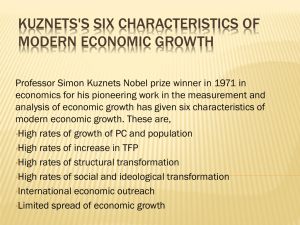

TFP growth

advertisement

Drivers of Developing Asia’s Growth: Past and Future Presented by Donghyun Park, Economics and Research Department, Asian Development Bank (dpark@adb.org), at Research Seminar in Sogang University, Seoul, On 6 October 2010 Prepared jointly by Donghyun Park and Jungsoo Park, Sogang University, Korea, as background paper for Asian Development Outlook (ADO) 2010 Update, Forthcoming as ADB Economics Working Paper Outline 1. Introduction 2 Empirical analysis of growth drivers: pattern of growth in the recent past → relative importance of capital versus TFP 3 Empirical analysis of growth drivers: estimation of per worker GDP growth and TFP growth models 4.Relative Importance of Determinants for per worker GDP growth and TFP growth 5. Priority areas for sustaining growth 6. Concluding observations 2 1 Introduction and motivation: why long-run growth? Developing Asia was recently preoccupied with using fiscal and monetary policy to offset the negative impact of global financial crisis. Theme of ADO 2010 As the crisis recedes, short-run macroeconomic stabilization will give way to long-run growth as the top priority of Asian policymakers. The region has recovered much faster and stronger than expected. Fiscal and monetary stimulus seem to have contributed to the recovery. 3 1 Introduction and motivation: why long-run growth? The key question now becomes – can high growth be sustained beyond the current V-shaped recovery? More importantly, what must the region do to sustain growth in the long run? What are the key obstacles to long-run growth and what are the key policy options for overcoming those obstacles? E.g. weak investment policy measures to improve investment climate High and sustainable long-run growth is indispensable for substantial and sustained poverty reduction. Developing Asia has made substantial progress in reducing poverty but a lot of poverty still remains. The region is home to two-thirds of the world’s poor. 4 1 Introduction and motivation: why long-run growth? The external environment may be less benign in the post-crisis period. Weaker demand from traditional G3 There may be greater volatility. Caveat Robust demand from developing countries will partly offset Industrialized countries are no longer the bedrock of stability that they were before the global crisis. Related to this, is it time to re-think the outward-looking export-led growth model? There is no need for a fundamental re-think openness will continue to yield enormous benefits for the region. But, rebalancing is feasible and desirable (ADO 2009), as is strengthening intra-regional trade (ADO 2009 Update). But long-run growth is determined by supply-side factors rather than demand-side factors. More fundamentally, precisely because of Asia’s spectacular past success and transformation, some policies which worked well in the past will be less effective. Policies that are effective at lower stage of economic development become less effective at a higher stage of economic development. In particular, Asia has been transformed from a capital-scarce region to a capitalabundant region. 5 1 Introduction and motivation: why long-run growth? Another big challenge for the region’s long-run growth is the end of the demographic dividend. Adverse implications for labor supply Adverse implications for savings Productivity growth is likely to play a bigger role in the region’s economic growth. In the past, capital accumulation contributed substantially to the region’s growth. Especially in East Asia high-savings, high-investment paradigm Many economies are maturing and set to experience diminishing marginal returns to capital. Even for poorer, capital-deficient countries, productivity growth magnifies the positive impact of investment on output. 6 1 Introduction and motivation: why long-run growth? Developing Asia has been a high performance, high growth region. The region has outperformed the rest of the world. Many of the region’s strong fundamentals – e.g. openness, macroeconomic discipline – will continue to serve the region well in the post-crisis period. Mapping out the region’s future growth requires an understanding of the region’s past growth. In particular, what have been the drivers of the region’s growth in the past? Has the relative importance of the different drivers changed over time? What does this evolution tell us about what will be the key growth drivers of the future? 7 2 Empirical analysis of growth drivers: pattern of growth in the recent past We perform two types of empirical analysis to explain the region’s growth. In this section, we look at the recent pattern of growth. In the next section, we estimate per worker GDP growth models and TFP growth models. Our examination of the pattern of growth between 1992 and 2007 focuses on 2 key indicators. Total factor productivity (TFP) growth Growth accounting estimates which indicate the relative importance of different growth drivers 8 (2.1) Calculations of TFP growth TFP growth without labor quality adjustment Actual labor shares: compensation of employees/GDP, National Account Labor shares = 0.6 TFP growth with labor quality adjustment Exponential labor quality adjustment 9 (2.2) Growth Accounting Growth accounting for the economic growth of 12 Asian economies and of G-5 economies Growth accounting for 5-year intervals for the period of 1992 – 1997, 1997 – 2002, and 2002 – 2007. Three different versions of TFP growth estimates are given: Two without labor quality adjustment One with labor quality adjustment (human capital consideration) The estimates are averaged into five groups: non-Asian G5, Japan, 4 NIEs (Newly Industrialized Economies: Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan), China, 7 ADEs (Asian Developing Economies: India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam). 