L01_PreReadingGrowth - Duke University`s Fuqua School of

advertisement

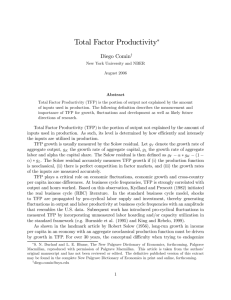

FUQINTR 389W Global Markets and Institutions Professor John Coleman Duke University Fuqua School of Business June 2010 Rethinking the Boundaries of Business School Course Outline • Growth and Institutions • Labor and Trade • International Capital Flows; Supply-Side Economics • Financial Crisis Growth and Institutions 2009 per-capita real (PPP) GDP for select countries Labor and Trade International Capital Flows Supply-Side Economics Financial Crisis Production and Long-Term Growth Sustained Growth and Country-Level Income Inequality are Modern Phenomena World-Wide Per-Capita GDP Most of the World is Poor The 21st Century may be the Century of Convergence 2007 population • 6.7 billion - World • 1.3 billion - China • 1.1 billion - India China and India represent 36 percent of the world’s population Many Poor Countries are Still Being Left Behind How does output increase? Key to our analysis of growth will be the production function Can boost output by increasing factor inputs or using inputs more efficiently Aggregate Production Function • Aggregate production function for the US: y = A k.3n.7 – – – – y = real output (income) k = physical stock of capital n = labor input per unit of time A = level of efficiency or total factor productivity (TFP) Calibrating the Aggregate Production Function The production function is motivated by this fact: • Labor income share is consistently 70% of national income • Capital income share is 30% of national income Labor Income Share of GDP Wn/Y 1.0 Employee Compensation 7.5% 9.9% 0.9 0.8 0.7 Proprietors' and Rental Income 9.2% 0.6 0.5 0.4 Corporate Profits (NIPA) 0.3 0.2 0.1 Distribution of National Income, 1994 Employee Compensation as Percentage of GNP 1959-1999 (very stable over time at 70%) 1999 1997 1995 1993 1991 1989 1987 1985 1983 1981 1979 1977 1975 1973 1971 1969 1967 1965 1963 0.0 1959 Net Interest 1961 73.4% US Production Function: Measurement 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 y k 4612 4725 4624 4810 5138 5330 5490 5648 5863 6060 6139 6079 6244 6384 6609 6743 6995 7270 7560 7862 4491 4655 4765 4849 5004 5189 5328 5445 5572 5708 5830 5892 5979 6094 6258 6473 6566 6716 6815 6917 n 99.3 100.4 99.5 100.8 105.0 107.2 109.6 112.4 115.0 117.3 117.3 116.9 117.6 119.3 123.1 124.9 126.7 129.6 131.5 133.5 A 14.80 14.89 14.56 14.93 15.35 15.53 15.62 15.69 15.92 16.11 16.11 16.04 16.34 16.44 16.52 16.52 16.80 17.16 17.59 18.01 %A y A k n 0.3 0.7 0.6 -2.2 2.5 2.8 1.1 0.6 0.4 1.5 1.2 1.2 -0.7 1.8 0.6 0.5 0.0 1.7 2.1 2.5 2.4 • y, k, measured in billions of 1992 dollars. • n measured in millions of workers. • A is computed by using the production function A y/k n 0.3 0.7 Output per worker • Labor productivity is output per worker y k A n n 0.3 • Living standard is determined by • A: efficiency (or TFP) • k/n: capital per worker International Differences in Output per Worker contribution from Source: Hall and Jones, QJE(1999) Output per Worker = (Capital per Worker contribution) X (TFP) Growth Accounting and Efficiency of the Economy • Growth-accounting equation: y A k n 0.3 0.7 y A k n • The labor contribution to growth: 0.7 * % growth of labor • Capital contribution to growth: 0.3 * % growth in capital Growth Accounting for the United States, 1948-2000 Recent Productivity in the US Does TFP growth explain convergence? TFP relative to the US Years Canada France Germany Italy Japan Korea United Kingdom 1947 0.812 1948 0.793 1949 0.800 1950 0.820 0.531 0.462 1951 0.804 0.521 0.493 1952 0.840 0.526 0.522 0.590 0.434 1953 0.841 0.552 0.531 0.615 0.443 1954 0.817 0.570 0.571 0.621 0.463 1955 0.832 0.567 0.609 0.641 0.482 1956 0.876 0.586 0.631 0.670 0.494 1957 0.859 0.601 0.652 0.674 0.507 1958 0.860 0.600 0.660 0.698 0.496 1959 0.841 0.606 0.681 0.705 0.505 1960 0.843 0.643 0.737 0.716 0.551 1961 0.838 0.654 0.748 0.740 0.601 1962 0.836 0.658 0.742 0.740 0.564 1963 0.846 0.667 0.740 0.730 0.588 1964 0.851 0.679 0.768 0.731 0.621 1965 0.859 0.685 0.785 0.762 0.613 1966 0.864 0.692 0.770 0.770 0.631 1967 0.859 0.713 0.752 0.801 0.658 1968 0.873 0.719 0.810 0.808 0.708 1969 0.868 0.757 0.869 0.851 0.740 1970 0.914 0.788 0.909 0.876 0.779 1971 0.916 0.789 0.900 0.830 0.768 1972 0.909 0.791 0.892 0.827 0.773 1973 0.907 0.806 0.906 0.849 0.772 Source: Productivity, Vol. 2, by Dale W. Jorgenson, MIT Press, 1995. 0.240 0.239 0.235 0.246 0.252 0.245 0.265 0.271 0.275 0.303 0.316 0.313 0.310 0.348 0.668 0.673 0.687 0.686 0.678 0.700 0.701 0.677 0.677 0.689 0.677 0.678 0.699 0.706 0.704 0.742 0.769 0.770 0.775 Growth Accounting is Everywhere TFP Convergence Assumption Level of TFP U.S TFP growth at constant 1.3% Developing country TFP Income per capita relative to the US (time) Why Care About TFP? • Sustained Growth not possible without TFP growth • Incentive to invest related to return to capital---this falls rapidly to zero without TFP growth • Without TFP growth income will stop growing MPK 0.3 * A k 0.7 0.7 n Soviet Union had no TFP growth—return to capital fell to zero Growth from 1,000,000 BC to now • Pre-Industrial Revolution stagnation in per-capita income • Industrial Revolution and TFP • Growing Income Inequality • 21st Century may be the Century of Convergence Lucas: The Industrial Revolution • Malthusian trap • Fixed vs. reproducible inputs • Demographic transition Understanding efficiency • Higher A implies that