorce, lower rates of marital satisfaction, are more likely to remain single, and have higher rates of premarital births than their peers. 31% of former foster children surveyed were single mothers 46% of former foster youth reported having children with higher rates of health, education, and behavior problems than their peers. Many of these former foster youth make for unfavorable marriage partners because of these mental health, education, and behavior problems. Research implies former foster children are less financially independent, depending more on public assistance than their peers. 30% reported having public assistance after leaving care 53% reported having serious money problems after leaving care 1/3 reported doing something illegal to earn money Former foster youth tend to have higher rates of unemployment and lower wages, which eventually results in poverty. Research indicates former foster children have higher rates of mobility, housing instability, and homelessness. 32% surveyed lived in six or more places after being out of foster care for two and a half to four years 25% were homeless for at least one night after leaving care Most research notes former foster youth have higher rates of social isolation and lower rates of civic engagement than their peers. Only 30% of former foster children surveyed indicated belonging to any organization. Do you think former foster care children should keep in touch with their biological parents after they leave foster care? Research suggests former foster youth do keep in touch with their mothers and to their fathers, but to a lesser degree. Research indicates 1/3 – 1/2 of former foster youth keep in touch with their mothers monthly. 88% reported visiting with their siblings at least once after leaving care. Contact with their biological and foster families suggests a source of natural support for former foster youth during their transition into adulthood. 54% of former foster youth reported living with a relative after leaving care. Even though former foster youth may stay in touch with their families, some still report not having a “psychological parent” they can turn to for advice. Children enter foster care because their safety is at risk in their own homes. 1/5 of former foster children suffer from maltreatment, which results in physical and mental health problems, difficulties in forming interpersonal relationships, impaired cognitive development, reduced educational attainment, and increased rates of delinquency. Therefore, children age out of foster care and suffer from pasts of trauma and neglect. The foster care system should protect children from maltreatment and help them from the maltreatment already experienced to improve their transition to adulthood. Research suggests foster care does not have positive or negative effects on children removed from their homes. Because foster care removes children from unsafe homes, it is believed to save children, but when three certain characteristics of foster care are present, foster care can actually have negative effects on children. These three characteristics include placement instability, poor attention to educational needs, and inadequate medical care. Children’s placement numbers predict their readiness to live independently once they are older adolescents. Fewer placements for foster care children are associated with higher rates of life satisfaction, better physical functioning, higher educational attainment, and lower levels of criminal activity. Foster care children enter care behind in educational achievement and never “catch up” while in care. 1/3 of elementary-age foster children and 2/3 of high school-age foster children repeated at least one grade. Because of their frequent placements, special needs in the classroom are unnoticed by teachers, caseworkers, and foster care parents. Foster care children don’t receive adequate medical care, contributing to health problems which continue into emerging adulthood. 78% of foster children are at risk for HIV, but only 9% are tested Since 1961, the federal government has reimbursed the states for the cost of foster care provided to poor children taken from their home by court order 1980s: child welfare advocates started to push for funding to help foster care youth prepare for adulthood 1985: The Independent Living Initiative provided funds to the states to help adolescents develop skills to live on their own Services available to youth ages 16-21 Reauthorized in 1993: Independent Living Program Outreach programs Training in daily living skills Education and employment assistance Counseling Case management ILP can NOT be used for room and board After the creation of the ILP (Independent Living Program) the government did not require a lot of reporting from the states The ILP had “no established method to review the states’ progress in helping youths in the transition from foster care.” 1998: Only about 60% of all eligible youth received some type of independent living service 1999: The FCIA amended Title IV-E to give states more funding and flexibility to help support teens who are transitioning into independent living Doubled independent living services funding up to $140 million per year Allowed states to use up to 30% of these funds for room and board Enabled states to assist 18-21 year olds who have left foster care Permits states to extend Medicaid eligibility An amendment to this law allowed congress to appropriate $60 million per year for education and training vouchers of up to $5000 per year for youth up to 23 years old Under the FCIA, state performance is a much higher priority The department of HHS (Health and Human Services) is required to assess state performance in managing independent living programs, and states are required to collect data on the outcomes 1.5% of funding is set aside for rigorous evaluations of promising independent living programs The program created under the FCIA is called the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program referred to as the Chafee Program Named after John Chafee, a senator who was a legislative advocate for foster youth Independent Living Services No way to categorize all services provided by Independent Living Services Describes a wide range of approaches to meeting the needs of youth who are expected to age out of foster care or who already have By categorizing the services it can give a false impression that programs specialize in only certain areas Public and Private agencies provide multiple services, serve broad populations, and focus on multiple outcomes Life skills training, mentoring programs, transitional housing, health and behavioral services, educational services, and employment services What are some independent living services that you think would help foster care teens transition into adulthood and independence? Life Skills Mentoring Services Probably the most common element of independent living programs Practice skills they will have to master to survive on their own Establish connections between youth and caring adults, and some peer mentorship programs also exist Housing One of the most important areas because youth are responsible for obtaining their own housing The FCIA helped by extending funding for room and board through 21 years old, but the funding isn’t usually enough Educational Services Increase literacy Help teens to start a career path Connect them with educational/vocational programs These services are NOT available to all foster youth 2/5 of eligible foster youth do NOT receive independent living services For those who do receive services, it is unlikely that they receive all available to them Doubled federal funding for independent living services Allowed states to spend some new funds on housing for youth of 18 to 21 years old Federal Reimbursement for costs of Medicaid for former foster youth 18 to 21 years old Advocates for foster youth believe housing is essential for helping youth achieve independence Before FCIA, former youth could only receive Medicaid if they were eligible for other reasons (ex: poor young women with children) New Focus on outcomes and program evaluation FCIA is the first federal child welfare legislation that specifies measure of well-being for the state to monitor $140 million increase is significant, but is only a small amount compared to the population size The FCIA allows states to use the Chafee Program Funds to provide services to those under 16 In September 2001, there were 100,056 youth 16+ in foster care = $1,400 available per year per eligible youth This does not include those who have aged out of care or left foster care There are about 60,000 eligible youth for housing assistance. If the the state spends the maximum 30% of the Chafee Funds on housing, there would be $700 per person to spend. The success of the FCIA in achieving it goals will require more funding that what is provided currently Only a few states have chosen to extend Medicaid eligibility for former foster youth Poor knowledge base supporting independent living services Finding answers to what works in helping foster youth successfully transition to adulthood is hard to find Most important limitation: Target Population Few youth actually age out of foster care Include all foster youth who spent time in foster care after 16 years old ILS rarely reach out to those who leave foster and are discharged to family members Children who run away from foster care are the most at risk of poor adult outcomes This group of teens may be the most help in finding out what is missing from current efforts to help foster teens prepare for independence The lack of the Independent Living Programs to try and reengage runaway youth and of policies to target their needs shows a reluctance to serve the most needy foster youth The adolescent population in the child welfare system is the most needy group on their transition to adulthood These teens are the victims of their own kin The current policy for foster youth is not ideal, and the resources available to these youth are still inadequate There is hope that the current support will lead some states or jurisdictions to set an example for others to follow These examples would hopefully lead to needed changes in our federal policy Want these youth to be treated as “our” children http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.p hp?storyId=125594259