10 Contributions of inputs In each table, 5-year average growth rates of output, capital, and labor are shown for each interval Contribution of capital is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the growth in capital Contribution of labor is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the growth in labor Contribution of TFP is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the TFP growth Relative contribution of TFP is the relative portion of output growth that is explained by the TFP growth 11 Table 2-1a. Growth Accounting without labor quality adjustments: labor share = actual, 1992-1997 Period (1992-1997) Growth in : Output Capital Labor C1. labor share = actual Contribution of : Capital Labor TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) lsh1992 labsh1992 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.35% 2.50% 0.50% 1.26% 3.29% 0.61% 6.99% 8.72% 2.14% 9.79% 11.45% 1.17% 5.64% 8.04% 2.33% 1.03% 0.29% 1.04% 1.63% 0.31% -0.68% 4.42% 1.03% 1.55% 5.39% 0.62% 3.78% 5.57% 0.70% -0.63% 44.00% -53.52% 22.18% 38.63% -11.24% 60.00% 60.06% 60.00% 49.12% 60.00% 49.71% 60.00% 52.33% 60.00% 30.06% 12 Table 2-1b. Growth Accounting without labor quality adjustments: labor share = actual, 1997-2002 Period (1997-2002) Growth in Output Capital Labor C1. labor share = actual Contribution of Capital Labor TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) Lsh1997 labsh1997 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.58% 3.23% 0.66% -0.19% 1.59% -0.30% 2.57% 4.95% 1.49% 7.69% 8.74% 0.96% 3.16% 3.92% 2.46% 1.33% 0.38% 0.86% 0.78% -0.15% -0.81% 2.43% 0.75% -0.61% 4.10% 0.51% 3.08% 2.75% 0.76% -0.34% 33.38% 431.85% -23.75% 40.10% -10.71% 60.00% 57.89% 60.00% 50.77% 60.00% 50.20% 60.00% 53.11% 60.00% 30.68% 13 Table 2-1c. Growth Accounting without labor quality adjustments: labor share = actual, 2002-2007 Period (2002-2007) Growth in Output Capital Labor C1. labor share = actual Contribution of Capital Labor TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) Lsh2002 labsh2002 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.32% 2.78% 0.77% 1.73% 1.10% -0.07% 5.48% 3.74% 1.46% 12.20% 10.63% 0.85% 6.58% 4.92% 2.25% 1.16% 0.44% 0.72% 0.55% -0.04% 1.22% 1.84% 0.72% 2.91% 4.98% 0.45% 6.76% 3.44% 0.69% 2.45% 31.06% 70.46% 53.11% 55.44% 37.25% 60.00% 59.05% 60.00% 50.97% 60.00% 51.46% 60.00% 53.11% 60.00% 30.55% 14 Table 2-2a. Growth Accounting without labor quality adjustments: labor share = 0.6, 1992-1997 Period (1992-1997) Growth in : Output Capital Labor C2. labor share=0.6 Contribution of: Capital Labor TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) lsh1992 labsh1992 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.35% 2.50% 0.50% 1.26% 3.29% 0.61% 6.99% 8.72% 2.14% 9.79% 11.45% 1.17% 5.64% 8.04% 2.33% 1.00% 0.30% 1.06% 1.32% 0.37% -0.42% 3.49% 1.28% 2.22% 4.58% 0.70% 4.51% 3.21% 1.40% 1.03% 44.90% -33.20% 31.77% 46.10% 18.26% 60.00% 60.06% 60.00% 49.12% 60.00% 49.71% 60.00% 52.33% 60.00% 30.06% 15 Table 2-2b. Growth Accounting without labor quality adjustments: labor share = 0.6, 1997-2002 Period (1997-2002) Growth in Output Capital Labor C2. labor share=0.6 Contribution of: Capital Labor TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) Lsh1997 labsh1997 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.58% 3.23% 0.66% -0.19% 1.59% -0.30% 2.57% 4.95% 1.49% 7.69% 8.74% 0.96% 3.16% 3.92% 2.46% 1.29% 0.39% 0.90% 0.64% -0.18% -0.65% 1.98% 0.89% -0.30% 3.50% 0.58% 3.62% 1.57% 1.47% 0.12% 34.73% 344.17% -11.74% 47.07% 3.77% 60.00% 57.89% 60.00% 50.77% 60.00% 50.20% 60.00% 53.11% 60.00% 30.68% 16 Table 2-2c. Growth Accounting without labor quality adjustments: labor share = 0.6, 2002-2007 Period (2002-2007) Growth in Output Capital Labor C2. labor share=0.6 Contribution of: Capital Labor TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) Lsh2002 labsh2002 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.32% 2.78% 0.77% 1.73% 1.10% -0.07% 5.48% 3.74% 1.46% 12.20% 10.63% 0.85% 6.58% 4.92% 2.25% 1.11% 0.46% 0.74% 0.44% -0.04% 1.33% 1.49% 0.87% 3.11% 4.25% 0.51% 7.44% 1.97% 1.35% 3.26% 32.10% 77.12% 56.74% 60.96% 49.53% 60.00% 59.05% 60.00% 50.97% 60.00% 51.46% 60.00% 53.11% 60.00% 30.55% 17 Findings: Tables 2-1 and 2-2 Main source of growth The main source of growth was capital stock until 2002. After 2002, the main source of growth has shifted to TFP growth. Throughout whole period, the contribution of labor was minimal for all Asian economies Role of TFP growth The contribution of TFP growth for the Asian economies are lower when actual labor shares are used (since higher weights are applied to capital stock growth which was very high) The relative contribution of TFP was lower than those of the non-Asian G5 till 2002. However, estimates and contributions of TFP growth seem to have increased significantly in the period of 2002 – 2007 for the 4 NIEs and 7 ADEs. The TFP growth estimates for the 11 Asian economies for this sub-period are even higher than those of the non-Asian G5. 