the economy is more efficient • More output can be produced with the same inputs (labor and capital) • What drives A? Innovation and TFP Growth Technology Adoption Rates Differ Dramatically Across Countries Learning by doing and TFP growth In New Economy same effect is achieved by using computers and other IT --- this also raises y/n. What determines TFP? Relationship between Income and Growth Open Countries Tend to Converge Open: (1) effective protection rates < 40%, (2) quotas on < 40% of imports, (3) no currency controls or currency black markets, (4) no export marketing board, and (5) not socialist. Rodrik: Institutions for High-Quality Growth • Which Institutions Matter? • property rights • regulatory institutions • macroeconomic stabilization • social insurance • conflict management • How Are “Good” Institutions Acquired? • accepting institutional diversity • two modes of acquiring institutions • participatory politics as a metainstitution The Colonial Origins of Institutions and Development • Life expectancy for European colonists differed greatly by region of colonization • Low mortality regions encouraged the development of governance that replicated home institutions (e.g., United States, Australia, and New Zealand) • High mortality regions encouraged the development of extractive states which set up repressive institutions to maximize the extraction of resources (e.g., Congo and Gold Coast) • Early development of institutions have persistent effects on today’s institutions Source: Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson, AER(2001) • But institutions can still change today Growth and Radical Institutional Change: The French Revolution Ancien Régime in France/Europe • Landed nobility imposed feudalism/serfdom, which tied peasants to land and restricted a free labor market (recall that the vast majority of labor was in agriculture) Growth under new regime Growth under old regime • Urban oligarchy controlled major occupations by guilds, significantly limiting competition and restricting adoption of new technology • Nobility and clergy were exempted from many taxes, and indeed imposed taxes of their own, and were subject to different laws and courts French Revolution of 1789 • Abolished feudalism • Abolished guilds and internal tariffs • Significant reduction of power of nobility and clergy Source: Acemoglu, Contoni, Johnson, and Robinson, “The Consequences of Radical Reform: The French Revolution,” 2009 • Declaration of equality before the law for all citizens French Revolution Expanded into parts of Europe • Toppled established regime in Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, and parts of Germany • New regimes persisted even after the French left The World Bank Created out of Bretton Woods in 1944 • Prior to 1980 focus on loans tied to specific projects in developing countries • Later focused on adjustment lending that were meant to encourage policies to promote overall growth and lower inflation • Some successes: Ghana, Mauritius What went wrong? • Debt relief created poor incentives • Poor performing countries received as much or more follow-on loans as other countries • WB/IMF gave 18 adjustment loans to Côte d'Ivoire, despite persistent budget deficits of 14 percent of GDP • WB/IMF gave 22 adjustment loans to Pakistan, despite persistent budget deficits of 7 percent of GDP • Adjustment lending to many corrupt governments: 46 adjustment loans to Congo, Bangladesh, Liberia, Haiti, Paraguay, Guyana, and Indonesia Source: Easterly, The Elusive Quest for Growth, 2002. Botswana: A Diamond in the Rough Case Discussion 1. This case concerns, in large part, the diamond industry in Botswana, including the institutional mechanisms for exploiting this natural resource. a. Before the development of the diamond industry, the chief forms of wealth were land and cattle. What were the institutional arrangements for ownership and management of these two forms of wealth? Were these arrangements formal or informal? b. Why were the formal and informal arrangements that were in place before the discovery of diamonds of such importance to decisions about how to manage the diamonds? 2. The wealth associated with diamonds brings its own benefits and problems. Identify the key problems posed by this source of wealth, and explain which of Botswana’s formal and informal institutions addressed those problems. 3. Is Botswana truly anomalous in Africa (as suggested by some observers; see page 2 of the case)? What would determine if Botswana’s model is replicable in other countries with similar mineral wealth? Charter Cities? Optional Topic from www.chartercities.org Charter cities offer a truly global win-win solution. These cities address global poverty by giving people the chance to escape from precarious and harmful subsistence agriculture or dangerous urban slums. Charter cities let people move to a place with rules that provide security, economic opportunity, and improved quality of life. Charter cities also give leaders more options for improving governance and investors more opportunities to finance socially beneficial infrastructure projects. All it takes to grow a charter city is an unoccupied piece of land and a charter. The human, material, and financial resources needed to build a new city will follow, attracted by the chance to work together under the good rules that the charter specifies. 20 min video at www.chartercities.org/resources Paul Romer