18 Findings: Tables 2-1 and 2-2 (cont’d) China The estimates and contribution of China’s TFP growth are strongly positive throughout the whole period, exhibiting a very different pattern compared to those of the Asian economies in a similar developmental stage. 19 Contributions of inputs In each table, 5-year average growth rates of output, capital, and labor are shown for each interval Contribution of capital is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the growth in capital Contribution of labor is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the growth in labor Contribution of labor is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the growth in human capital Contribution of TFP is the percentage point of the output growth that is explained by the TFP growth Relative contribution of TFP is the relative portion of output growth that is explained by the TFP growth 20 Table 2-3a. Growth Accounting with labor quality adjustments: labor share = 0.6, 1992-1997 Period (1992-1997) Growth in : Output Capital Labor Human2 C4. exponential laborquality adjustment Contribution of: Capital Labor Human2 TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) lsh1992 labsh1992 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.35% 2.50% 0.50% 0.88% 1.26% 3.29% 0.61% 0.68% 6.99% 8.72% 2.14% 0.49% 9.79% 11.45% 1.17% 1.00% 5.64% 8.04% 2.33% 0.64% 1.00% 0.30% 0.53% 0.53% 1.32% 0.37% 0.41% -0.83% 3.49% 1.28% 0.29% 1.93% 4.58% 0.70% 0.60% 3.91% 3.21% 1.40% 0.38% 0.65% 22.38% -65.37% 27.60% 39.96% 11.46% 60.00% 60.06% 60.00% 49.12% 60.00% 49.71% 60.00% 52.33% 60.00% 30.06% 21 Table 2-3b. Growth Accounting with labor quality adjustments: labor share = 0.6, 1997-2002 Period (1997-2002) Growth in Output Capital Labor Human2 C4. exponential laborquality adjustment Contribution of: Capital Labor Human2 TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) Lsh1997 labsh1997 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.58% 3.23% 0.66% 0.80% -0.19% 1.59% -0.30% 0.48% 2.57% 4.95% 1.49% 0.67% 7.69% 8.74% 0.96% 0.88% 3.16% 3.92% 2.46% 0.71% 1.29% 0.39% 0.48% 0.41% 0.64% -0.18% 0.29% -0.94% 1.98% 0.89% 0.40% -0.71% 3.50% 0.58% 0.53% 3.09% 1.57% 1.47% 0.43% -0.31% 16.06% 496.47% -27.41% 40.19% -9.78% 60.00% 57.89% 60.00% 50.77% 60.00% 50.20% 60.00% 53.11% 60.00% 30.68% 22 Table 2-3c. Growth Accounting with labor quality adjustments: labor share = 0.6, 2002-2007 Period (2002-2007) Growth in Output Capital Labor Human2 C4. exponential laborquality adjustment Contribution of: Capital Labor Human2 TFP (Relative contribution of TFP) Lsh2002 labsh2002 non-Asian G5 Japan 4 NIEs China 7 ADEs 2.32% 2.78% 0.77% 0.47% 1.73% 1.10% -0.07% 0.45% 5.48% 3.74% 1.46% 0.82% 12.20% 10.63% 0.85% 0.72% 6.58% 4.92% 2.25% 0.84% 1.11% 0.46% 0.28% 0.45% 0.44% -0.04% 0.27% 1.06% 1.49% 0.87% 0.49% 2.60% 4.25% 0.51% 0.43% 7.01% 1.97% 1.35% 0.51% 2.74% 19.53% 61.55% 47.47% 57.45% 41.62% 60.00% 59.05% 60.00% 50.97% 60.00% 51.46% 60.00% 53.11% 60.00% 30.55% 23 Findings: Table 2-3 Main source of growth The main source of growth was capital stock until 2002. After 2002, the main source of growth has shifted to TFP growth. Throughout whole period, the contribution of labor was minimal for all Asian economies Growths in human capital for 4 NIEs were lower than the G5 until 2002, but turned higher afterwards. As for the 7 ADEs, the growth in human capital was higher than all other groups(except for China) for all periods. (see human2) 24 Findings: Table 2-3 (cont’d) Role of TFP growth As for the 4 NIEs, the relative contribution of TFP growth was sizeable in the 1992 – 1997 period, but dropped during the post-crisis period of 1997 – 2002. However, the absolute size and relative contribution of TFP became dominant after 2002. As for the 7 ADEs, the TFP growth either negative or minimal till 2002. Just as in 4 NIEs, the growth in TFP became a dominant factor in growth after 2002. The estimates and contributions of TFP growth seem to have increased significantly in the period of 2002 – 2007 for the 4 NIEs and 7 ADEs. The TFP growth estimates for the 11 Asian economies for this sub-period are even higher than those of the non-Asian G5. China The estimates and contribution of China’s TFP growth are strongly positive throughout the whole period, exhibiting a very different pattern compared to those of the Asian economies in a similar developmental stage. 25 3 Empirical analysis of growth drivers: estimation of per worker GDP growth and TFP growth models In the previous section, we analyzed drivers of growth by estimating per worker GDP growth and TFP growth models In this section, we explain per worker GDP growth and TFP growth through various fundamental determinants of growth. The fundamental determinants include capital, human capital, initial per capita GDP relative to US, openness, government effectiveness, geography, population, life expectancy, inflation rate, current account balance. The regression results can inform us about the relative importance of different determinants in driving Asia’s growth in the past. 26 (3.1) Literature on the determinants of GDP and TFP growth Bosworth and Collins (2003) empirical results in identifying sources of labor productivity growth and TFP growth based on international country-level panel data set. Catch-up effect, openness, geographical factors, and institutional quality are shown to be influential in the empirical results on TFP growth equation estimations. Human capital As a factor of growth: Benhabib and Spiegel (1994) or Pritchett (2001). ‘Level of human capital’ influencing productivity growth: endogenous growth literature. Benhabib and Spiegel (1994), Dinopoulos and Thompson (2000), and Bils and Klenow (2000) 27 (3.2) Baseline model and Estimation methods Two-input production function with Cobb-Douglas technology and with constant returns to scale. (h = exp(0.08*edu)) Technology dynamics, Bosworth and Collins (2003) Human capital is therefore affecting the output through two channels. It enters as a factor of input on one hand and also enters as an additional factor that contributes to the growth in the technological level on the other. Empirical equation with human capital consideration as a baseline model equation. 28 (3.2) Baseline model and Estimation methods (cont’d) A ‘five-year interval’ data set which consists of average values or initial values of variables from each non-overlapping five-year intervals within the full sample Initial values of each respective interval are considered for the variables representing initial conditions such as initial income per capita relative to the U.S. level, initial life expectancy relative to the U.S., and initial population. Panel regression with time-fixed effect is performed on the five-year interval panel data set. 29 (3.3) Data Description and Construction of Variables Data Sources GDP, workers: Penn World Tables (PWT version 6.3) Capital stock series are estimated from investment series from PWT based on a perpetual inventory method. Human capital series are education attainment data from Barro and Lee (2010). Since the data set only provides values for every 5 years, the data are interpolated to fill in the intervening missing values. Labor shares are assumed to be 0.6 WDI, WGI (World Bank) 30 (3.4) Empirical results In this section, we report and discuss the key findings from our per worker GDP growth and TFP growth regressions. Furthermore, we include interaction dummies to compare the effect of some variables in Asian countries versus other countries. Above all, the results can inform us about the relative importance of the different determinants – e.g. physical capital and human capital – in driving developing Asia’s growth. 31 <Table 3-1> Per worker GDP growth regressions: five-year average growth (dependent variable = dln(Y/L)): baseline models VARIABLES mdkkl lny_us lnlifes mhuman lnpop mtropic mopenc minflat_cpi mca_gdp mgoveff Observations Adjusted R-squared (1) a1 (2) a2 (3) a3 (4) a4 (5) a5 (6) a6 0.448*** 0.428*** (12.23) (11.26) -0.010*** -0.010*** (-5.186) (-5.396) 0.428*** 0.429*** 0.403*** 0.404*** (11.23) (11.08) (10.06) (10.14) -0.010*** -0.010*** -0.014*** -0.013*** (-4.749) (-4.231) (-4.748) (-5.040) -0.000 -0.001 0.005 (-0.00995) (-0.0634) (0.440) 0.004*** 0.004*** 0.004*** 0.004*** 0.004*** 0.004*** (5.030) (5.158) (5.028) (4.811) (4.498) (4.764) 0.002* 0.002* 0.002* 0.002 0.002* (1.855) (1.813) (1.788) (1.590) (1.787) -0.010*** -0.009*** -0.009*** -0.009*** -0.008** -0.008** (-2.910) (-2.836) (-2.808) (-2.850) (-2.385) (-2.449) 0.005** 0.009*** 0.009*** 0.009*** 0.008** 0.008** (2.134) (2.817) (2.754) (2.834) (2.453) (2.533) 0.000 0.000 (1.007) (1.228) -0.000 -0.000 -0.000 (-0.158) (-0.00117) (-0.0113) 0.006** 0.005** (2.271) (2.109) 315 0.450 315 0.455 315 0.453 315 0.451 315 0.459 315 32 0.459 Findings: Per worker GDP growth regressions (baseline model) Table 3-1 In full sample regressions, following results were robust. Growth in capital stock per worker, population size, human capital, openness, government effectiveness positively contributed to the growth in GDP per worker Lower the initial per capita GDP relative to the US, the less the tropical area, the growth in GDP per worker were higher There is evidence of convergence (catch-up effect) Variables that were not significant were Life expectancy, inflation rate, current account balance relative to GDP 33 <Table 3-2> Per worker GDP growth regression: five-year average growth (dependent variable = dln(Y/L)): governance index VARIABLES mdkkl lny_us mhuman lnpop mtropic mopenc mgoveff (3) a3 (4) a4 (5) a5 (6) a6 0.404*** (10.25) -0.013*** (-5.559) 0.004*** (4.935) 0.002* (1.798) -0.008** (-2.456) 0.008** (2.573) 0.005** (2.118) 0.410*** (10.56) -0.013*** (-5.470) 0.004*** (5.015) 0.002* (1.896) -0.008** (-2.249) 0.007** (2.464) 0.400*** (10.00) -0.013*** (-5.496) 0.004*** (4.748) 0.002 (1.549) -0.008** (-2.285) 0.007** (2.248) 0.005 (0.912) 0.001 (0.151) 0.386*** (9.594) -0.014*** (-5.925) 0.004*** (5.087) 0.002 (1.557) -0.009*** (-2.740) 0.005 (1.496) 0.010*** (2.605) mcontrolcorr 0.004* (1.912) mgoveff_a 0.004 (0.720) -0.007* (-1.896) mgoveff_o Observations Adjusted R-squared 315 0.461 309 0.446 309 0.446 315 0.469 34 Findings: Per worker GDP growth regressions (various governance indicators) Table 3-2 4 different measures of governance indicators (rule of law, government effectiveness, control of corruption, regulatory quality) government effectiveness and control of corruption were shown to be significant in the regression The model (6) includes interaction dummies : mgoveff_a = mgoveff * dummy_asia12 mgoveff_o = mgoveff * dummy_oecd In model (6) the coefficient for the mgoveff rises and the coefficient for interaction term with OECD dummy is significantly negative. => this implies that the government effectiveness was more important in GDP growth per worker for the non-OECD economies (developing economies) 35 (3.3) TFP Growth Regression Empirical equation with human capital consideration as a baseline model equation. 36 <Table 3-3> TFP growth regressions: five-year average growth (dependent variable = dln(TFP)): baseline models VARIABLES lny_us (1) a1 (2) a2 -0.010*** -0.014*** (-5.536) (-5.895) lnlifes mhuman 0.004*** (5.291) 0.004*** (5.045) lnpop mtropic mopenc -0.011*** -0.009*** (-3.325) (-2.849) 0.006** 0.005** (2.346) (2.048) (3) a3 (4) a4 (5) a5 -0.015*** (-5.373) 0.005 (0.429) 0.004*** (4.860) 0.001 (1.163) -0.009*** (-2.676) 0.007** (2.248) -0.014*** (-4.882) 0.005 (0.396) 0.004*** (4.645) 0.001 (1.142) -0.009*** (-2.703) 0.007** (2.338) 0.000 (1.011) -0.000 (-0.207) 0.006** (2.342) -0.012*** (-4.282) -0.009 (-0.693) 0.004*** (4.975) 0.002 (1.603) -0.009*** (-2.662) 0.008** (2.537) 0.000 (0.829) -0.000 (-0.237) minflat_cpi mca_gdp mgoveff 0.006** (2.414) 0.006** (2.288) mcontrolcorr Observations Adjusted R-squared 0.004** (1.994) 315 0.186 315 0.199 315 0.198 315 0.196 309 0.183 37 Findings: TFP growth regressions (baseline model) Table 3-3 In full sample regressions, following results were robust. Human capital, openness, government effectiveness positively contributed to the TFP growth Lower the initial per capita GDP relative to the US, the less the tropical area, the TFP growth Variables that were not significant were Life expectancy, population size, inflation rate, current account balance relative to GDP 38 <Table 3-4> TFP growth regressions: five-year average growth (dependent variable = dln(TFP)): differential effects VARIABLES lny_us mhuman mhuman_a mhuman_o mtropic mopenc (1) a1 (2) a2 -0.014*** -0.014*** (-5.895) (-6.036) 0.004*** 0.004*** (5.045) (5.141) 0.001* (1.822) -0.000 (-0.592) -0.009*** -0.011*** (-2.849) (-3.235) 0.005** 0.004 (2.048) (1.400) mopenc_a mopenc_o mgoveff mgoveff_a mgoveff_o 0.006** (2.414) 0.006** (2.249) (3) a3 (4) a4 (5) a5 -0.014*** (-6.071) 0.004*** (5.267) -0.015*** (-6.198) 0.004*** (5.219) -0.011*** (-3.281) 0.004 (1.444) 0.002** (2.299) -0.000 (-0.152) 0.005** (1.986) -0.011*** (-3.120) 0.003 (0.979) -0.015*** (-6.432) 0.005*** (5.217) -0.003 (-1.205) -0.001 (-0.743) -0.011*** (-2.992) 0.001 (0.295) 0.006 (1.640) 0.004 (1.193) 0.008** (2.284) 0.005 (0.833) -0.007 (-1.415) 0.009*** (2.716) 0.004 (0.816) -0.006* (-1.817) 39 Findings: TFP growth regressions (differential region effects) Table 3-4 Differential impact in three different groups of countries (OECD, 12 Asian, the rest of the world) The model (2) includes interaction dummies : mhuman_a = mhuman * dummy_asia12 mhuman_o = mhuman * dummy_oecd The model (3) includes interaction dummies : mopenc_a = mopenc * dummy_asia12 mopenc_o = mopenc * dummy_oecd The model (4) includes interaction dummies : mgoveff_a = mgoveff * dummy_asia12 mgoveff_o = mgoveff * dummy_oecd 40 Findings: TFP growth regressions (differential region effects, cont’d) Table 3-4 Differential impact in three different groups of countries (OECD, 12 Asian, the rest of the world) The model (2) includes interaction dummies : The role of human capital is greater in the 12 Asian economies than other countries. The model (3) includes interaction dummies : The role of openness is greater in the 12 Asian economies than other countries. The model (4) includes interaction dummies : The role of government effective is greater for the non-OECD economies compared to the OECD economies. 41 4.Relative Importance of Determinants for Per Worker GDP Growth To measure the relative importance of the identified determinants contributing to per worker GDP growth. We use the coefficient estimates of model (3) of Table 3-2 to calculate the contributions of determinants in the per worker GDP growth. 42 Calculation of Contribution Contribution of each factor is obtained from the following calculation (1) calculate the predicted growth in GDP per worker for each country (2) take the difference between the predicted growth in GDP per worker for each country and global average of the predicted growth in GDP per worker (predicted dln(Y/L) of country j – global average of predicted dln(Y/L)) (3) take the difference between each regressor for each country and global average of the respective regressor (Xi of country j – global average of Xi) (4) the differenced values (which is the gap in value from the global average) are multiplied to the corresponding coefficient estimates of model (3) of Table 2. The resulting values are presented in the table in bold figures. 43 How to interpret the results How to interpret the results As for the dep. Var. “predicted growth gap in GDP per worker (gap from the global average)” : this is how much the predicted value of dln(Y/L) is off from the global average of dln(Y/L). For each group, how each group performed relative to the global average. For example, for OECD during 1992 – 1997, in terms of GDP per worker, OECD grew 0.65 percentage point higher than the global average. As for the regressors: Of this gap in growth, catch-up effect contributed -2.16 percentage point (since the initial per capita income level is higher than the global average), human capital contributed 1.02 percentage point (since the human capital is higher than the global average), etc. 44 Table 3-6a. Relative Importance of Determinants for per Worker GDP Growth :1992 - 1997 Groups of countries: OECD 4 NIEs China Other 4 ASEAN 3 ADEs Developing Economies 1992-1997 dependent var growth in GDP per worker predicted growth in GDP per worker predicted growth gap in GDP per worker (gap from the global average) regressors catch-up effect log of population human capital effect geographical effect openness effect government effectiveness 1.86% 4.85% 8.63% 3.56% 2.99% 0.21% 2.15% 4.05% 7.02% 3.52% 3.16% 0.92% 0.65% 2.55% 5.52% 2.02% 1.66% -0.58% -2.16% 0.58% 1.02% 0.39% -0.46% 1.06% -1.83% 1.08% 0.18% 1.08% 0.82% -0.23% -0.08% 0.37% 0.56% -0.40% 0.86% 0.07% -0.06% 0.50% -0.12% -0.41% 0.15% 0.18% 1.16% 0.73% -1.13% -0.01% -0.52% -0.16% 0.41% -0.08% -0.28% -0.08% 0.02% -0.20% 45 Table 3-6b. Relative Importance of Determinants for per Worker GDP Growth :1997 - 2002 Groups of countries: OECD 4 NIEs China Other 4 ASEAN 3 ADEs Developing Economies 1997-2002 dependent var growth in GDP per worker predicted growth in GDP per worker predicted growth gap in GDP per worker (gap from the global average) regressors catch-up effect log of population human capital effect geographical effect openness effect government effectiveness 1.92% 1.08% 6.73% -0.33% 2.09% 1.14% 2.05% 1.99% 5.02% 0.46% 2.10% 0.60% 1.02% 0.96% 3.99% -0.57% 1.07% -0.43% -2.17% 0.57% 1.13% 0.39% -0.40% 0.92% -2.06% 0.57% 0.18% 1.08% 0.81% -0.10% -0.08% 0.37% 0.57% -0.51% 0.60% -0.08% -0.25% 0.50% -0.11% -0.41% 0.31% -0.01% 1.03% 0.73% -1.10% -0.01% -0.46% -0.23% 0.40% -0.08% -0.29% -0.08% 0.00% -0.17% 46 Table 3-6c. Relative Importance of Determinants for per Worker GDP Growth :2002 - 2007 Groups of countries: OECD 4 NIEs China Other 4 ASEAN 3 ADEs Developing Economies 2002-2007 dependent var growth in GDP per worker predicted growth in GDP per worker predicted growth gap in GDP per worker (gap from the global average) regressors catch-up effect log of population human capital effect geographical effect openness effect government effectiveness 1.55% 4.02% 11.35% 3.90% 4.90% 2.47% 3.01% 3.16% 7.20% 2.41% 4.15% 2.61% 0.19% 0.33% 4.37% -0.41% 1.32% -0.21% -2.20% 0.56% 1.14% 0.39% -0.42% 0.88% -2.02% 0.25% 0.17% 1.07% 0.88% -0.05% -0.08% 0.37% 0.66% -0.23% 0.78% 0.01% -0.14% 0.51% -0.05% -0.41% 0.23% 0.09% 0.98% 0.74% -1.00% -0.01% -0.28% -0.17% 0.41% -0.08% -0.29% -0.08% -0.01% -0.18% 47 Findings: per worker GDP growth (comparison across groups) Growth in GDP per worker For the period of 1992 – 1997 and 2002 – 2007, 12 Asian economies grew much faster than the OECD and other developing economies. Growth in 2002 – 2007 are significantly higher relative to those of the 1992 – 1997 period for China, 4 ASEAN, 3 ADEs, but lower for 4 NIEs and OECD. As for the 1997 – 2002 period, the Asian economies slowed down in growth while OECD and other developing economies were relatively unaffected 48 Findings: per worker GDP growth (comparison across groups, 1992 – 1997) Comparisons of the contribution of regressors across groups in 1992 – 1997 Relative income level OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > Other developing economies > China > 3 ADEs. Human capital OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > Other developing economies > 3 ADEs. Government effectiveness OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > 3 ADEs > Other developing economies. Openness 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > Other developing economies > China > OECD > 3 ADEs. 49 Findings: per worker GDP growth (comparison across groups, 2002 – 2007) Comparisons of the contribution of regressors across groups in 2002 – 2007 (changes relative to 1992 – 1997 is in red) Relative income level OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > Other developing economies > 3 ADEs. Human capital OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > Other developing economies > 3 ADEs. Government effectiveness OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > 3 ADEs > Other developing economies. Openness 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > Other developing economies > China > 3 ADEs > OECD. 50 Findings: per worker GDP growth (comparison across time) Compare across time (comparison between 1992 – 1997 and 2002 – 2007 periods) As for 4 NIEs Catch-up effect became significantly more negative as the relative income has risen compared to the global average ( - 1.83 to – 2.02 ) Contribution of human capital increased slightly (0.82 to 0.88), whereas contribution of openness has risen significantly (0.56 to 0.66). Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has reduced (0.86 to 0.78) As for 4 ASEANs Catch-up effect became more negative as the relative income has risen compared to the global average (-0.06 to -0.14) Contribution of human capital (-0.12 to -0.05) and openness (0.15 to 0.23) have risen moderately Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has fallen (0.18 to 0.09) 51 Findings: per worker GDP growth (comparison across time) Compare across time (comparison between 1992 – 1997 and 2002 – 2007 periods) As for 3 ADEs Catch-up effect has fallen as the relative income has risen compared to the global average (1.16 to 0.98) Contribution of human capital (-1.13 to -1.00) and openness (-0.52 to -0.28) have risen significantly Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has not changed. As for China Catch-up effect has fallen as the relative income has risen compared to the global average (1.08 to 0.25) Contribution of human capital (-0.23 to -0.05) and openness (-0.40 to -0.23) have risen significantly Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has fallen mildly (0.07 to 0.01) 52 4.Relative Importance of Determinants for TFP Growth To measure the relative importance of the identified determinants contributing to TFP growth. We use the coefficient estimates of model (2) of Table 3-3 to calculate the contributions of determinants in the TFP growth. 53 Table 3-7a. Relative Importance of Determinants for TFP Growth :1992 - 1997 Groups of countries: OECD 4 NIEs China Other 4 ASEAN 3 ADEs Developing Economies 1992-1997 dependent var growth in TFP predicted growth in TFP predicted growth gap in TFP (gap from the global average) Regressors catch-up effect human capital effect geographical effect openness effect government effectiveness 0.43% 1.88% 3.80% 0.71% 0.39% -0.81% 0.75% 0.77% 1.77% 0.26% 0.14% 0.30% 0.25% 0.27% 1.27% -0.25% -0.36% -0.20% -2.27% 1.06% 0.46% -0.31% 1.17% -1.92% 1.13% 0.85% -0.24% -0.10% 0.43% 0.37% -0.27% 0.94% 0.08% -0.06% -0.12% -0.49% 0.10% 0.20% 1.22% -1.17% -0.01% -0.35% -0.18% 0.43% -0.29% -0.09% 0.01% -0.22% 54 Table 3-7b. Relative Importance of Determinants for TFP Growth :1997 - 2002 Groups of countries: OECD 4 NIEs China Other 4 ASEAN 3 ADEs Developing Economies 1997-2002 dependent var growth in TFP predicted growth in TFP predicted growth gap in TFP (gap from the global average) Regressors catch-up effect human capital effect geographical effect openness effect government effectiveness 0.33% -0.78% 2.99% -0.65% -0.04% 0.15% 0.46% -0.02% 0.85% -0.30% -0.27% 0.22% 0.15% -0.32% 0.55% -0.60% -0.57% -0.08% -2.17% 0.60% 0.84% -0.11% -0.10% 0.43% 0.38% -0.34% 0.67% -0.09% -0.26% -0.11% -0.49% 0.21% -0.01% 1.09% -1.14% -0.01% -0.31% -0.25% 0.42% -0.30% -0.09% 0.00% -0.19% -2.28% 1.17% 0.46% -0.27% 1.01% 55 Table 3-7c. Relative Importance of Determinants for TFP Growth :2002 - 2007 Groups of countries: OECD 4 NIEs China Other 4 ASEAN 3 ADEs Developing Economies 2002-2007 dependent var growth in TFP predicted growth in TFP predicted growth gap in TFP (gap from the global average) Regressors catch-up effect human capital effect geographical effect openness effect government effectiveness 0.40% 2.51% 6.93% 2.96% 2.22% 0.53% 1.62% 1.59% 2.09% 1.16% 1.20% 1.46% 0.07% 0.04% 0.54% -0.39% -0.35% -0.09% -2.31% 1.18% 0.46% -0.28% 0.97% -2.12% 0.26% 0.91% -0.05% -0.10% 0.44% 0.44% -0.15% 0.86% 0.01% -0.15% -0.05% -0.48% 0.15% 0.10% 1.03% -1.04% -0.01% -0.18% -0.19% 0.43% -0.30% -0.09% 0.00% -0.20% 56 Findings: TFP growth (comparison across groups) Growth in TFP For the period of 1992 – 1997 and 2002 – 2007, 12 Asian economies grew much faster than the OECD and other developing economies. TFP growths for all 12 Asian economies in 2002 – 2007 are significantly higher than those of the 1992 – 1997 period. As for the 1997 – 2002 period, the Asian economies slowed down in TFP growth while OECD and other developing economies were relatively unaffected As for the comparisons of the regressors across groups, they are the same as in Table 3-6 57 Findings: TFP growth (comparison across groups, 1992 – 1997) Comparisons of the contribution of regressors across groups in 1992 – 1997 Relative income level OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > Other developing economies > China > 3 ADEs. Human capital OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > Other developing economies > 3 ADEs. Government effectiveness OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > 3 ADEs > Other developing economies. Openness 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > Other developing economies > China > OECD > 3 ADEs. 58 Findings: TFP growth (comparison across groups, 2002 – 2007) Comparisons of the contribution of regressors across groups in 2002 – 2007 (changes relative to 1992 – 1997 are in red) Relative income level OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > Other developing economies > 3 ADEs. Human capital OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > Other developing economies > 3 ADEs. Government effectiveness OECD> 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > China > 3 ADEs > Other developing economies. Openness 4 NIEs > 4 ASEAN > Other developing economies > China > 3 ADEs > OECD. 59 Findings: TFP growth (comparison across time) Compare across time (comparison between 1992 – 1997 and 2002 – 2007 periods) As for 4 NIEs Catch-up effect became significantly more negative as the relative income has risen significantly compared to the global average ( - 1.92 to – 2.12 ) Contribution of human capital (0.85 to 0.91) and of openness has risen moderately (0.37 to 0.44). Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has reduced (0.94 to 0.86) As for 4 ASEANs Catch-up effect became more negative as the relative income has risen compared to the global average (-0.06 to -0.15) Contribution of human capital (-0.12 to -0.05) and openness (0.10 to 0.15) have risen moderately Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has fallen (0.20 to 0.10) 60 Findings: TFP growth (comparison across time) Compare across time (comparison between 1992 – 1997 and 2002 – 2007 periods) As for 3 ADEs Catch-up effect has fallen significantly as the relative income has risen compared to the global average (1.22 to 1.03) Contribution of human capital (-1.17 to -1.04) and openness (-0.35 to 0.18) have risen significantly Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has not changed. As for China Catch-up effect has fallen significantly as the relative income has risen compared to the global average (1.13 to 0.26) Contribution of human capital (-0.24 to -0.05) and openness (-0.27 to 0.15) have risen significantly Effectiveness of government relative to the global average has fallen mildly (0.08 to 0.01) 61 5 Priority areas for sustaining growth The empirical analysis of the previous two section confirms the importance of supply-side factors in sustaining growth. In particular, given the growing importance of TFP growth in the region’s recent economic growth, the key to sustain growth lies in fostering productivity. In the context of developing Asia, four areas – infrastructure, human capital, financial development and trade – will be pivotal to promoting TFP growth. 62 5 Priority areas: Human capital The region’s rapid demographic transition means the end of the demographic dividend in the near future. Caveat – different countries are at different stages of the demographic transition. Therefore, the region’s growth will have to be based on better rather than more workers. The empirical analysis of this paper supports this point – i.e. small contribution of labor to growth and significance of human capital in TFP growth. The region’s education systems have to do a much better job of producing workers with the “right” skills It is true that the region has invested heavily in education. However, much of this investment is wasted and misallocated. 63 5 Priority areas: Trade Trade and more generally, openness, will continue to be a key growth driver for the region, but intra-regional trade may grow in significance. This reflects the rising income levels and purchasing power of the region, and the relative decline of G3. Trade delivers substantial dynamic efficiency and productivity benefits by forcing firms and industries to raise their game to survive foreign competition. The empirical analysis of this paper supports this point – the significance of openness for TFP growth. Regional integration which moves countries toward a single market will further expand such dynamic gains. 64 5 Priority areas: Infrastructure Infrastructure such as better transportation and communication networks improves the productivity of all firms and industries. Therefore, good infrastructure also raises the returns to private-sector investment. A large part of developing Asia still suffers from serious infrastructure deficit. A long-standing barrier to India’s growth is its inadequate infrastructure. Even in PRC, the interior provinces need more and better infrastructure. There is a lot of scope for regional cooperation and integration in infrastructure in the provision of infrastructure. E.g. Bhutanese energy for India 65 5 Priority areas: Financial development Investment will continue to be a key growth driver for the region but efficiency of investment will matter more. Therefore, the region’s sound and efficient financial systems that allocate capital to its most productive uses. The region has made great strides in financial development since the Asian crisis but there is still a lot of scope for improvement. The need for deeper bond markets and greater SME access to credit. Regional financial integration, especially for bond markets, can create bigger, deeper and broader financial markets. 66 6 Concluding observations Developing Asia has an enviable record of rapid growth in the past. Fastest-growing region in the world Got many of the fundamentals “right” Rapid growth has contributed to massive poverty reduction The region has recovered well from global financial crisis but faces the challenge of sustaining long-run growth in the post-crisis period. Faces a less benign external environment as well as aging and other big shifts Region is still home to two-thirds of the world’s poor This growth has been the consequence of a sustained increase in productive capacity. Capital accumulation and TFP growth have both played a role. 67 5 Concluding observations Policies which delivered rapid sustained growth in yesteryear’s low-income, capital-scarce Asia will be less effective in today’s middle-income, capital abundant Asia. In particular, growth will increasingly have to come from improving TFP growth rather than factor accumulation. Evidence of this study shows that TFP growth is growing in relative importance as the driver of economic growth. Therefore, policies that promote TFP growth will hold the key to sustaining growth in the post-crisis period. In the context of promoting TFP growth, some key areas that merit the attention of policymakers include: Infrastructure Human capital Financial development Trade, including intra-regional trade 68